|

| Out of the Night [The Black Dark Murders] Robert O. Saber [pseud. Milton K. Ozaki] Toronto: Harlequin, 1954 |

Related posts:

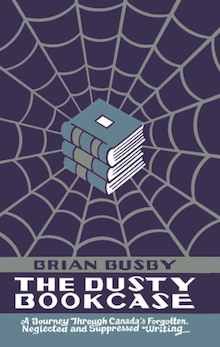

A JOURNEY THROUGH CANADA'S FORGOTTEN, NEGLECTED AND SUPPRESSED WRITING

|

| Out of the Night [The Black Dark Murders] Robert O. Saber [pseud. Milton K. Ozaki] Toronto: Harlequin, 1954 |

|

| 1989 |

|

| 1989 |

|

| 1991 |

|

| 1994 |

|

| Creature nel cervello [Brain Child] Milan: Mondadori, 1991 |

The weapons Britain is supplying to its Arab allies are somehow ending up in the hands of Eastern European fascists and the Foreign Office is not amused. One man, Gerald Burke, is called upon to put a stop to it. An Oxford-educated archeologist-turned-adventurer, Burke seems a good choice; he knows the region, has a good number of contacts, and hails from rural Nova Scotia (Chignecto, it is implied). What's more, Burke comes with Abdula el Zoghri, a manservant who has a talent for getting out of tight spots.

After accepting the assignment, our hero returns to his Bloomsbury Square flat to find a warning in the form of a black feather, quill-upwards, protruding from the brass plaque bearing his name. The fact that they're onto him doesn't deter Burke from his mission. Burke makes for Marseilles, and is booking passage to Salonika when a pretty Russian girl literally falls into his arms. He knows she's a spy, Zoghri knows she's a spy, and yet they're happy to play along.So begins my review of Black Feather, the lone novel by war hero and sometime pulp writer Harold Benge Atlee (1890-1978). You can read the entire piece here – gratis – at the Canadian Notes & Queries site.

Thankful for What?

Not for the mighty world, O Lord, tonight,

Nations and kingdoms in their fearful might —

Let me be glad the kettle gently sings,

Let me be thankful just for the little things.

Thankful for simple food and supper spread,

Thankful for shelter and a warm, clean bed,

For little joyful feet that gladly run

To welcome me when my day's work is done.

Thankful for friends who share my woe or mirth,

Glad for the warm, sweet fragrance of the earth,

For golden pools of sunlight on the floor,

For love that sheds its peace about my door.

For little friendly days that slip away,

With only meals and bed, and work and play,

A rocking-chair and kindly firelight —

For little things let me be glad tonight.

The Writers' ChapelAll are welcome!

St Jax Montréal

1439 St Catherine Street West

(Bishops Street entrance)

Tuesday, October 3rd at 6:00 pm

Under the comprehensive title of "Revenge," Robert Barr collects a score of the wildest flights of his imagination, which land us in all sorts of places. Horrors dire lie cheek by jowl with the broadest of farces. All tastes are suited save those the readers who wish to derive moral benefit from their literary pabulum, for there is not a scrap of moral to be extracted, although one can be invented to fit almost anywhere.The first American edition, with illustrations by Lancelot Speed, Stanley Wood, and G.G. Manton, is a thing of beauty. I wanted a copy for years, I searched for a copy for years, and in the end settled for this crummy print on demand thing from Dodo Press. I'm glad I did because Revenge! was not only this summer's favourite read, but it renewed my interest in its author.

In some natures there are no half-tones; nothing but raw primary colours. John Bodman was a man who was always at one extreme or the other. This probably would have mattered little had he not married a wife whose nature was an exact duplicate of his own.With all divorces one must pick a side. I chose to be with Mrs Bodman (she has no Christian name), but as the tale progressed she fell out of favour.

"It seems to me," he answered, not looking at her, "that it is rather late in the day for discussing that question."Mrs Bodman becomes increasingly agitated:

"I have much to regret," she said quaveringly. "Have you nothing?"

"No," he answered."

"Very well," replied his wife, with the usual hardness returning to her voice. "I was merely giving you a chance. Remember that."

Her husband looked at her suspiciously. "What do you mean?" he asked, "giving me a chance? I want no chance nor anything else from you. A man accepts nothing from one he hates. My feeling towards you is, I imagine, no secret to you. We are tied together, and you have done your best to make the bondage insupportable."

"Yes," she answered, with her eyes on the ground, "we are tied together, we are tied together!"

"Why do you walk about like a wild animal?" he cried. "Come here and sit down beside me, and be still." She faced him with a light he had never before seen in her eyes — a light of insanity and of hatred.Bloody hell! What an ending!

"I walk like a wild animal," she said, " because I am one. You spoke a moment ago of your hatred of me; but you are a man, and your hatred is nothing to mine. Bad as you are, much as you wish to break the bond which ties us together, there are still things which I know you would not stoop to. I know there is no thought of murder in your heart, but there is in mine. I will show you, John Bodman, how much I hate you."

The man nervously clutched the stone beside him, and gave a guilty start as she mentioned murder.

"Yes," she continued, "I have told all my friends in England that I believed you intended to murder me in Switzerland."

"Good God!" he cried. "How could you say such a thing?"

"I say it to show how much I hate you — how much I am prepared to give for revenge. I have warned the people at the hotel, and when we left two men followed us. The proprietor tried to persuade me not to accompany you. In a few moments those two men will come in sight of the Outlook. Tell them, if you think they will believe you, that it was an accident."

The mad woman tore from the front of her dress shreds of lace and scattered them around.

Bodman started up to his feet, crying, "What are you about?" But before he could move toward her she precipitated herself over the wall, and went shrieking and whirling down the awful abyss.