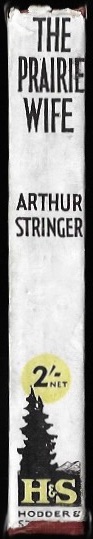

The Prairie Wife

Arthur Stringer

London: Hodder & Stoughton, [n.d]

251 pages

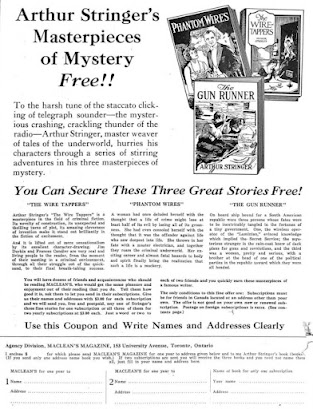

In the summer of 1985, I bought a copy of The Oxford Companion to Canadian Literature and read it from cover to cover. This is nowhere near as impressive as it might seem; what I read was the original two-column 843-page edition (1983), not the two-column 1099-page second edition (2001). Nevertheless, it was through the Companion that I first learned of Arthur Stringer. The author's entry, penned by Dick Harrison, amounts to little more than a half-page. Here are some of the things I learned:

- born 1874 in Chatham, Ontario;

- studied at the University of Toronto and Oxford;

- wrote for the Montreal Herald;

- established his literary career in New York;

- "made an enduring contribution to Canadian literature with his prairie trilogy: Prairie Wife (1915), Prairie Mother (1920), and Prairie Child (1921)."

Harrison gets the titles of the trilogy wrong –

The Prairie Wife,

The Prairie Mother, and

The Prairie Child are correct – but never mind, what stuck with me was

Prairie. As decades passed, I forgot all about Chatham, Toronto, Oxford, Montreal, and New York, and came to think of Stringer as a Western Canadian. It wasn't until 2009, when I read

The Woman Who Could Not Die (1929), my first Stringer, that I was reminded he was an Ontario boy. A Lost World novel set in the Canadian Arctic, I liked it well enough to keep reading and begin collecting his work.

|

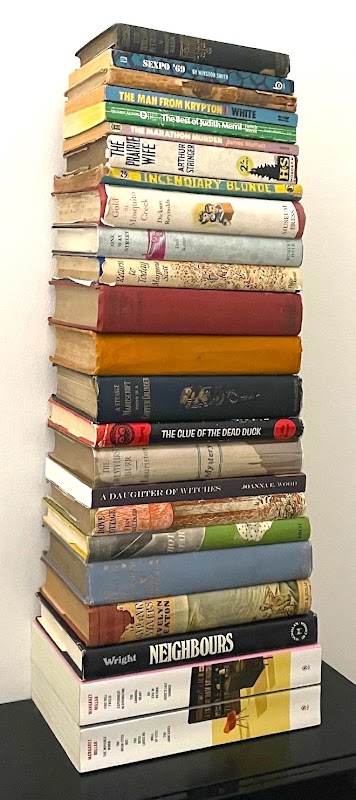

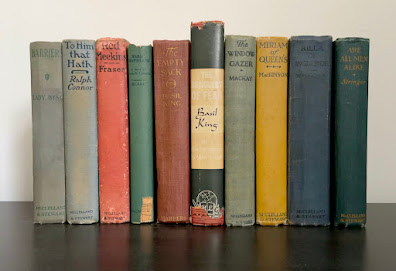

My Arthur Stringer collection (most of it, anyway).

Cliquez pour agrandir. |

Admittedly, much of my interest has to do with his enviable popularity, the deals he cut with Hollywood, and

his marriage to Jobyna Howland. This is not to suggest that I didn't like the books themselves. My favourite Canadian novel of the early twentieth-century is Stringer's

The Wine of Life (1921), which... um, was inspired by his marriage to Jobyna Howland.

A second admission: I put off reading The Prairie Wife, the first volume in Stringer's "enduring contribution to Canadian literature," for no other reason that it is set in rural Canada. Before you judge, I rush to add that this Montrealer has lived in rural Canada these past two decades. Country living attracts, but not novels set in the country. This may explain how it is that I was swept up by its early pages.

The Prairie Wife takes the form of a series of entries, written over the course of more than a year to someone named Matilda Anne. Its writer, Chaddie, begins by describing a voyage from Corfu to Palermo and then on to the Riviera. She is of the moneyed class – that is until Monte Carlo, where Chaddie receives a cable informing that the "Chilean revolution" has wiped out her nitrate mine concessions. Made a pauper, Chaddie's first action is to dismiss her maid; the second is to send word to her German aristocrat fiancé:

I sent a cable to Theobald Gustav (so condensed

that he thought it was code) and later on found

that he'd been sending flowers and chocolates all

the while to the Hotel de L'Athenee, the long boxes

duly piled up in tiers, like coffins at the morgue.

Then Theobald's aunt, the baroness, called on me,

in state. She came in that funny, old-fashioned,

shallow landau of hers, where she looked for all

the world like an oyster-on-the-half-shell, and spoke

so pointedly of the danger of international marriages that I felt sure she was trying to shoo me

away from my handsome and kingly Theobald

Gustav — which made me quite calmly and solemnly

tell her that I intended to take Theobald out of

under-secretaryships, which really belonged to Oppenheim romances, and put him in the shoe business in some nice New England town!

After a respectable period of mourning lost wealth, Theobald Gustav throws her over. Just as well, really, because the Paris Herald had reported on of a traffic accident that had occurred when he'd been in the company of a "spidery Russian stage-dancer." On the rebound, Chaddie proposes to Scots-Canadian Duncan Argyll McKail, whom she'd met in Banff the previous October. He is too much in love and far too practical to turn her down.

And so, this is how Chaddie, an American socialite who'd shared the company of Meredith and Stevenson, and had sat through many an opera at La Scala, ends up in a one-room shack with flattened tin can siding on the remote Canadian prairie.

Duncan – annoyingly, his bride refers to him as "Dinky-Dunk" – is a civil engineer from the east. He's got it in his mind to make a fortune through farming, and has purchased a 1700-acre parcel of land one hundred or so kilometres northwest of, I'm guessing, Swift Current.

"He kept saying it would be hard, for the first year or two, and there would be a terrible number of things I'd be sure to miss," Chaddie writes Matilda Anne.

No doubt!

Harrison doesn't use the term "Prairie Realism" in his Stringer entry, but I will; The Prairie Wife is a good fit with later novels by Frederick Philip Grove, Martha Ostenso, and Robert Stead. Can we agree that Prairie Realism was never terribly realistic? Though pre-Jazz Age, Stringer's story begins as a crazy Jazz Age adventure in which a carefree debutante marries a man she may or may not love. In her earliest pages to Matilda Anne, she writes:

O God, O God, if it should turn out that I don't, that I can't? But I'm going to! I know I'm going to! And there's one other

thing that I know, and when I remember it,

It sends a comfy warm wave through all my body:

Dinky-Dunk loves me. He's as mad as a hatter

about me. He deserves to be loved back. And I'm

going to love him back. That is a vow I herewith duly register. I'm going to love my Dinky-Dunk.

Chaddie continues:

But, oh, isn't it wonderful to wake love in a man, in a strong man? To be able to sweep him off, that way, on a tidal wave that leaves him rather white and shaky in the voice and trembly in the fingers, and seems to light a little luminous fire at the back of his eyeballs so that you can see the pupils glow, the same as an animal's when your motor head-lights hit them!

There's a clear separation between the opening pages and the rest of the novel. Whimsy gives way to practicality, as Duncan chases his fortune. Remarkably, Chaddie settles on the prairie, and into matrimony, rather nicely. Harrison writes of "disillusionment as the marriage deteriorates," but this reader saw nothing of the kind. True, there are moments of discord, as in the strongest of marriages, but Dinky-Dunk and Chaddie – he calls her "Gee-Gee" – are soon in one another's arms. She does come to love her Dinky-Dunk.

|

| The frontispiece of the A.L. Burt photoplay edition, c.1925. |

I don't know what Harrison means when he writes of Chaddie's "mature resolve as she begins an independent life on the Prairies." The married couple only become closer as the novel progresses, and the two are increasingly reliant on a slowly growing cast of characters. The earliest, hired man Olie, is a silent Swede who at first can't keep his eyes off Chaddie. This male gaze has nothing to do with objectification, rather her ridiculously impractical city dress. Pale Percival Benson Wodehouse, whom this reader suspects to be a

remittance man, is next to appear. He was sold the neighbouring ranch from "land chaps" in London. Nineteen-year-old Finnish Canadian Olga Sarristo enters driving a yoke of oxen. Two weeks earlier, what remained of her family had burned to death in their own shack one hundred or so miles to the north. To Chaddie, stoic and stunning Olga is like something out of Norse mythology, "a big blonde Valkyr suddenly introducing herself into your little earthly affairs." Olga is a welcome addition to the farm; every bit as capable physically as Olie and Duncan. Last to arrive is Terry Dillion, a fastidious young Irishman who had once served in far off lands with the British Army.

Together they support Duncan's big gamble, which involves putting all he has on a sea of wheat covering his 1700 acres. Threatened by draught, fire, and hail, the crop survives, making him a wealthy man. His riches are further increased by a new rail line to be built across his land. The final pages have Duncan and Chaddie poring over house-plans mailed from Philadelphia. "We're to have a telephone, as soon as the railway

gets through," she writes Matilda Anne.

The Prairie Wife is the first Stringer novel I've read with a woman narrator. Early pages aside, I found Chaddie's voice oddly convincing.

This audio recording by Jennifer Perree, stumbled upon in researching this novel, reinforced my conviction. An enjoyable story, an entertainment, it left me wanting to hear more from Chaddie.

And there is more!

Stringer wrote more than forty novels, but

The Prairie Mother is the only one to spawn a sequel,

The Prairie Mother (1920) – and then another in

The Prairie Child (1922).

Like Dinky-Dunk, Stringer really knew how to make a buck.

Favourite sentence:The trouble with Platonic love is that it's always turning out too nice to be Platonic, or too Platonic to be nice.

Bloomer:

I can't help thinking of Terry's attitude toward

Olga. He doesn't actively dislike her, but he

quietly ignores her, even more so than Olie does.

I've been wondering why neither of them has succumbed to such physical grandeur. Perhaps it's

because they're physical themselves.

Trivia: In 1925, The Prairie Mother was adapted to the silver screen. A lost film, the trade reviews I've read are lukewarm, mainly because there is no gunplay. Chaddie is played by comedic actress Dorothy Devore, one of many who fell in making the transition to talkies. New to me is Herbert Rawlinson, who played Duncan. Olga is played by Canadian Frances Primm, about whom little is known, A pre-Frankenstein Boris Karloff plays Diego, a character that does not feature in the novel. Most interetsing to the silent film buff is Gibson Gowland (Olie), the man who played McTeague in Erich von Stroheim's Greed.

|

| Motion Picture Magazine, December 1924 |

Object: My copy was purchased last year from a bookseller located in Winterton, Lincolnshire. Price: £9.00. Sadly, the jacket illustration is uncredited.

The rear pushes all three books in Stringer's trilogy, The Prairie Child not yet available in a bargain edition. The flaps feature a list of other Hodder & Stoughton titles, including works by Canadians Ralph Connor (The Sky Pilot of No Man's Land [sic]), Hulbert Footner (The Fugitive Sleuth, Two on the Trail), Frank L. Packard (The Night Operator, The Wire Devils, Pawned), Robert J.C. Stead (The Homesteaders), and Bertrand W. Sinclair (Poor Man's Rock).

Access: The Prairie Wife first appeared in 1915, published serially over four issues of the Saturday Evening Post (16 January - 6 February). That same year, it appeared in book form in Canada (McLeod & Allen) and the United States (Bobbs-Merril). Both publishers used the same jacket design:

Evidence suggests that The Prairie Wife is Stringer's biggest seller. A.L. Burt published at photoplay edition tied into the 1925 Metro-Goldwyn Mayer adaptation. Is that Boris Karloff as Diego on the right?

At some point, Burt went back to the well to draw

Prairie Stories, which included all three novels in Stringer's prairie trilogy. As far as I've been able to determine,

The Prairie Wife last saw print in

The Prairie Omnibus (Grosset & Dunlap, 1950), in which it is paired with

The Prairie Mother.

Used copies of

The Prairie Wife can be purchased online for as little as US$8.95.