The Untempered Wind

Joanna E. Wood

Ottawa: Tecumseh, 1994

354 pages

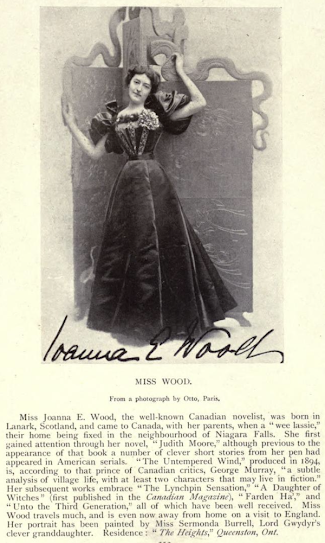

In Henry James Morgan's Types of Canadian Women, published in 1903 by William Briggs, Joanna E. Wood is described as a "well known Canadian novelist."

She is not today.

She was not a half-century ago.

She was not a century ago.

"Meteor-like" is the word Barbara Goddard uses to describe Wood's career. In fact, it ended the very year Types of Canadian Women appeared.

The novelist was all of thirty-five.

Joanna E Wood was twenty-six when The Untempered Wind, her first novel, was published. Its heroine, Myron Holder, has had a child out of wedlock; she is "a mother, but not a wife," and so suffers the scorn of Jamestown, the small Ontario village in which she was born and raised. Myron's own mother is dead, as is her father. Her unloving grandmother is very much alive and shares a modest house with Myron and her baby boy.

When first published in 1894, The Untempered Wind proved a critical and commercial success, encouraging three printings, each featuring the same ten illustrations. The frontispiece was used on the cover of the Tecumseh edition:

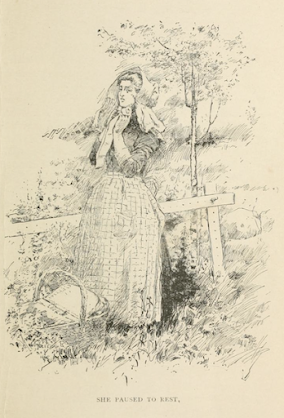

Had I been involved in its publication, I would have chosen one of the illustrations depicting Myron. This is my favourite:

Still, I understand the selection. Myron may be the protagonist of The Untempered Wind, but more pages are given over to those so quick to pass judgement. Mrs Deans, the most prominent, leverages her employ of Myron as an act of sacrifice and charity: "I feel a duty to have her here, but it goes ag'in me, Mr. Long [the ragman] it does that; but there, we all have our cross and we must help along as well as we can." Other women of the village visit Myron's grandmother on the pretence of providing sympathy. Each hopes to be the one who uncovers the identity of the child's father, but not even old Mrs Holder knows his name.

There was something hideously repulsive in this boy's secret cruelties, horrible to relate, sickening to contemplate. But the creatures he tormented, maimed, killed, knew neither anticipation nor remembrance; the "corporeal pang" was all.

The Jamestown people, in making a pariah of Myron Holder, were not urged to the step by imperative feeling of hurt honor or pained surprise. Such faults as hers were not uncommon there; but never before had the odium rested upon one only. Besides, there had always been some "goings on" and some "talk" indicative of the affair. In Myron Holder's case, the Jamestown people had been caught napping. In such eases a marriage and reinstatement into public favor was the usual sequel, arrived at after much exhilarating and spicy gossip, much enjoyable speculation, much meditation upon the part of the matrons, and much congratulation that all had ended so well.

The Untempered Wind was first published the year before The Woman Who Did by fellow Upper Canadian Grant Allen. The latter, also a story of an unwed mother, was a succès de scandale. Wood's novel didn't raise as much stink, but it was a success. The three printings by original publisher New York's J Slewing Tait and Sons were followed in 1898 by an Ontario Publishing Company edition.

Together The Untempered Wind and The Woman Who Did stand as two of the most remarkable Canadian novels of the nineteenth century.

Neither was so much as mentioned in my CanLit classes.

Object and Access: A trade paperback with introduction by Klay Dyer, The Untempered Wind is the seventh volume in Tecumseh's essential Early Canadian Women Writers Series. I purchased my less than pristine copy eight years ago at London's Attic Books. Price: $2.23. It's available from the publisher at $17.95 (plus postage) through this link.

|

| Current Literature, November 1894 |

The Tait and Sons first edition can be read online here, but this scan of the third printing – reproduced in the Tecumseh edition – is much easier on the eyes.