What a year! On day two, while returning from a grocery run in nearby Brockville, I stopped at a thrift store and found first editions of Gilbert Parker's The Judgement House and Pardon My Parka by Joan Walker. They set me back all of four dollars.

The Judgement House had been on my radar only two months, but I'd been looking for Pardon My Parka well before my 2022 tear through Walker's East of Temple Bar, Murder By Accident, Repent at Leisure, and the condensed Repent at Leisure. It completes my collection of her works.

I arrived home from Brockville to find this gift from my friend James Calhoun my mailbox:

More on that below.

The strangest book buying experience occurred during a May visit from our daughter. She'd just moved to her first flat and was looking for inexpensive pots and pans, so the family set out for a favourite thrift store in Smiths Falls. During the drive I began talking about Jan Hilliard whose novel Miranda I'd set down to make the trip. I went on about her background, her rascal of a father, her art school education, what a good writer she was, and how unfair it is that she's so forgotten. When we got to the store, mother and daughter went off hunting kitchenware. I made for the books, where I found – within seconds – a first edition of Hilliard's The Salt-Box. I'd never before seen any of her books in a store. The copy doesn't have a dust jacket and is a library discard, but at 66 cents I shan't complain. It completes my collection of her works.

That Judgement House, Pardon My Parka, and The Salt-Box didn't make this year's list gives some idea as to how good 2024 was in terms of book purchases.

This years top ten were bought from booksellers in Canada, Austria, England, Scotland, and the United States:

"A chilling mystery with a James Bond-Simon Templar flavour, and devilish spoof on Canadian politicians," says the cover copy.

We'll see.

Set around Expo '67, this was purchased after reading the disappointing So Long at the Fair.

An 1895 novel written in response to Grant Allen's scandalous The Woman Who Did. I like Allen's novel, but understand that Victoria Cross was highly critical.

I'm ready to hear her out.

This one is a murder mystery set amongst well-paid people working in Toronto's lucrative magazine industry. Different times. I grew jealous.

When I found this Gibbon book – signed – I leapt.

A novel that would've appealed as a very young man. Don't know why I didn't buy it then, but I have it now... and in a photoplay edition!

It says everything about my reaction that I bought two other Glyns after reading it.

Toronto: Nelson, Foster &

It's difficult to pace oneself with Jan Hilliard; she wrote only five novels. I'm saving A View of the Town, the only one I've not read, for next year. Seventy-year-old reviews suggest it is her funniest. By now, I feel I know Hilliard; much of that humour will be black.

My favourite read of 2024!

And more than one!

Duncan Campbell Scott

Toronto: Ryerson, 1945

This year saw a good many gifts to the Dusty Bookcase, beginning with the book that arrived on the second day in January:

Raymond Souster's third book and first novel, the poet drew something from his wartime experience in the writing, but it is no way autobiographical.

Thank God.

A gift from James Calhoun.

Peter Donovan

Toronto: Macmillan, 1930

A novel set in the Toronto art world by a Montrealer better known as "P O'D." Robertson Davies was an admirer, describing Donovan as "knowingly and intentionally and pointedly funny."

Another gift from James Calhoun, this is sure to be read in 2025.

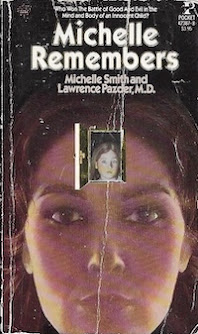

Michelle Smith and

Lawrence Pazder

New York: Pocket, 1981

After I'd expressed frustration in being unable to find an affordable copy copy of this Satanic Panic classic, Brad Middleton of My Bloody Obsession sent two copies my way. This one is a first printing of the July 1981 first Pocket books edition.

A tragic love story.

Finally, I received two large boxes of books from the West Coast sent by my friend Karyn Huenemann containing books by L. Adams Beck, Frances Brooke, Ralph Connor, Muriel Denison, Norman Duncan, Sara Jeanette Duncan, Muriel Elwood, F.T. Flahiff, Grey Owl, Nellie McClung, Frederick Niven, Frank L. Packard, George L. Parker, Gilbert Parker, Charles G.D. Roberts, and Duncan Campbell Scott.

Again, what a year!

.jpg)