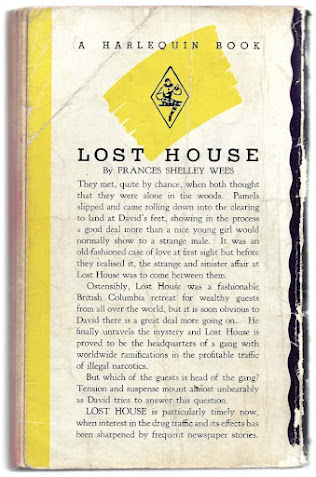

Lost House

Frances Shelley Wees

Winnipeg: Harlequin, 1949

192 pages

So, Lost House? Hot or cold?

The prologue is frozen solid. This takes the form of a brief conversation between the head of Scotland Yard's Criminal Investigations Department and one of his detectives. Apparently, a man known as "the Angel" is up to something in a place known as "Lost House." The detective is dispatched to see what's what:

He rose. "Very well, sir, I'll have a go at it."

Action shifts to British Columbia, where newly-minted physician David Ayelsworth is exploring "the forest primeval" astride his horse Delilah. What David finds is a half-submerged body by the shore of a lake. The doctor's attention is then drawn to the sound of a young woman chasing a dog. She falls, twists her ankle, and he comes to her aid. The injured young woman is Pamela Leighton, who lives at nearby Lost House.

Harlequin's cover reminds me of nothing so much as Garnett Weston's Legacy of Fear (New York: W S Mill/William Morrow, 1950), which also features a grand house in a remote corner British Columbia.

Interesting to note, I think, that both pre-date Psycho.

The mysterious D. Rickard is credited with Harlequin's cover art. I make a thing of his rendition because Rickard's Lost House isn't at all as described in the novel. Wees's Lost House rests on a walled island linked to the mainland by causeway and drawbridge. An immense structure, an exact replica of an

English country manor, it was built by an eccentric Englishman who sought to further his wealth through a local silver mine. The mine proved a dud, the Englishman died, and all was inherited by Pamela Leighton's mother. Improbably, Mrs Leighton manages to maintain the estate by taking in paying guests during the summer months. This year, they include:- James Herrod Payne, novelist;

- Shane Meredith, tenor;

- Archdeacon Branscombe, archdeacon;

- Lord Geoffrey Revel, lord.

There's a fifth male guest, an unknown who is being cared for by Mayhew, the resident doctor. The patient was brought in one night after having taken ill on a train stopped at Dark Forest, the closest community.

(That Lost House has an infirmary speaks to its immensity. That Lost House staff and guests are close in number speaks to Mrs Leighton's financial difficulties.)

There are also four female guests, Lord Geoffrey's mother being one, but it's the males that command our scrutiny; after all, we know the Angel to be a man.

Which is the Angel? Which is the Scotland Yard detective? It's impossible to tell. The focus is so much on David and Pamela, and to a lesser extent Mrs Leighton and Dr Mayhew, that the guests are little more than ghosts. The reader encounters them from time to time, but as characters they barely exist. Lost House fails as a mystery for the simple reason that Wees provides no clues. The Angel could be any one of the male guests. Indeed – and here I spoil things – much of the drama in the climax comes when he passes himself off as the Scotland Yard detective. And why not? There's nothing that might lead the reader or the other characters to suspect otherwise.

As the novel approaches mid-point, Pamela apologies to David. "I've dragged you into a dreadful mess," she says. "I've spoiled your holiday..."

This isn't true; David's involvement has nothing to do with her. He's at Lost House because the body he found by the lake turns out to be that of a missing Lost House staff member.

Lost House is a dreadful mess. The novel's disorder may have something to do with the fact that it first appeared serialized in Argosy (Aug 27 - Oct 1, 1938). Its fabric is woven with several threads that are subsequently dropped, the most intriguing involving Verve. A new brand of cigarette. Verve is a frequent topic of conversation, as in this early exchange between Pamela and David:

"You've been smoking a tremendous lot." Her eyes were on the big ash tray before her.

"Yes."

"I like Verves," she decided, looking at the tray. "Not as much as you do, apparently... I don't smoke very much though. But when one is a bit tired, a Verve seems to give one exhilaration. Doesn't it?"

"Yes," David said after a moment, "I... think it does."

"You say that very strangely."

"Do I ?" He shifted in his chair. "perhaps I'm a little lightheaded. I've sat here and smoked twenty of them in a row, and they do give one exhilaration. That's... the way they're advertised, of course. But other cigarettes, other things, have been advertised that way, too. Only... this time... and the whole world is smoking Verves. They've caught on extremely well. The whole world."

She said, troubled, "You are queer."

"Sorry." He crushed out the cigarette carefully and locked his hands together.

More follows, including a suggestion that the cigarettes have some sort of additive, but the subject is dropped in the first half of the novel. In the latter half, it's revealed that the Angel is using Lost House to store marijuana bound for the United States and United Kingdom. It seems a very lucrative trade. Might the drug have something to with Verve? The question is asked, but never answered.

Lost House was the second ever Harlequin, but the publishers pushed it like old pros.

Dope? Sure.

Danger? Ditto.

Dolls? Well, Pamela is described as attractive in the way prospective a mother-in-law might approve. Wees makes something of her playing around with "the soft pink ruffles of her skirt" when speaking to David in the final chapter. That's sexy, I guess. But Pamela's just one doll. The female guests at Lost House include a sad middle-aged widow who has yet to throw off her weeds, elderly Lady Riley, and two older spinster sister twins who live for knitting.

Pamela's mother often appears in a lacy negligee, though only before her daughter. Is Mrs Leighton the the other doll?

Back cover copy continues the hard sell:

Pamela does not "land at David's feet, showing more in the process than a nice girl would normally show to a strange male." She wears a heavy skirt that approaches the length of a nun's habit. I add that she has sensible walking shoes.

Lost House is not "a fashionable British Columbia retreat for wealthy guests from all over the world;" it is nowhere so exotic, attracting only the dullest the English have to offer.

At end of it all, I found Lost House neither hot nor cold. It's lukewarm at best, despite Mrs Leighton's negligees.

*In fairness, as a romance novel, No Pattern for Life doesn't fit the Ricochet series. I recommend it as a strange romance.

Trivia I: In the preface to the anthology Investigating Women: Female Detectives by Canadian Writers (Toronto: Dundurn, 1995), David Skene-Melvin writes that the novel's royalties helped finance "Lost House," Wees's home in Stouffville, Ontario.

Trivia II: Like Wees, David is a graduate of the University of Alberta. He and his father practice medicine at the University Hospital, Edmonton.

|

University Hospital, Edmonton, Alberta, c. 1938

|

Object: A very early Harlequin, my copy is a fragile thing. The publisher used the same cover in 1954 when reissuing Lost House as book #245, marking the last time the novel saw print.

Access: Lost House was first published as a book in 1938 by Philadelphia's Macrae-Smith. The following year, Hurst & Blackett published the only UK edition. In 1940, the novel appeared as a Philadelphia Record supplement.

As of this writing, one jacketless copy of the Macrae-Smith edition is being offered online. Price: US$50.00. I'm not sure it's worth it, but do note that the image provided by the bookseller features boards with yellow writing. I believe orange/red (above) to be more common.

The Whitchurch-Stouffville Public Library doesn't hold a single edition of Frances Shelley Wees's twenty-four books.