Morgan's Castle

Jan Hilliard [Hilda Kay Grant]

New York: Abelard & Schulman, 1964

188 pages

An uncredited dust jacket of mysterious design, whatever does it mean? The rear image provides no clue.

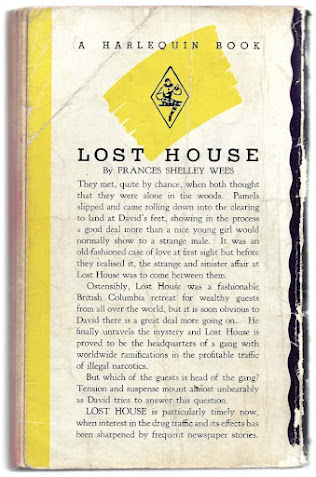

The covers of Jan Hilliard's other novels are much more straight-forward. Consider this:

A View of the Town, is "A NOVEL OF SMALL TOWN LIFE IN NOVA SCOTIA," as are most of her novels. Morgan's Castle stands with The Jameson Girls and Dove Cottage as one of three set outside her home province. The Jameson Girls and Dove Cottage are darker than her Nova Scotia novels, while Morgan's Castle is the darkest by far. This is not to suggest that the humour, which runs through all her fiction, is entirely black.

Jan Hilliard's career as a novelist lasted just ten years. One wonders why it wasn't longer. Her novels garnered nearly uniformly positive reviews – I've yet to find an exception – yet Morgan's Castle is the only one to have been reissued in paperback. "A spellbinding novel of romance and suspense in the Du Maurier [sic] tradition," the tagline reads. I was reminded more of Muriel Spark and Margaret Millar, but this may be because I'm more familiar with their respective works.

Aunt Amy has sent Laura money for a train ticket to the town of Greenwood, where she lives and breeds spaniels. There is a husband, Uncle James, but he is as irrelevant to the story as he is to Aunt Amy. The focus of her life is Charlotte Morgan, depicted here by Reint de Jonge on the cover of the Dutch translation, Spel met de dood (Haarlem: Staarnestad, 1966).

Charlotte may just be the most beautiful, most refined, most elegant woman in Greenwood; that she is the wealthiest is not up for debate. The widow of Robert Morgan, heir to a vast Niagara winery, she lives with her twenty-eight-year-old son Robbie and various servants at Hilltop House, known to the locals as "Morgan's Castle." It is located on a bluff above and away from the town and is described as looking something like a castle, though the artist for the Ace edition imagines it as a large Anglican church.

Aunt Amy sent her niece train fare on the pretence of wanting to give the girl a birthday party. Laura's four brothers and their wives will be there, but not the patriarch. Amy is well aware that Sidney won't be able to afford a ticket.

Because she's turning sixteen, Laura's siblings are concerned about shouldering the cost of further education. Is it not enough that their wives provide her with their castoffs? Sure, those old dresses have frayed hems and missing buttons, but Laura knows knows how to sew. They need not worry. Aunt Amy has a plan – and it has nothing to do with tuition.

Aunt Amy sent her niece train fare on the pretence of wanting to give the girl a birthday party. Laura's four brothers and their wives will be there, but not the patriarch. Amy is well aware that Sidney won't be able to afford a ticket.

Because she's turning sixteen, Laura's siblings are concerned about shouldering the cost of further education. Is it not enough that their wives provide her with their castoffs? Sure, those old dresses have frayed hems and missing buttons, but Laura knows knows how to sew. They need not worry. Aunt Amy has a plan – and it has nothing to do with tuition.

Over the past year, Charlotte has taken a shining to the girl. Once so skinny and boyish, Laura is becoming a woman. This, um, development hasn't escaped Aunt Amy's attention either. She criticizes her niece's white dress as being too revealing, even though it's an old thing that once belonged to a brother's wife.

Aunt Amy's attraction to Charlotte is nuanced while Charlotte's attraction to Laura is simple. She would like the girl to marry her son Robbie, produce offspring, and secure the line of succession in the family business. Never mind the age difference, the time is right. It's almost as if the fates had brought them together. Just a few months ago, not long after Laura's last visit to Greenwood, Robbie's childless wife Phyllis died suddenly after having sprinkled arsenic, which she thought was sugar, on a bowl of strawberries.

Aunt Amy's attraction to Charlotte is nuanced while Charlotte's attraction to Laura is simple. She would like the girl to marry her son Robbie, produce offspring, and secure the line of succession in the family business. Never mind the age difference, the time is right. It's almost as if the fates had brought them together. Just a few months ago, not long after Laura's last visit to Greenwood, Robbie's childless wife Phyllis died suddenly after having sprinkled arsenic, which she thought was sugar, on a bowl of strawberries.

She is not.

Laura has a handle on her ne'er-do-well father, but is nowhere near so savvy or keen-eyed when it comes to others. There's no surprise here. Despite having had to deal with Sidney's fabrication and deceit, her innocence is such that she believes these traits are unique to Sidney.

Morgan's Castle is in no way a detective novel, nor is it a mystery novel, though there are two murders (and many more in the backstory). The first murderer is obvious. The second murderer is a little less so, though one anticipates the act.

Could be.

Object: Yellow boards in an uncredited dust jacket. I've mentioned the uncredited bit before, I know, but it is relevant here because Hilliard, who worked for Abelard-Schulman, provided her own covers. The only one I have seen credited is Dove Cottage, which features this illustration by son of Scotland William McLaren:

Access: As with the author's four other novels, the first edition of Morgan's Castle enjoyed one lone printing. What sets it apart is a mass market paperback published three years later by Ace featured above, making it the biggest selling of the author's nine books.

The Toronto Star Weekly published Morgan's Castle in two parts over two issues (July 11-18, 1964). I've consulted various pals about the Ace cover, but have no definitive answer as to who should be credited with the illustration. What I can say is that it is accurate in its depiction of Laura.

As I write, two copies of the Abelard-Schulman edition are being offered online. Both ex-library copies, they're listed at US$5.06 and US$64.67. Take your pick. Two copies of the Ace edition are also listed. The cheaper, at US$7.12, has a cocked spine. The other, which "can have notes/highlighting," is being sold by Thrift Books for US$50.06.

The less said about Thrift Books the better.

Spaarnestad's aforementioned Spel met de dood was republished at some point. Judging by the dress, I'm guessing the second appeared in the 'seventies.