The Money Master;

Being the Curious History of Jean Jacques Barbille,

His Labours, His Loves and His Ladies

Gilbert Parker

Toronto: Copp Clark, 1915

360 pages

I bought my first Gilbert Parker book at a library sale in the mid-eighties. By 1990, it was gone, though I have no idea where. My fault, of course. I'd paid it little attention because Parker himself wasn't paid much attention. His name had never once come up in university courses. The Oxford Companion to Canadian Literature, then my bible, doesn't accord the man so much as one of its 1199 pages, despite popularity and critical acclaim (both now a century past).

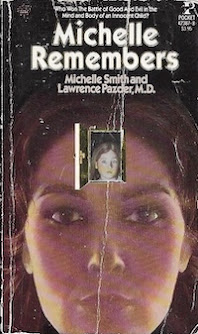

I couldn't even remember which Parker I'd owned back then. What I did remember was an illustration and caption depicting a miserable man traveling to Quebec in the company of a beautiful woman who seemed intent on marriage. Imagine my surprise when in researching this recent read I came upon:

The image of the reluctant groom threw me because Parker depicts him as being extremely keen on marrying the woman in the funnel.

The fiancé, Jean Jacques Barbille, is heir to a fortune built over four generations. Having transformed these inherited riches into slightly greater riches, the Canadien has an idea to visit the land of his ancestors, where he expects to be recognized as a man of great importance. Paris disappoints, but folks in the nether regions appreciate his money and so accord deference. Satisfied, Jean Jacques sets off for home with purse depleted, comforted by the knowledge that his various endeavors, save one or two, are moderately successful.

Whilst crossing the Atlantic aboard the good ship

Antoine, Jean Jacques encounters Spanish Amazon Carmen Delores – she of the funnel – and Sebastian Delores, her father. They are on the run because papa – the sinister figure at the funnel's base – had been on the losing side of Spain's most recent power struggle. If anything, young Carmen suffered a far greater loss in that her lover Carvillho Gonzales was executed for his efforts:

Carmen had made up her mind from the first to

marry Jean Jacques, and she deported herself accordingly – with modesty, circumspection and skill.

It would be the easiest way out of all their difficulties. Since her heart, such as it was, fluttered,

a mournful ghost, over the Place d’Armes, where her

Gonzales was shot, it might better go to Jean Jacques

than anyone else; for he was a man of parts, of

money, and of looks, and she loved these all; and

to her credit she loved his looks better than all the

rest.

In short, Jean Jacques looks a lot like Carvillho Gonzales.

The Money Master is the twentieth book I've reviewed here this year. It follows James De Mille's

The Cross and the Lily (1874) and Grant Allen's

The Great Taboo (1890) in being the third to feature a shipwreck. Parker's takes place when the

Antoine strikes an iceberg off the shore of Gaspé. Jean Jacques sees Carmen safely bestowed on a lifeboat, before giving up his spot to a crying fifteen-year-old boy. This he does, despite being not that strong a swimmer.

Fortunately, the Spanish Amazon

is a strong swimmer. When her lifeboat overturns, she makes for a floating chair, and then uses that chair to save Jean Jacques from drowning.

James Cameron take note.

Jean Jacques and Carmen marry in the Gaspé, much to the disapproval of the gentle townspeople of St Saviour:

It was bad enough to marry the Spanische, but to

marry outside one’s own parish, and so deprive that

parish and its young people of the week’s gaiety,

which a wedding and the consequent procession and

tour through the parish brings, was little less than

treason.

But what a story! The romance of it all is so great as to encourage the curious to travel as much as forty miles to catch a glimpse of the couple during Sunday mass. Carmen never corrects the presumption that she was saved by Jean Jacques and not the reverse.

Jean Jacques Barbille is a man with "a good many irons in the fire." Given the opportunity, he'll sell you insurance and lightning rods. His inherited riches grow not by leaps and bounds, rather by unsteady steps as taken by a toddler.

He fancies himself first and foremost a

philosophe. Though he never quite articulates his philosophy, Jean Jacques is quick to share that he spent a year at Université Laval. He carries with him a small volume titled

Mediations on Philosophy, which he bought in Quebec before sailing for France.

Jean Jacques is an egotist and something of a dandy, all the while being a good man. He is kind, treats his workers well, forgives debts, and is generous toward the less fortunate. The man's greatest fault relates to the home. He is so taken with his reputation and many business concerns that Carmen feels neglected; this in turn results in the most interesting scenes I've read in an old novel this year...

And, you know, I've read twenty.

Carmen does not feature in the scene, though she does in the next, which is easily the second most interesting scene.

Reading

The Money Master forty or so years after having first purchased a copy, I'm at a loss to explain how it is Gilbert Parker is so ignored.

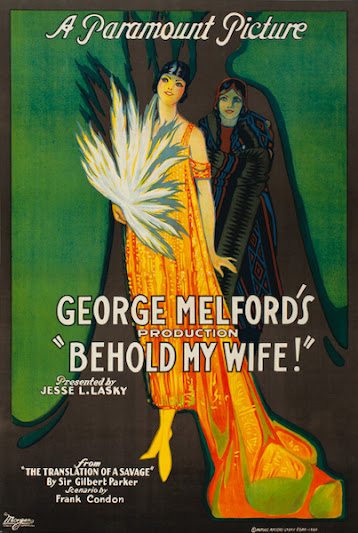

Trivia: Adapted to the Hollywood screen in 1921 as

A Wise Fool, the subject of the next week's post.

Object: The first Canadian edition, it features seven illustrations by French artist

André Castaigne, best known for having illustrated the first edition of

Le Fantôme de l'Opéra. 'Tis a thing of beauty, purchased ten or so years ago in London, Ontario. Price: $2.50.

I'm also the proud owner of the Hutchinson's UK first edition, which I picked up in

fin du millénaire Montreal for 30¢.

Sadly, it lacks its dust jacket (see below).

Access: The novel first appeared serialized in Hearst's Magazine (Aug 1913 - April 1914) and Nash's Magazine (Nov 1913 - Jul 1914).

As I write this, a Riverview, New Brunswick bookseller is offering a Very Good copy of the Copp Clark first edition at two dollars. There's no mention of a dust jacket, so I'm assuming that the bookseller believed it had none. Further west, a bookseller in Whitby, Ontario has a Canadian first

with dust jacket!

The asking price is $100.

If you don't have the cash, consider the two dollar copy. It's a steal, particularly if you live nearby and can avoid shipping charges.

Before making your decision, consider Harper's American first with its unusual wrap-around jacket illustration, drawn from one of Castaigne's interior illustrations.

A bookseller in Portland, Oregon is offering this copy at US$35:

At the high end – US$350 – we have the Hutchinson UK first on offer from Babylon Revisited, a favourite bookseller. Must say that the cover illustration pales somewhat when compared to the work of Monsieur Castaigne.

Buyer beware, none of Castaigne's illustrations feature in the Hutchinson.

As always, print on demand copies are not to be considered.

Woodrow Wilson would agree.

Related post: