Eyes of a Gypsy

John Murray Gibbon

Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1926

255 pages

This past Saturday marked the sesquicentennial of John Murray Gibbon's birth. That this aging Canadian Studies and English Literature graduate first learned of him only ten years ago seems absurd. For goodness sake, the man coined the term "Canadian Mosaic."

Two years have passed since I first read Gibbon's third novel,

Pagan Love, which I've described as

the most remarkable, unconventional, and challenging Canadian novel of the 'twenties.

Eyes of a Gypsy was Gibbon's fourth novel. Could it possibly live up to expectation?

I was won over in the early pages set on the good ship Alaric. Twenty-two-year-old Maurice Arden is our hero. An artist, he comes from a long line of commercial printers who have for generations scraped by in supplying cards, pamphlets, posters, and packaging for other businesses in and around Manhattan. As his father's only son, Maurice is set to inherit the struggle, and could not be more unhappy at the prospect.

The recent discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb having made Egypt all the rage, Maurice had left Manhattan – and fiancée Gladys in boozy Greenwich Village jazz clubs – for the ancient, dry Valley of the King. There he'd been inspired to create works that should prove profitable. Who knows, one might be used on the cover of a chocolate box.

And now Maurice is on his way home.

The Alaric isn't a grand liner, but it's what the family firm can afford. All glamour and elegance is supplied by fellow passenger Jacqueline Stuart, an uncommonly beautiful woman of Scots/Romani heritage, always "two steps ahead of Vogue," who appears each evening at the Captain's Table. Maurice learns the captain is a cousin, which explains her passage on so modest a vessel.

Last year's twenty-four Dusty Bookcase reads included one, two, three, four novels in which maritime accidents feature, so it came as no surprise that the Alaric strikes the hull of an overturned ship and begins to take on water.

Of the five maritime disasters, the sinking of the Alaric is the least catastrophic. No one dies. No one is hurt. No one gets wet. More anxious for his paintings than he is his soul, Maurice sets foot in the last lifeboat. At the moment it is about to be is lowered, he is joined by Jacqueline:

"What the hell! thundered the officer. "How wasn't she sent off with the first boats?"

"My fault entirely," explained the lady with dazzling teeth and an accent surprisingly Scotch. "I do hate to be hurried. This 'women and children first' business can be overdone. Doesn't give us a chance to ready for this world or the next."

Their bob on the ocean is not long – they are soon rescued by the passing Belladonna – but it is long enough for Maurice to become smitten. And who can blame him. The banter they exchange reveals Jacqueline to be witty, confident, clever, and full of life. Her reasons for visiting the Old World had nothing to do with Egyptomania, rather a scandal involving a United States senator. What happened exactly is uncertain – the novel offers three differing accounts – though all rely on the glamazon's talent as a fortune teller to New York's high society.

Two ships that might otherwise have passed in the night, the Alaric and Belladonna have passengers who know one another. It's a small world after all. In Jacqueline's case, it's the senator. For Maurice, it's his friend Kenneth MacLean, an architect from the Canadian west who is traveling with his sister Peggie, herself a painter.

Eyes of a Gypsy seems a simple novel, but isn't. The introduction of Peggie (page 28) suggests formula. Blonde, pretty, wholesome, innocent, she stands in stark contrast with the dark, beautiful, sophisticated, worldly-wise Jacqueline. Skipping ahead seventy-two pages, we get this:

The Scots-Canadian girl brought nature, the beloved mother. Jacqueline filled his dreams with more tempestuous emotions.

And so, a love triangle.

Yes, a triangle, because Gladys is no longer in the picture. After the Belladonna docks, Maurice is told that his father has just died, and is handed what may be the greatest "Dear John" letter in all of Canadian literature:

This reader began settling in. I've read enough novels with love triangles to know that resolution typically occurs in the penultimate chapter.

I should have known better.

Eyes of a Gypsy does not follow a conventional path because these are not conventional characters. Moreover, Gibbon is not a conventional writer.

Time, events, relationships, and scenes move quickly in this novel.

In short weeks, Maurice manages to turn the family firm around. Peggie and Kenneth make a brief visit to friends in Montreal, return to New York, rent a studio, but are soon off to their parents' home in the Kootenays. Jacqueline follows, because her Romani blood is drawn to great expanses, but also to because the senator threatens. This leaves Maurice all alone, until Peggie invites him to visit.

|

| Montreal, 1926 |

Once in Canada, the novel slows considerably. Plot and personages give way to loving descriptions of settings, the first being Montreal, the city in which the author spent most of his working life. The descriptions of the Kootenays, more lengthy, are accompanied by digressions on folk music, folk tales, trail riding, and First Nations culture.

It is a book the can be divided neatly in two. The first fourteen chapters have something in common with Pagan Love in that they deal with art, commerce, advertising, influence, and polished sophistication, but breaks in the last twelve which focus on the relatively simple lives and lore of those who rely on the land. That I prefer the first part says something about me. Both say much about Gibbon life – read Daniel R. Meister's Canadian Encyclopedia entry and see!

Two months ago, I won a copy of the author's first book Hearts and Faces (New York: Lane, 1916) at auction. It's set in the Bohemian Paris in which he'd studied art. I look forward to reading it and perhaps getting to know a bit more about the man, but am I wrong in wanting more about Gladys?

Favourite line: Early in the novel, a catty passenger on the Alaric says this of Jacqueline.

"If she can show us as much of the future as she does of her back, she is a wonder all right."

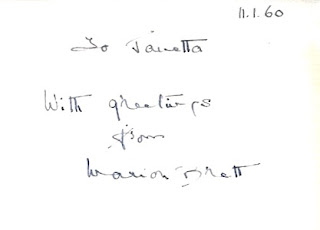

Dedication:

By great coincidence, my wife owns a copy of Ethel Watts Mumford's Hand-Reading Today: A New Angle of an Ancient Science (New York: Stokes, 1925), which she bought after reading Diana Souhami's The Trials of Radcliffe Hall (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1997). The latter is one of the best literary biographies I have ever read.

|

| New Broadway Magazine (June 1908) |

Object and Access: An orange hardcover, typical of its time, I purchased my copy in 2023 from an Ontario bookseller. Price: $21.00. Sadly, it lacks the dust jacket (which I've never seen).

As I write this, just one copy, also jacket-less, is listed for sale online. Price: $66.00.

Get it while you can.

Related post: