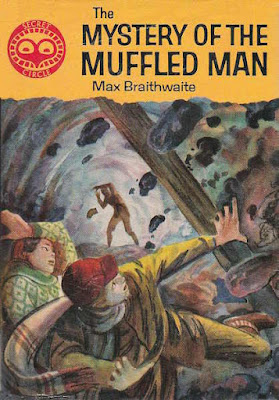

The Mystery of the Muffled Man

Max Braithwaite

Toronto: Little, Brown, 1962

160 pages

Fifty-five years ago, The Mystery of the Muffled Man vied with Joe Holliday's Dale of the Mounted in Hong Kong as a Christmas gift for young, bookish nephews. I doubt either won, but it would not surprise

me if the former achieved greater sales. After thirteen volumes, Holliday's Dale of the Mounted books were getting tired; I think it worth noting that the Hong Kong adventure would be his last. Braithwaite's, on the other hand, was part of the Secret Circle, a new and exciting series driven by a survey of booksellers, librarians, teachers and, most importantly, Scarborough school children and their parents.

Results in hand, General Editor Arthur Hammond, set about recruiting what was described in a November 1962 press release as "the best available Canadian authors."

It seems that most were too busy.

a northern Ontario mining town. Young Chris Summerville has been sent by his parents to meet his cousin, equally-young Carol Fitzpatrick, who will be visiting while her parents spend the Christmas holidays in Bermuda. Eventually, the train arrives, but before Chris meets Carol there is an altercation that will hang over the remainder of the novel. Chris's overly-friendly dog, Arthur, runs to greet the new arrivals, only to be clubbed by a "muffled man" who had emerged from the train. Carol later tells her cousin of some suspicious behaviour the muffled man exhibited on the train: pouring over maps, avoiding RCMP officers, and pretending to have a broken left arm.

There's little more worth reporting, except to say that The Mystery of the Muffled Man is a novel bereft of mystery. The character who clubs a dog is obviously the villain. Why is he in the northern Ontario mining town? Well, the only thing we know of the area's history is that there had been a bank robbery ten years earlier, and that the money was never found.

By far the most interesting thing about the novel is how little the muffled man figures. Accompanied by friend Dumont LePage, Chris and Carol decide to go ice fishing, get lost in the woods, climb an old fire tower to get their bearings, and discover an abandoned gold mine. After a cave-in separates him from the rest of the group, Chris sees the muffled man digging to retrieve the stolen loot and empties the bullets from his unattended rifle. Chris's father and two RCMP officers show up in the nick of time, resulting in this climactic passage:

"You stay here with the boy," Constable Scott said to Mr Summerville. "We'll deal with him." And, holding their guns at the ready, the two uniformed men moved down the tunnel.Before dismissing The Mystery of the Muffled Man as the weakest novel read this year, it's only fair to acknowledge that it wasn't written with me in mind. The survey that informed the Secret Circle was conducted before I was even born. What's more, I've never so much as considered living in Scarborough.

In five minutes it was over. The muffled man, trapped by the wall of fallen stone, and with an empty gun in his hands, was quickly overpowered.

Trivia: Jack McClelland once encouraged a hard-up Norman Levine to contribute to the series.

Object: A compact hardcover with eight illustrations of varying quality by Joseph Rosenthal. My copy, not nearly so nice as the one pictured above, was purchased three years ago at a London book store. Price: 60¢

Access: WorldCat records a grand total of two Canadian libraries holding the Little, Brown edition. It also lists a 1981 Bantam-Seal paperback, and something titled The Muffled Man (Scarborough: Nelson, 1990).

Interestingly, no copies of the Bantam-Seal and Nelson editions are on offer from online booksellers. The original Little, Brown came and went with a single printing. Though not many copies are listed online, it is cheap. Very Good copies begin at US$8.00. At US$30.10, the most expensive is an inscribed copy offered by an Ontario bookseller.

Remarkably, the novel has been translated into Dutch (Avontuur in een goudmijn) and Swedish (Mysteriet med den maskerade mannen).

Related posts: