Reuben Ship

London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1956

119 pages

Joseph McCarthy was not long for this world when The Investigator was published. Politically and physically, he was all but dead. The American demagogue had been at his most powerful just two years earlier when The Investigator hit Washington. A shell fired from across the northern border, its blast was felt in Congress, the Senate, and was heard, repeatedly, in the Eisenhower White House.

The Investigator began life as a radio play written by Reuben Ship, a Montrealer who'd first achieved acclaim at McGill for his production of Henry IV. He'd gone on to write and produce anti-fascist plays for the YM-YWHA Little Theatre and Montreal's New Theatre Group before chasing opportunity south of the border. This worked for a time. Ship's chief gig was the radio serial The Life Of Riley, but then the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service came calling. Two fellow members of the Radio Writer's Guild suspected Ship of being a Communist. In September 1951, he was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee. He pled the fifth four times, then accused the Committee of jailing people who wanted peace.

In January 1953, Ship was deported. This would've happened months earlier had he not suffering from chronic osteomyelitis. The writer's journey back to Canada began with his removal in handcuffs from a California hospital. He was transported by plane and train to a Michigan prison hospital ward, where he spent the better part of a day. The following evening, Ship was placed in a police wagon, driven across the Ambassador Bridge, and dumped on a Windsor street.

Do not be distracted by the drama leading to The Investigator; the work deserves the greater attention as one of the most impactful lampoons in American history.

Broadcast on CBC Radio on 30 May 1954, it begins with the titular character about to catch a flight. A man named Garson, speaking on behalf of "the Committee," is pushing for the cancellation of a scheduled hearing. The Investigator will have none of it:

"The committee can't stop me. The Party can't stop me. Nothing can't stop me."But then the plane carrying the Investigator explodes in mid-flight. Confused, but angry as always, he is met by Inspector Martin of the Immigration Service:

Martin, a kindly soul, seeks to reassure:

"The fog will lift soon. You won't have any trouble seeing in a moment."

"How did I get here? Where are the other passengers? How many survivors were there?"

"There no survivors, sir."

"You mean I'm the only one?"asked the investigator incredulously.

"There were no survivors."

"What are you talking about?" the Investigator asked angrily. "are you crazy? I'm here... I'm alive aren't I?"

As he awaits the hearing, the Investigator is visited by the Committee: Titus Oates, Tomás de Torquemada, Cotton Mather, and George Jeffreys, 1st Baron Jeffreys, better known as "The Hanging Judge." The four souls assure the newcomer that his application will be accepted, then address the purpose of their visit. They seek to replace the Gatekeeper with the Inquisitor. Says Oates:

"We feel that in you we have a man who can bring to the committee's work the latest inquisitional techniques."

"In our day, it is true, we were without peers, Torquemada explained. "since that time we understand much progress has been made. Compared to you, sir, we are mere novices, and we bow to your superior knowledge and experience."

The Gatekeeper is soon deposed, largely due to the skills of his replacement. Once the Investigator is in charge, he suspends new applications and opens investigations into souls who've been granted permanent entry; the Committee accuses them of "disloyalty, actual or potential."

All are deported, sent from "Up Here" to "Down There."

These deportations and others have unexpected consequences. Down There, Martin Luther and John Stuart Mill are making speeches about the Rights of the Damned, John Milton and Thomas Jefferson are demanding a Congress, and Oliver Cromwell and Tom Paine have organized a Lost Souls Militia.

[T]hat madman, Socrates, keeps asking me if I know what virtue is. Me!" The Voice was full of outrage. "And that lunatic Karl Marx..."

"Which Karl Marx?" the investigator asked hopefully.

"How should I know? There are hundreds of them – all over the place!"

Starring John Draine, James Doohan, and Barry Morse, amongst others, it can be listened to here online thanks to the Internet Archive. A masterpiece, even at the distance of seven decades its impact is immediate and impressive.

And it's surprising how smoothly the script became a book. I delighted in each and every page.

Interestingly, The Investigator has never been published in the United States. It hasn't been published in Canada either, though Ship's script is one of eleven included in All the Bright Company: Radio Drama Produced by Andrew Allan (Kingston & Toronto: Quarry/CBC Enterprises, 1987).

Joseph McCarthy died on 2 May 1957, likely of cirrhosis of the liver. He was 48 years old. Where he is today, Up Here, Down There or nowhere at all is anyone's guess.

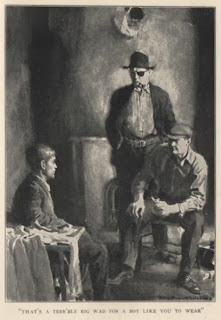

* In the radio play, Canadian rebel William Lyon Mackenzie is one of those whose words are used against him. Neither he nor his writing appears in the book.Access and Object: A compact hardcover in black boards with simple gold type on the spine, the jacket and nine illustrations are by the brilliant Ronald Searle. My copy was once part of the Scarborough Township Public Library's collection.

|

| The Scarborough Township Public Library Bookmobile, c.1956. |

Access: As far as I can tell, the book enjoyed just one printing. Every one of the thirty copies currently listed for sale online is a bargain. At £5.00, a near Fine copy offered by a bookseller in Poole is the least expensive. The most expensive comes from a Bath bookseller who offers a Near Fine edition coupled with a very well preserved copy of the advance proof. Price: £67.00.

It is by far the best buy I've stumbled upon this year.