It's been a disorienting and disruptive year. The home we'd expected to build on the banks of the Rideau became entangled in red tape, an inept survey, and a tardy Official Plan. In our impatience, we left our rental and bought an existing house a ten-minute drive south. We may just stay. If we do, an extension is in order. I'm writing this on a desk at the dead end of a cramped second storey hallway.

All this is shared by way of explanation. I reviewed only twenty books here and in my Canadian Notes & Queries 'Dusty Bookcase' column. Should that number be boosted to twenty-three? Three of the books were reread and reviewed in translated, abridged, and dumbed down editions.

Yes, a strange year... made doubly so by the fact that so very many of the books reviewed are currently available. Selecting the three most deserving of a return to print – an annual tradition – should've been challenging, but was in fact quite easy:

The Arch-Satirist

Frances de Wolfe

Fenwick

Boston: Lothrop, Lee &

Shepard, 1910

This story of a spinster and her young, beautiful, gifted, bohemian, drug-addled half-brother poet is the most intriguing novel read this year. Set in Montreal's Square Mile, is it a roman à clef? I'm of that city, but not that society, so cannot say with any certainty.

M'Lord, I Am Not Guilty

Frances Shelley Wees

New York: Doubleday,

1954

A wealthy young widow moves to a bedroom community hoping to solve the murder of her cheating husband. This is post-war domestic suspense of the highest order. I'd long put off reading M'Lord, I Am Not Guilty because of its title, despite strong reviews from 65 years ago. My mistake.

The Ravine

Kendal Young

[Phyllis Brett Young]

London: W.H. Allen, 1962

The lone thriller by the author of The Torontonians and Psyche, The Ravine disturbed more than any other novel. Two girls are assaulted – one dies – in a mid-sized New England town. Their art teacher, a woman struggling with her younger sister's disappearance, sets out to entrap the monster.

The keen-eyed will have noted that The Ravine does not feature in the stack of books at the top of this post. My copy is currently in Montreal, where it's being used to reset a new edition as the fifteenth Ricochet Book.

Amy Lavender Harris will be writing a foreword. Look for it this coming May.

Of the books reviewed, those in print are:

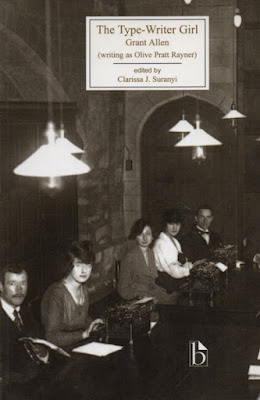

A succès de scandal when first published in 1895, The Woman Who Did is Grant Allen's most famous book. It doesn't rank amongst the best of the fifteen Allen novels I've read to date, but I found it quite moving. Recommended. It's currently available in a Broadview Press edition.

The Black Donnellys is pulpmaster Thomas P. Kelley's most enduring book; as such, it seems the natural place to start. Originally published in 1954 by Harlequin, this semi-fictional true crime title been in and out of print with all sorts of other publishers. The most recent edition, published by Darling Terrace, appeared last year.

Experiment in Springtime (1947) is the first Margaret Millar novel to be considered outside the mystery genre. Still, you'd almost think a body will appear. See if you don't agree. The novel can be found in Dawn of Domestic Suspense, the second volume in Syndicate Books' Collected Millar.

The Listening Walls (1952) ranks amongst the weakest of the Millars I've read to date, which is not to say it isn't recommended. The 1975 bastardization by George McMillin is not. It's the last novel featured in The Master at Her Zenith, the third volume in The Collected Millar.

I read two versions of Margaret Saunders' Beautiful Joe in this year. The first, the "New and Revised Edition," was published during the author's lifetime; the second, Whitman's "Modern Abridged Edition," was not. The original 1894 edition is one of the best selling Canadian novels of all time. One hundred and fifteen year later, it's available in print from Broadview and Formac.

Jimmie Dale, Alias the Gray Seal by American Michael Howard proved a worthy prequel to Frank L. Packard's Gray Seal adventures. Published by the author, it's available through Amazon.

This year, as series editor for Ricochet Books, I was involved in reviving The Damned and the Destroyed, Kenneth Orvis's 1962 novel set in Montreal's illicit drug trade. My efforts in uncovering the author's true identity and history form the introduction.

Praise this year goes to House of Anansi's 'A List' for keeping alive important Canadian books that have escaped Bertelsmann's claws. It is the true inheritor of Malcolm Ross's vision.

And now, as tradition dictates, resolutions for the new year:

- My 2018 resolution to read more books by women has proven a success in that exactly fifty percent of books read and reviewed here and at CNQ were penned by female authors. I resolve to stay the course.

- My 2018 resolution to read more French-language books might seem a failure; the only one discussed here was Le dernier voyage, a translation of Eric Cecil Morris's A Voice is Calling. I don't feel at all bad because I've been reading a good number of French-language texts in researching my next book. Still, I'm hoping to read and review more here in the New Year.

- At the end of last year's survey, I resolved to complete one of the two books I'm currently writing. I did not. For shame! How about 2020?

- Finally, I plan on doing something different with the blog next year by focusing exclusively on authors whose books have never before featured. What? No Grant Allen? No Margaret Millar? No Basil King? As if 2019 wasn't strange enough.

Addendum: As if the year wasn't strange enough, I've come to the conclusion that Arthur Stringer's debut novel, The Silver Poppy, should be one of the three books most deserving a return to print.

But which one should it replace?

Related posts:

The Year's Best Books in Review - A.D. 2017

The Year's Best Books in Review - A.D. 2016

The Year's Best Books in Review - A.D. 2015

The Christmas Offering of Books - 1914 and 2014

A Last Minute Gift Slogan, "Give Books" (2013)

Grumbles About Gumble & Praise for Stark House (2012)

The Highest Compliments of the Season (2011)

A 75-Year-Old Virgin and Others I Acquired (2010)

Books are Best (2009)

The Year's Best Books in Review - A.D. 2016

The Year's Best Books in Review - A.D. 2015

The Christmas Offering of Books - 1914 and 2014

A Last Minute Gift Slogan, "Give Books" (2013)

Grumbles About Gumble & Praise for Stark House (2012)

The Highest Compliments of the Season (2011)

A 75-Year-Old Virgin and Others I Acquired (2010)

Books are Best (2009)

Bach to the Future: A Voice is Calling

Bach to the Future, Part II: Le Dernier Voyage

A Dogs Life and then Some

Bach to the Future, Part II: Le Dernier Voyage

A Dogs Life and then Some

Nature as the Devil's Playground

Getting to Know the Woman Who Did

The True Crime Book That Spawned an Industry

Getting to Know the Woman Who Did

The True Crime Book That Spawned an Industry

Where to Begin with Margaret Millar: A Top Ten

The Return of Jimmie Dale, Alias the Gray Seal

'A Relentless Story of Drug Addiction'

Reviving a Searching Novel about Drug Addiction

The Return of Jimmie Dale, Alias the Gray Seal

'A Relentless Story of Drug Addiction'

Reviving a Searching Novel about Drug Addiction