Keith Edgar

Toronto: National Publishing, 1945

126 pages

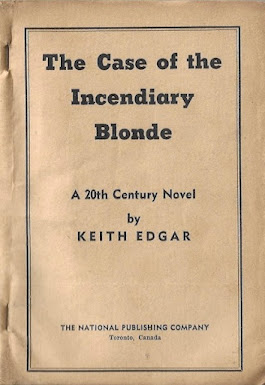

When is a blonde not a blonde? When is a novel not a novel? Is a novel that is not a novel a series of novelettes? These questions weighed as I made my way through Keith Edgar's Incendiary Blonde, sure to be this year's most baffling read. Consider the title page:

'The Case of the Incendiary Blonde' has as its hero, lanky Star-Advertizer photographer George MacGregor. He's first seen leaning against a pillar in Grand Central Station, having fallen asleep whilst waiting to snap Hollywood heartthrob Yvonne La Flame. "We got to get some glammer shots of dis skoit," says a competing shutterbug. "She's got classy gams."

Indeed! Yvonne has legs and she knows how to use them, "perched on a baggage truck to coyly display the 'classy gams.'"

MacGregor wakes up in time to get the pics, but as he makes to return to the Star-Advertizer darkroom he's canoodled and smooched by a "red-haired girl" with "auburn curls." She whisks our hero into a cab, tells him she is a German spy on the run from G-men, and makes him take her to his uptown apartment. Once there, our hero gives her a good sound spanking.

Classic Edgar, it continues apace, adding a Nazi cabbie, an ineffective butler, a sinister trading company, and a Lone Ranger Cap Pistol into the mix. My only complaint is that it's all over too fast. At under seventeen thousand words, 'The Case of the Incendiary Blonde' is not a novel – not even a 20th-century novel. The publisher's note fails to clarify:

MacGregor's adventure is the first and longest of what the cover sells as "STORIES OF MYSTERY & CRIME." Most of the remaining seven are bland retellings of true crime cases.

How bland? Here's a paragraph from 'Murder on the Steamer "Okanagan",' which begins with the 1912 manhunt for Walter Boyd James, a North Dakotan who'd held up a Kelowna general store:

At Penticton, 40 miles away, Provincial Const. Geoffrey H. Aston was stationed. Aston, a soldierly figure who had served in the 17th Lancers and the North West Mounted Police, had received a description of the bandit from Tooth, and immediately acquainted Penticton's Chief of Police, Michael Roche, with details of the Kelowna crime.

'Who Murdered Laura Kruse?' focusses on the still unsolved 1937 killing of a Minneapolis beauty school student. It features this passage:

Witnesses were called to review the case from all angles. They included Claussen, the milkman, Hanson, the motorman, F,W. Perlich, who found the body, M.T. Silvertsen, who found the personal effects, Mrs. Christ Larson [sic], near whose home the murder was believed to have been committed, Mrs. Carl Lind, who saw the flash of light as a car was leaving the alley, Arthur Kruse, brother of the girl, Sheriff Hannes Rykema of Pine County, Irene Chimelski, a friend of Miss Kruse, Ray Harrington, police identification officer, Dr. McCartney, Dr. Seashore, Detective Adam Smith, Arthur Olyson, Walter Hansford, John Anderson, morgue keeper, and Capt. Arnold Neitzel of the 6th precinct police station.Still awake?

When it comes to non-fiction, Edgar isn't much of a storyteller. To his credit, he does stick to facts, and makes only the occasional error. For example, in 'Drink, the Devil, and the Third Degree,' concerning the 1882 murder of Louis Hanier, the victim is a "French wine merchant" when in reality he was a Hell's Kitchen saloonkeeper. The case is broken by Thomas Byrnes, whom Edgar describes, unimaginatively, as "a real-life Sherlock Holmes."

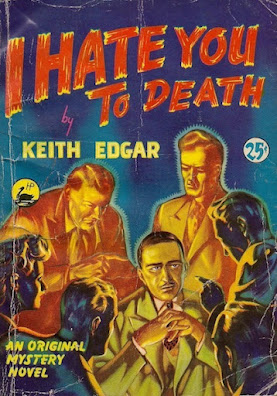

Incendiary Blonde follows I Hate You to Death (1944) and Arctic Rendez-vous (1949) as my third Edgar. Both are quirky, fanciful, strange, perverse, titillating, and never dull.

It's all a damn shame. I was really looking forward to it. The cover art promised the craziest Edgar book yet! The blonde! The devil! The four floating heads! Sadly, none of these feature in the book. I guess I'll never know the significance of the aqua blotch on the lower right-hand corner.

You can't judge a book by its cover, but you sure can sell it. That said, I think Incendiary Redhead is a much more exciting title.

Trivia: Incendiary Blonde was published the same year as a Hollywood film with the same title. It stars Betty Hutton as Texas Guinan, "Queen of the Night Clubs." I'm going to go out on a limb and suggest this is coincidence.

Object and Access: A cheap digest-sized paperback with thin glossy covers, it bears the swan logo of F.E. Howard, the publisher of Edgar's previous books. My copy appears to have been distributed in the U.K. by the now-defunct Rolls House Publishing Company.

Of interest is this notice on the interior cover:

|

| Pages 86 and 87. |

My copy of Incendiary Blonde was purchased earlier this year from a Lincolnshire bookseller. Price: £20.00. The very same bookseller is right now offering another copy, in similar condition to mine, at the very same price!

There is only one other copy listed online. Also in similar condition, it's offered by another UK bookseller at £15.00. Seems a bargain until one reads the shipping cost: C$60.25.

You know which copy to purchase.

Incendiary Blonde can be found at the British Library.