The Ravine

Kendal Young [pseud Phyllis Brett Young]

London: W.H. Allen, 1962

208 pages

Young Barbara Grey "saved for simply ages" to buy a silver bracelet for her mother's birthday. Now that that the day has arrived, she can barely contain her excitement. She manages to make it through her after-school art class, but can't wait for the teacher, Miss Warner, to drive her home. And so, Barbara heads off, cutting through the ravine.

Miss Warner – Christian name: Julie – notes Barbara's absence and ties to be brave. She rounds up her other students, piles them into her station wagon, and drives down into the ravine. It is dark and rainy, mud makes the tires spin, yet Julie Warner presses on, dreading what she might find.

The car hits a particularly bad patch, spins out of control, and shines its headlights on a man resembling the devil standing over what looks to be a vast pool of blood. The figure disappears into the darkness. The pool of blood turns out to be Barbara's red raincoat... which covers her dead body.

Oh, Barbara, why did you go into the ravine? Not six months earlier, Deborah Hurst –

then a student at your very school – was assaulted in the ravine. She hasn't been the same since, and now spends her afternoons waking blank-faced through the streets of your town.

Julie is devastated, of course, but what makes it particularly hard on her is that she has – or had – a little sister who disappeared from the luxurious lobby of the Warner family's Manhattan apartment building. The missing girl was on her way to a violin lesson.

The art teacher comes from a very different place than Barbara and Deborah. Her station wagon replaced a convertible. She works, though she doesn't have to. She has a flat above a drug store, though she can afford better digs. She doesn't have to live here.

But where is here?

Because of title,

The Ravine, and the knowledge that it was written by a Torontonian (whose best-known work is

The Torontonians), I began this novel thinking it was set in Toronto.

It is not.

The Ravine takes place somewhere in New England. The setting is referred to as a "town," though it appears to be a much larger municipality. There are two daily newspapers, a "foreign" quarter, and downtown streets that are unfamiliar to the art teacher. And yet, the community is so small that everyone knows everyone else; Julie, being relatively new, is the exception.

She's brought into contact with several people as a result of poor Barbara's murder. There's Dr Greg Markham, who treated Deborah Hurst, and has been following her movements ever since. Tom Denning is a newspaper editor, whose chief concern is circulation. Captain Velyan, head of the police, is doing his best to deal with crimes of a sort that just don't happen in a town like this.

Of these three men, Greg is the most important. Struck by Julie's testimony at the coroner's inquiry into Barbara's death, he trails her to a filthy café in which she has taken refuge from reporters. He asks her to dinner that evening. By the end of the date, during which they share one brief kiss, they've become an item.

Julie runs around behind her new boyfriend's back in enlisting Denning and Velyan to entrap the devilish man. Meanwhile, Greg puts together a plan of his own, which he keeps from Julie. Neither action bodes well for a long-term relationship.

The educated, lithe, artsy, blonde, daughter of wealth, Julie is a type; she's as familiar as Dunning, the alcoholic newspaperman, and Velyan, the out-of-his-depths police captain. Dedicated doctor Greg is also a type, though I'd argue that his day has passed. From their very first meeting he looks to exert control over Julie's life:

"Your trouble is that you think too much about other people, Julie. You need someone who will put you first. Do I do that with your permission, or without it?"

The afternoon newspaper is anxiously awaited, a hospital switchboard operator causes concern, meals are taken in drug stores, and cigarettes are offered all around. This is a novel of another time, and nowhere is is more evident in its depiction of the ravine itself.

At midnight on that Thursday night, the ravine was as dark and silent as the valley of death itself. Its thick, black canopy of branches was as motionless as the windless darkness, as secretive as the deep earth trough it shielded.

Unseen, soundless, the sullen pools in the depths of the ravine swelled and spread, bloated by rivulets of rain-water which slithered inexorably down its steep sides: which crept around the holes of the trees; which filtered noiselessly through the lesser resistance of undergrowth obscene with funguses which had ever seen the light of day.

Shunned even by the owls, it knew no movement other than this dreary invasion of last minute streams which it would eventually absorb with slow reluctance. A reluctance not duplicated by the morbid eagerness with which it took the night into itself and became one with it.

Severed, as if by a will of its own, from all but the powers of darkness, it seemed to brood with deliberate malice upon the evil secrets it guarded: seemed to reveal in a black, inanimate triumph belonging only to itself.

Brooding over a dark past, savouring the taste and smell of recent death, the trees and bushes which were its real substance became linked one to another in a tangled threat as ugly as it was positive.

More fully realized than the encircling town, the ravine is seen by a great many in the community as "a tangled, cancerous growth." It is an evil place. The reader is told there are those who want it left alone, but none of them feature as characters.

After Deborah's assault, Denning's paper launched its "Abolish the Ravine" campaign, painting a picture of a changed landscape with roads, scattered shade trees, and "artificial drainage." It calls for light standards "as unobstructed as the moon and stars above." The campaign was a success in that circulation increased. Barbara's murder provided a second boost.

The novel's brief denouement, which takes place the month after Barbara's murder, features a passage in which the first snows begin to fall, "clean, white, and beneficent, gently covering the acres of raw stumps which are all that remained of the ravine."

For this reader, it was an unhappy ending.

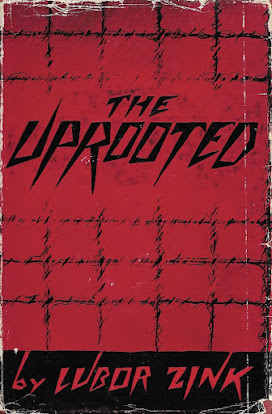

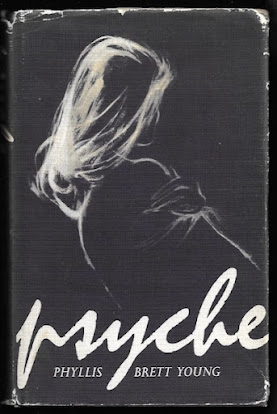

Trivia: The dust jacket features an advert for other W.H. Allen titles, including

Psyche, Phyllis Brett Young's first novel:

Kendal Young is the pseudonym of Phyllis Brett Young whose latest novel will be one of 1962's major films. It is the fascinating story of what happens to a young girl after she has been kidnapped.

I'm sorry, which novel will be one of 1962's major films?

The reference is to

The Ravine;

Psyche is the story of the kidnapped girl*

The Ravine was not a major film of 1962 or any other year, though an adaptation was shot and released nine years later under the title

Assault. It is not to be confused with

the 1971 gay porn film of the same title.

Must say, of the six novels W.H. Allen advertised on the dust jacket, the one that most intrigues is

Touch a French Pom-Pom, with its promised probing of "the curious situation of four people with the same peculiar desire."

*Addendum: Phyllis Brett Young scholar Monika Bartyzel informs that the “major film” reference was indeed to

Psyche: "Victor Saville had the movie rights, and cast Susannah York to play the dual roles of Psyche and her mother. It was announced far and wide, but then he retired from filmmaking in ill health (his last credits are from 1962) and the project floundered." She adds that “'Latest novel' is definitely a poor choice of words, especially since

The Torontonians came out in 1960, the year after

Psyche."

Thank you, Monika!

Object: A compact hardcover made of red boards. My copy was purchased for five American dollars (with a further twenty for shipping) from a dishonest New Zealand bookseller. Described as "Ex library used copy with wear and tear but overall clean square copy," the thing came apart in my hands.

Access: As far as I can tell, the W.H. Allen edition enjoyed just one printing. Pan published the first paperback edition in 1964, followed by a 1971 movie tie-in as

Assault.

A German translation,

Mein Mörder kommt um 8, was published in 1966.

The Ravine is held by Library and Archives Canada and McMaster University.

That's it!

Copies of the

The Ravine is surprisingly uncommon.

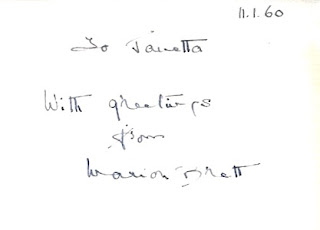

The Ravine was published in Canada by Longmans, yet there is no evidence of its existence online. I know of it thanks to Amy Lavender Harris, who owns a

signed copy. As of this writing, there are no copies of the Allen and Pan editions listed for anywhere. Two copies of

Assault are currently listed for sale online at £2.50 and £3.50. Get 'em before their gone. Like the Longmans, this edition isn't recognized by WorldCat.