The Gorilla's Daughter

Thomas P. Kelley

Toronto: News Stand Library, 1950

Note: The Gorilla's Daughter is the most sought-after Canadian paperback. It is also the most notorious, though I would argue this has everything to do with the cover. Because copies are so scarce, and access so limited, I'll be relaying the story of the gorilla's daughter from beginning to end. There will be spoilers. Criticism will be kept to a minimum.Blonde and beautiful Diana Lynn, nineteen-year-old daughter of archeologist and big game hunter Professor Theodore Lynn, is abducted by Bontu, a five-hundred-pound male gorilla, whist on safari in Equatorial Africa. She'd heard stories of native women who had been carried off by "the hairy men of the trees," but had dismissed them as products of "the wild imagination of the village natives, the witch doctors and the porters." Now, she knew different. Or was she having a nightmare?

But, no, it isn't a bad dream; rather a living nightmare.

Do you think this impossible? I did, but was soon set straight:

"Oh, you fool. You blind fool. Do you not know history as you should? Can't you realize that the ancient Druids of England mated humans with animals? Don't you realize that the ancient Roman Emperor Caligula, chose a beautiful and snow-white mare for his mistress?"Blade Runner being my favourite film, and Taffy's Snake Pit Bar being a favourite hangout, this particular example stood out:

"If you know anything about Egyptian history, you will realize that the great Queen Hetshepsut, always employed an asp – yes, a slimy reptile, a snake – for her moments of love. History can't deny that."Can't it? In my defence, I minored in Canadian history. For what its worth, I have read Marian Engel's Bear, and do not recall a pregnancy.

|

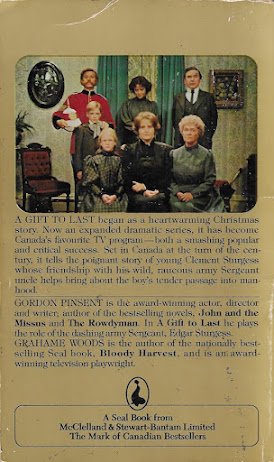

| Bear Marian Engel Toronto: Seal, 1977 |

Fourteen years pass, during which mother and daughter cement the closest of bonds. Though Tara is unable to communicate verbally, except in the language of the gorillas, she is taught to write and proves herself every bit as intelligent as her English educated mother. Tara grows strong while her mother grows weak. No longer blonde or beautiful, Bontu's abuse has taken a great toll and her body is giving out.

Escape attempts are long in the past; Bontu was always quick to recapture and punish her. Diana will come to accept that she can never return to London society:

The only positive thing Diana takes away from the meeting is a rifle, which she then uses to kill Bontu.

Ill health claims her shortly thereafter.

Here the narrative shifts abruptly to focus on handsome Bob Wickson. The son of American steel baron Andrew J. Wickson, he's "one of those fortunate young men who has too much money" and not much to do. Looking for adventure, he heads for Cape Town where he encounters an old drunk who tells him a story of Atlantis which has the survivors of that mythological sunken continent settling in the heart of Africa where they built a city of untold wealth encircled by "The Forbidden Mountains."

He has a map to sell.

Bob buys it for £2500 – roughly £138,000 today – telling himself that there's one chance in a hundred that the drunk is telling the truth.

The gamble pays off quickly and the Forbidden Mountains are found in the very next paragraph. As they approach, there is unrest amongst Bob's native guides and porters. It's left to his chief gun-bearer to enlighten:

"The men are afraid, they do not want to go any further. We are approaching the land of the evil spirits, Bwana. Our ancestors have told it is a terrible place of death and destruction, where huge beasts ten times larger than the biggest elephant, fly through the air and devour everything they see!"

To say that young Bob Wickson was annoyed, would be putting it mildly.

Tara shoots the panther, saving Bob's life, and jumps to the ground.

Hey, she has a nice personality.

The tribe of Tara made no discrimination as to sex – wives meeting the same fate as their husbands – while infants and children were raised upwards by shaggy paws which dashed their heads against the massive and towering pillars. Screams and shrieks arose, then frantic cries for mercy. But the beasts of Tara could not understand the words, and mercy was a thing unknown to them.

"Well, Tara, the truth is that you are not a human. To be sure, you have the most glorious human body that ever trod the earth. But – but your face is that of a beast. Oh, don't you see – you're a freak, a grotesque freak – part human, part beast. If we were ever to go to my country, people would shudder at the sight of you!"

She says nothing more, rather collapses on the alter upon which Bob was to have been sacrificed.

Eight days later, Bob's ankle has all but healed. He manages to climb the range and return to his camp, only to find that his guides and porters are gone. The fortunate young man with too much money has two hundred miles to traverse without arms, support or supplies. As the terrible truth sets in, Tara reappears to guides and protect him on a trek that would otherwise result in certain death.

Half-beast or not, he realized that in this strange creature he has found nothing but goodness – loyalty, unselfishness and honesty. Yes, perhaps she was some queer quirk of nature, but there was something in her that was fine, FINE!He encircles Tara in his arms and holds her body to his, a motion that in her tribe signifies acceptance of a mate. Their embrace is broken by a charging lion. Tara whips out her knife and is killed saving her mate.

This is not their story, it is the story of Tara, the gorilla's daughter.

Bonus: The Gorilla's Daughter ends on page 127, falling far short of the standard News Stand Library title. Padding is provided by a thirty-page science fiction story titled 'Awaken the Dead!' by Halls Wells.

Set in 1947, it concerns a wealthy Wall Street investor who, at age ninety-two, is doing his darnest to stave off death. To this end, he has himself refrigerated so that he might be thawed out when there are cures for his ailments.

About the cover: Is the woman meant to be Diana or Tara? Either way, the illustrator errs in that both are blonde. In fact, Tara is described as having platinum blonde hair.

Object and Access: A typical NSL mass market paperback. The rear cover copy does indeed consist of excerpts, the lone difference being "blonde." Kelley uses "blond" throughout the novel. I prefer the former.

Library and Archives Canada, McMaster University, and the University of Calgary have copies, but that's it.

As of this writing, no copies are listed for sale online.

.jpg)