Still more than two weeks left in the year, but not too early for this list. Given my schedule these days, I know the book I'm reading right now will be the last finished before the ball drops in Times Square. I also know that it won't make the grade.

What's the book? I'll let that remain a mystery, though the sharp-eyed will spot it amongst other 2016 reads pictured above.

This year, I reviewed twenty-seven books – here and in the pages of Canadian Notes & Queries. That's just three more than in 2015, and yet I had a much harder time deciding on the three most deserving of a return to print. These are they:

The Midnight Queen

May Agnes Fleming

Who'd have thought this 19th-century novel of the Plague Year, would be such good fun. It's a fast-paced, crazy ride featuring a masked medium, a killer dwarf, long-lost siblings, and highwaymen and whores playing at being aristocrats. It's also quite well written.

There Are Victories

Charles Yale Harrison

An ambitious, daring novel by the man who gave us Generals Die in Bed. Set in Montreal and New York, this isn't a war novel, though it does deal with its devastating effects. Flawed, but brilliant, the novel's scarcity adds to the need for reissue.

For My Country [Pour la patrie: roman du XXe siecle]

Jules-Paul Tardivel

In this 1895 novel, Satan looks to secure his hold on the Dominion of Canada, only to be thwarted by divine intervention and something resembling a fax machine. The original French remains in print, but not this 1975 translation by Sheila Fischman.

Regular readers know that nearly every Margaret Millar I read is recommended for republication. This year, I read only one of the Grand Master's novels: Do Evil in Return. It would've made the list had it not been announced for republication as part of Syndicate Books' Complete Margaret Millar. Look for it in March.

Three books reviewed here this year are currently in print:

|

| The Man from Glengarry Ralph Connor [pseud. Charles W. Gordon] Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2009 |

|

|

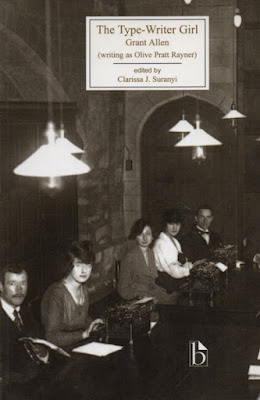

Olive Pratt Raynor [pseud. Grant Allen]

Peterborough, ON: Broadview, 2003

|

|

The Cashier [Alexandre Chenevert]

Gabrielle Roy [trans. Harry Binsse]

Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2010

|

Gambling With Fire

David Montrose

[Charles Ross Graham]

The fourth and final David Montrose novel. Here private investigator Russell Teed, hero of the first three, is replaced by the displaced Franz Loebek, a once wealthy Austrian aristocrat caught up in Montreal's illegal gambling racket.

The Keys of My Prison

Frances Shelley Wees

In the 2015 edition of the Year's Best Books in Review I made reference to a book I was hoping to revive. "If successful, it'll be back in print by this time next year," I wrote. The Keys of My Prison is that book. A novel of domestic suspense set in Toronto, it should appeal to fans of Margaret Millar...

And on that note, as might be expected, praise this year goes to New York's Syndicate Books for The Complete Margaret Millar. The Master at Her Zenith and Legendary Novels of Suspense, the first two volumes in the seven-volume set are now housed in the bookcase. The next, The Tom Aragon Novels, is scheduled for release on the tenth of January.

Great way to start the new year.

Related posts: