The Cannibal Heart

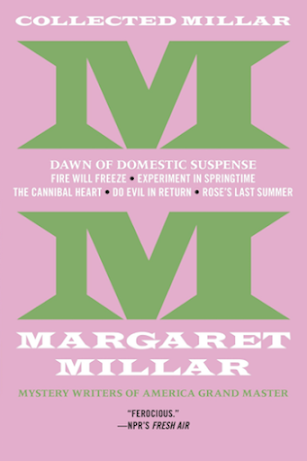

Collected Millar: Dawn of Domestic Suspense

Margaret Millar

New York: Syndicate, 2017

In Margaret Millar's bibliography,

The Cannibal Heart falls between

It's All in the Family and

Do Evil in Return. As a light and lively novel for children, the former is her most unusual; the latter, which deals with the tragic consequences of a refused abortion, is both her most controversial and most timely.

The Cannibal Heart isn't so noteworthy. Of the fourteen Millars I've read to date, it ranks below the average, which is to say that it is merely very, very good.

The novel takes place almost entirely on the grounds of a large California oceanfront estate rented by the Banners: Richard, Evelyn, and their active eight-year-old daughter Jessie. The property belongs to a Mrs Wakefield, whose efforts to sell have been thwarted by a draught. Her employees, cook Carmelita and caretaker husband Carl, live with their adolescent daughter Luisa in a three-room apartment above the garage.

Someone spoken of, but not seen, Mrs Wakefield grows as a figure of mystery in the initial chapters. She at last appears as an attractive thirty-something widow worthy of sympathy. In the space of the previous two years, Mrs Wakefield has lost her husband John, as well as Billy, their only child. John was a naval engineer, a wealthy man whom Mrs Wakefield met as a schoolteacher from a small Nebraska town. Their child, Billy, was... well, let's say Billy is revealed gradually.

But then things in Millar novels are always revealed gradually.

It's suggested that the Banners have come from the East Coast to recover from some sort of domestic disturbance. Might Evelyn's issues with jealousy be related? Even when alone, Evelyn and Richard maintain the pretence that the move has to do with expanding Jessie's horizons.

We come to know Mrs Wakefield intimately. The life she shared with her husband is something of a blur, but her experience giving birth to Billy and the days that followed are too clear for comfortable reading.

As always, Millar delves deeply into the inner lives of its characters, children included. Fifteen-year-old Luisa, a minor character (no pun intended), is a good example. Like most teenagers, she dreams of life far from her parents. In her fantasies, she's a singer with beautiful blonde hair, fawned over by handsome men with lots of money. But this can never happen in the way she imagines. Reality intrudes, reflected in the words of her father, who recognizes that she has been born "half-mulatto, half Mexican."

Syndicate Books, Millar's current publisher, lists

The Cannibal Heart as a novel of suspense. It isn't.

The Cannibal Heart belongs with

Experiment in Springtime and

Wives and Lovers, the two (and only two) novels the publisher categorizes as "OTHER NOVELS." As I wrote in a previous review, in these people do bad things; as do we all. While the reader might anticipate murder – after all, Millar was a mystery writer – nothing of the kind occurs. No character commits a criminal act, though one comes close. That that same character is the most sympathetic, most wronged, and most cheated, leads me to wonder whether I'm not right to thinking

The Cannibal Heart below average Millar.

Dedication:

"For an old friend, a fine critic, and an ever-imaginative angler, Harry E. Maule."

An editor at Random House, Harry Edward Maule (1886-1971) accepted Millar's 1956 Edgar Allan Poe Award for

Beast in View.

Object and Access: A bulky trade-size paperback, Dawn of Domestic Suspense is the second in the attractive (if cramped) seven-volume Collected Millar. The Cannibal Heart was the last to be read; the others have been reviewed in previous blog posts:

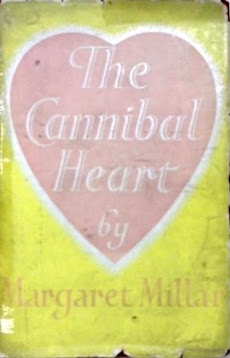

The Cannibal Heart is the ninth of Margaret Millar's twenty-six novels. It was first published in 1949 by Random House; Hamish Hamilton issued a British edition the following year. The Random House jacket (above right) better reflects the novel.

The Cannibal Heart was not a commercial success. It had spent over three decades out-of-print when, in 1985, International Polygonics issued the first paperback edition. A Thorndike large print edition followed fifteen years later.

As might be expected, The Cannibal Heart is uncommon in our public libraries. That serving Kitchener, the city in which Margaret Millar was born, the city in which she was raised, the city in which her father served as mayor, does not have a copy.

The Collected Millar remains in print. Used copies of The Cannibal Heart listed online begin at €6 (a first edition lacking jacket). At US$225, the most expensive is the same edition in "fine, bright dust jacket." Do not read the bookseller's description as there is a spoiler.

The Cannibal Heart has enjoyed two translations: French (Le coeur cannibale) and German (Kannibalen-Herz).