Repent at Leisure

Joan Walker

Toronto: Ryerson, 1957

284 pages

Thus grief still treads upon the heels of pleasure:Married in haste, we may repent at leisure.

— William Congreve, The Old Batchelour (1693)

The title is a spoiler.

Repent at Leisure tells the story of young war bride Veronica Latour, sole child of London physician Charles Phelps and wife Amanda. It begins at Heathrow, where Veronica is about to board a repurposed Liberator for a flight to the New World:

She wore a wheat-coloured Irish linen suit, with an ascot of tan silk stabbed by a delicate diamond brooch. A very new, rather small mink cape was slung over her arm. Beside her brown crocodile pumps there was matched rawhide luggage tagged with BOAC labels, "Montreal".

Whether handsome husband Louis Latour is aware of his bride's imminent arrival is unknown. Veronica's departure is unexpected. Doctor Phelps chanced to get his daughter a seat through one of his patients, an executive at BOAC. Veronica sent Louis a telegram, but has received no response. Not that that means anything; it's not been forty-eight hours and this is 1946.

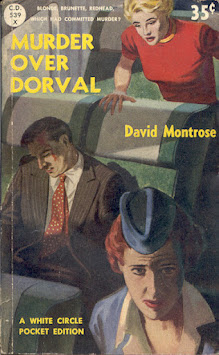

As with

David Montrose's Murder Over Dorval, I was fascinated by the author's descriptions of post-war air travel. During one leg of the flight, an "unembarrassed steward" directs Veronica to the toilet facilities. She pulls aside curtains and finds herself almost entirely surrounded by glass. Where once been a tail-gunners perch now sits a chemical toilet. The most magnificent view of the Atlantic Ocean by moonlight is afforded those in need of relief.

After stops to refuel in Shannon (at which passengers depart the plane for dinner at the airport hotel) and Gander (breakfast), the pretty young newlywed's plane lands at Dorval.

But where is her groom?

What do we know about Louis Latour, anyway?

On the evening they met, Veronica had plans for a library book and small box of rationed chocolates, but these were dashed by her best friend. "Sarah had nagged and nagged, and reluctantly she had changed into a blue and white silk print with red velvet cummerbund and red high-heeled red sandals, and met Sarah and John at Grosvenor House."

|

| Grosvenor House, c. 1940 |

It was in the hotel ballroom that Veronica met Lieutenant Louis Latour, a "devastatingly handsome young man with very black hair and vividly blue eyes and a small curved flash on the shoulders of his service khaki which said, in red letters, CANADA."

Who could resist?

Veronica's parents never much cared for Louis. There was no real reason for this, rather a feeling. The worst Dr Phelps could say of the young French Canadian was that he "murdered the King's English," all the while allowing that Louis did so in an "attractively continental way." A discrete enquiry to lieutenant's commanding officer revealed an exemplary military record.

Veronica and Louis married within weeks of meeting. The couple were together a few weeks more in the Phelps' large London home before Louis was shipped back to Canada.

And now, Veronica was joining him.

At Dorval, Veronica finds herself stranded with monogrammed luggage, hat box, and Elizabeth Arden make-up case next to her brown crocodile pumps. She's rescued by friendly fellow traveller Alan Nash, who offers her a lift to town. Any hesitation Veronica might feel in accepting the offer from a man is settled by the sight of Alan's sister:

Jane Nash was quite lovely. Brown shining hair and laughing hazel eyes like her brother's, only his weren't laughing now but strangely thoughtful. She like the way Jane looked as crisp as a lettuce in a green and white print with china bracelets heavy on one wrist and tricky white suède sandals strapped over incredibly fine nylons.

Joan Walker once worked as a fashion illustrator in London, and it shows. The Liberator flies through dark clouds "like scarves of black chiffon" while Veronica, with "hair back like satin from her temples," gazes out at a Milky Way "stretched like a bride's veil across the sky."

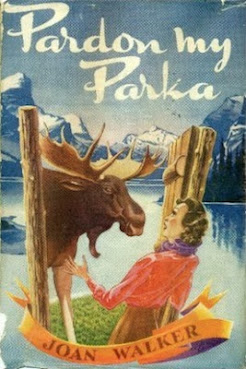

Walker was also a war bride. Her first Canadian book,

Pardon My Parka (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1954), provides one account of her early married life in Val d'Or, Quebec. She appears to have a better time of it than Veronica Latour;

Pardon My Parka won the 1954 Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal for Humour.

Louis has created a fiction. When war was declared, he'd enlisted in order to escape a large, unloving, incompatible, impoverished family. During his six years overseas, Louis worked at improving his English, his table manners, and had fabricated a backstory which had him as an orphan raised by a kindly maiden aunt (recently deceased). After the war, after marriage to Veronica, he'd returned to Montreal a different man. Louis bought tasteful suits, fresh shirts, and applied for positions for which he was wholly unqualified.

As I myself have learned, good looks and exemplary table manners only get you so far.

Louis didn't meet Veronica's plane because he was didn't know what to do. He worked that day stocking shelves at a grocery store (his detested brother-in-law, the manager, gave him the job), and then got drunk. It isn't until the wee hours that he goes to see his wife, pounding on her hotel room door. Ridicule, vomit, and violence follow:

He swayed to where Veronica was sitting on on the edge of the bed, her eyes bright with tears of helpless laughter, He slapped her face. He said something in French which was neither civilised nor cultured.

Veronica's face went very white, except for the red marks of his hand. She stared at him silently, incredulously.

As a surgeon's daughter she knew had been on the verge of hysteria [sic]. She knew, too, that Louis had done the best thing possible by slapping her. But she also knew, with a cold certainty, that the reason for his blow had other causes and that he had no idea whatsoever of its therapeutic worth.

It was like waking up and seeing a stranger. She had loved Louis deeply in England, but now he was unknown. An interloper in a loud, impossible blue suit, a belligerent, drunken, unattractive creature. She didn't love him at all.

No other scene is nearly so dark as this; in fact, the better part of the novel is bright and "gay" (a word as ubiquitous as "cigarette"), as reflected in the chosen decor of the couple's first Montreal apartment. Veronica displays great interest in her adopted country, navigating with good cheer, though she does have a tendency to look down her nose. Today's reader will find these depictions of the past fascinating, and may share in her snobbery.

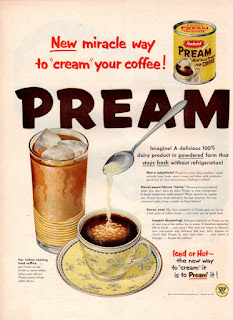

Was there really a time when the most sophisticated Montrealers drank "Instant Coffee" with Pream?

What is Pream, anyway?

Veronica's love for Louis never returns, but she's happy; he really knows how to please her in bed. The young English expat sets out to mould her husband into her ideal, and it is to her credit that she succeeds.

But is that enough to save her marriage?

Cosgrove might have anticipated the ending.

Object: A compact hardcover, there's something of the British in its dimensions and design. Sure enough, closer inspection reveals that it was printed by Merritt and Hatcher Ltd, London and High Wycombe. I'm assuming the printing was a spit-run with Redman, which in 1957 issued the novel in the UK.

The dust jacket illustration is unusual for Ryerson in that it features the artist's signature. My thanks to Jesse Marinoff Reyes, who identified it as the work of British artist Henry Fox. I expect I'm not alone in seeing something of a 'fifties Harlequins in the illustration and design. In fact, there was a Harlequin edition, but with a very different illustration:

The Ryerson is all wrong in that Veronica wears a wheat-coloured suit, and not cerise. The Harlequin is wrong in that it features an impossible view (though Veronica does own a green corduroy dress).

Access: First published (abridged) on 7 October 1957 in the

Star Weekly with an illustration by Vibeke Mencke. Despite winning the

All-Canada Fiction Award,

Repent at Leisure enjoyed one lone printing. This should come as no surprise to anyone familiar with the prize. The used copies listed for sale online aren't plentiful, but they are cheap. As of this writing, there are four Ryersons, ranging in price from $11.18 to $17.25. Curiously, those with dust jackets are the cheapest.

The Redman is nowhere in sight.

Related posts: