In Passion's Fiery Pit

Joy Brown

Toronto: News Stand Library, 1950

In Passion's Fiery Pit features a misprint unlike any other I've seen:

Not Joy Brown's fault, of course, but it does say something about her publisher. News Stand Library didn't much care what it published or who it published. In its stable, Joy Brown stands as lone mare alongside Hugh Garner, Ted Allan, Al Palmer, Raymond Souster and H. Gordon Green in having had something of a writing career. Given her early struggles with punctuation, this is truly remarkable.

In Passion's Fiery Pit was Brown's second novel. The first, Murdered Mistress, had been published by News Stand Library a few months earlier. Night of Terror, her third, was a pre-romance Harlequin. It hit the stands about eight weeks later.

Three novels in one year. Do not be impressed.

This one begins with a bit of a cheat. What's depicted as murder will later be revealed as assault. The victim, Alicia Wallace, turns up dead on the very next page just the same. Her body is discovered amongst the exotic plants in the conservatory of wealthy bachelor Robert Roget.

Yes, a conservatory. Roget builds upon the cliché, sniffing: "It's damned embarrassing… I mean with a houseful of guests."

Houseful? Well, there's Paul Stewart, wife Gwyneth and brother Bridge. The Greys – Tim and Trixie – are also there. That's five, right? Not really a houseful, not for a mansion, though things get a touch more crowded when the police show up. Detective Dan Weaver leads the investigation.

Dan's an interesting fellow. The novel's hero, when first seen he's drinking in the beauty of Alicia's cooling corpse… the curve of her cheek, her full lips and her shapely calves. "She was the kind of girl Dan Weaver had been wanting to meet for a long time. Unfortunately, she was dead."

The trail leads straight to the Three Bells nightclub:

Dan Weaver did a double take. The somebody sitting on the piano should have been lying in a steaming conservatory with her skull crushed. But here she was singing in a hushed, tuneless voice. Nobody seemed to care what sort of a singer she'd make.Here the author dodges cliché by making Alicia's doppelgänger, torch singer Phyllis, a younger sister. Alicia may have been as bad, but she was no evil twin.

Because Dan clearly has a type, he falls for Phyllis, and redoubles his efforts to solve the murder. He's not afraid to cut a corner in getting at the truth. This Canadian is fully prepared to walk into a room without knocking first.

Sergeant Cummings, Dan's superior, is infuriated by this maverick behaviour:

"I've mentioned that to you before. You're still on the force, you know, even if you're not in uniform, and the rules are that..."The two boudoir scenes aren't all that much – a fully clothed woman walks out of a bedroom, a man comforts a grieving widow – and neither is pertinent to the case. Dan is overselling things. He really has no idea what he's doing. I'm not sure Brown did, either. In the course of his investigation, Dan settles on Alicia's former husband Jeff Wallace as the murderer, for no other reason than they divorced. You know, acrimony and all that. Blackmail, too, though this makes no sense.

"But you find out more this way. I make a few exceptions to a few rules. I like a variation of a theme. And see what happens? I find two boudoir scenes in one afternoon." Dan waved his hand, "What is this thing called procedure."

Cummings frowned. He had mentioned things like this to Weaver before, but the younger man paid no attention.

As Alicia's ex doesn't seem to be around, Dan becomes convinced that one of the men present on the night of the murder is in actuality Wallace. He's proven wrong in a most public way by Phyllis, but feels no embarrassment. Dan's big break comes at the end of the novel when the murderer drinks too much and spills the beans. Sergeant Cummings is impressed.

In truth, Dan isn't much of a detective, and In Passion's Fiery Pit isn't much of a mystery. It's no wonder that News Stand Library tried to sell the thing as something spicy: "GREEN EYES - RED HAIR - and FLAMING LIPS", but no mention of murder. Sadly, the hottest action involves women primping before mirrors and crossing rooms in varying states of undress. There's lots of lingerie, though much of it is superfluous:

She scampered ahead of him into the bedroom, and then proceeded to dress before his interested eyes in such a flurry of panties, garter belts, bras and stockings that she was fully clothed in a brief moment.Brief moment.

No pun intended.

To my great surprise, the word "diaphanous" doesn't feature.

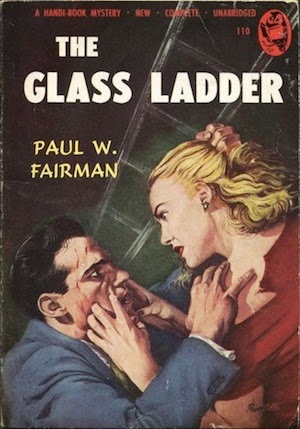

Object and Access: A typical News Stand Library production with requisite 160 pages. The cover is by Syd Dyke.

My copy was purchased in June from a New York bookseller. Price: US$4.00. I was lucky. Just four copies are listed for sale online, the cheapest of which goes for C$20.00. At C$140.00, the one you want to buy is graced with another of those odd and uncommon NSL dust jackets.

Not listed on Amicus or WorldCat.

My thanks to Bowdler at Canadian Fly-By-Night for the image of Murdered Mistress.

Related post: