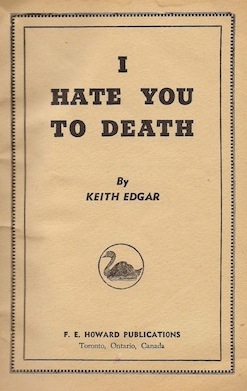

I Hate You to Death

Keith Edgar

Toronto: F.E. Howard, 1944

Seven writers lure hated publisher Basil Hayden to a private dining room on the fourteenth storey of a swanky New York hotel. The plan is to hold him captive and read aloud their rejected works until he pays up. In the darkened room, under hooded reading light, mystery writer Mortimer Tombs (né Smith), is first in line. Before beginning, he advises:

"Remember, Mister Basil Hayden, that while I am reading this you will be feeling the concentrated HATE of seven people. Seven people in this room are hating you. Feel their hate!"

Our narrator, Mort is fifteen or so minutes into his "thrilling mystery"

Blood on the Ceiling when it is discovered that Hayden is dead. "Heart attack," pronounces one of Mort's fellow frustrated writers. The group of seven are about to call for the hotel doctor when one of their number, humorist Isaac Grimm, suggests the police. And so, a new plan is born in which the frustrated writers will cry "Murder!" – then mine the scandal.

Grimm's gamble works. Headlines like the one borrowed for the title of this post pepper newspapers, Hollywood comes calling and the agents move in.

Blood on the Ceiling is sold to a publisher sight unseen, while others try to sign up the mystery writer for further work.

Then comes the news that Hayden really was murdered. Brian Haggerty, the detective assigned to the case, fingers Mort as prime suspect, and we're off... rather, they're off. For no other reason than he is a mystery writer, Haggerty has Mort tag along as he visits and revisits the six other writers.Though nothing furthers the plot, the reader is treated to several encounters with the blonde, the beautiful Audrey Allen, a contributor to the dead publisher's

Passionate Love monthly. It's in the first of these that we're afforded the opportunity to rethink narrator Mort's status as hero of

I Hate You to Death. Consider, if you will, the man's reaction when Audrey suggests that he wants to marry her for her money:

I jumped to my feet, spilling chicken sandwiches on the floor and breaking the plate. I grabbed her by the shoulders and shook her until her lovely teeth rattled.

You – know – damn – well," I panted, "that – I – make – a – damn sight – more money – than you!"

I shoved her back in the chair and snarled, "One of these days I'm going to beat the living bejesus out of you and knock some sense into your head!" I returned to my chair and sat down again.

Haggerty hadn't moved.

Haggerty doesn't move much in this novel, though he is as a man adrift. A mystery himself, the detective's speech alternates between hayseed and a metropolitan sophisticate. Haggerty's ineffective interrogations invariably include a feeble request for the murderer's name. "If only I could pin down the underlying motive", he whines to Mort, before making a bold pronouncement:

"Why was Basil Hayden killed? When I know that I'll know he murder. I must have the answer here somewhere, and damn me if I don't get it tonight."

"I hope you do," I answered him. "I'm fed up with the whole thing."

I concur.

The exchange between Haggerty and Mort takes place on 114 of the novel's 127 pages. The detective does indeed "get it" that night... but not through his own work. Ultimately, the murderer reveals himself through a suicide note – printed in full on pages 124 and 125 – in which he hints at his motivation. Author Keith Edgar cheats here, by sliding all sorts of new stuff under a slowly closing door, and by having Haggerty quickly announce, "The case is closed."

The last words are left to Audrey and Mort::

"Murders are fun," mused Audrey, "if you don't happen to be a friend of the murderer."

I guess that summed up the situation neatly.

I do not concur.

Object: A digest-size paperback numbering 127 pages in length, the cheap paper and flimsy wraps have held up well these past sixty-eight years. The keen-eyed will have noticed that only six of the seven hate-filled writers are depicted on the cover – one of the two women is missing. I'll add that not one of the five men depicted fits the description of "stout and baldish" Gus Hamilton, writer of "pseudo-scientific thrillers".

Access: A rare book, of all our libraries only those of the City of Toronto and the University of Toronto have it in their holdings. Four copies are listed for sale online – all from American booksellers, they range in price from US$22 to US$54.

Cheap, I'd say.

Related post: