|

| Pussy Black-Face Marshall Saunders Boston: Page, 1913 |

Related posts:

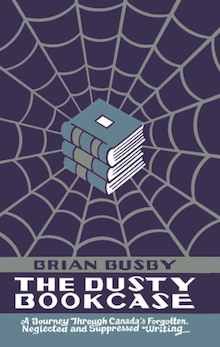

A JOURNEY THROUGH CANADA'S FORGOTTEN, NEGLECTED AND SUPPRESSED WRITING

They sidle up to me with a conspiratorial air and murmur into my ear the name of some author or book, all this in the same tone of someone asking for a condom or a suppository in a drug store. Others are more evasive still; they shower me with meaningful glances and ask me to recommend "something a little out of the ordinary" or "something with a kick to it."Jodoin quickly comes to resent the extra work involved in retrieving volumes from the sanctum sanctorum, recognizing most aren't at all interested in liberty and freedom of thought: "If these jokers are looking for an aphrodisiac, they can find more effective ones."

* Researching this piece, I was amused to discover that Georges Sagehomme's Répertoire alphabétique de plus de 7000 auteurs avec leurs ouvrages au nombre de 32000 (romans et pièces de théâtre) qualifiés quant à leur valeur morale (1931), was revised nine times; the last – published twenty-nine years after his death – is Répertoire alphabétique de 16700 auteurs 70000 romans et pièces de théâtre cotés au point de vue moral.Trivia: There is an actual St-Joachim, Quebec, located roughly thirty kilometres downriver from Quebec City, but it bears no resemblance to the town depicted in Bessette's novel.

Retranslating a Quebec ClassicThe Urquhart translation is also still in print.

Pastor Clough remarked more than once that his gravedigger showed little concern for the rituals of pre-burial; he even went so far as to doubt the man's confederacy with Christianity. John Evans was never seen inside the church. He remained for the most part a man unnoticed, passing his days digging deep holes and then refilling them upon the heads the town's deceased. Occasionally he would disappear; on those occasions he would be employed at other towns in the vicinity digging for their burials. No one had to tell him where or when his particular services were required. He just knew. The man had a nose for death. He could sniff its adolescent scent on the breeze and be gone in its direction before the bereaved could gather.All hints at the supernatural, bringing to mind Ray Bradbury's G.M. Dark (Something Wicked This Way Comes) and Stephen King's Leland Gaunt (Needful Things), mysterious outsiders who wreak havoc on small town America. I expected gravedigger Evans to be their Canadian cousin.

The woman had an uncanny knack. If she caught only so much as one word of private conversation, then the cat was out of the bag.As the novel progressed, I became less interested those living in Breery than I did the town as a whole. How did was it, I wondered, that a town of five hundred could support a hardware store and diner? How was it that everyone lived in comfort, despite the Great Depression? More than anything, I wondered how Breery was able to afford a full-time gravedigger.

The boy's breath billowed with the exertion of his haste. It was in his heart to consummate their earliest vague discussion. Since that first talk he'd been savouring with anticipation what he hoped the digger might tell him next. He hurried and was quickly upon the object of his haste.Forever 33 was declared a finalist in the $50,000 Seal Books First Novel Award.

|

| The Vengeful Heart Roberta Leigh [pseud Rita Lewin] Toronto: Harlequin, 1970 |

His love would be her weapon.

"You were lucky to marry me, weren't you?" Julia mocked. "But you'll never possess me, Nigel!"

The knowledge should have filled her with a sense of power. Power over a man she hated! Nigel Farnham's ruthless prosecution of her father had sent him to prison, where he died alone.

Julia had vowed to make Nigel pay; to destroy the lawyer's life the way he had destroyed her parents. And now she had to carry out her plan for revenge – no matter what the cost...Happy Valentine's Day!