The Translation of a Savage

Gilbert Parker

London: Methuen, [c.1897]

240 pages

I'm writing this after having spent several hours shovelling heavy slushy snow and stacking firewood. It may not be the best time – the mind is less than sharp and the body is tired – but I can't put off sharing my discovery of The Translation of a Savage, which is by far the most unpleasant and problematic novel I've ever read.

|

The Camden Democrat

6 October 1894 |

I mean discovery in a personal sense, of course;

The Translation of a Savage was a bestseller in Canada, Great Britain, and the United States.

Lippincott's Monthly Magazine devoted much of its June 1893 edition to publishing the novel in full. It was serialized in newspapers throughout the United States, and was thrice adapted by Hollywood. In the introduction provided for his 24-volume

Works, Parker remarks on the novel's "many friends – sufficiently established by the very large sale it has had in cheap editions."

Sadly, those friends are long dead, and there is precious little evidence the novel is being read today.*

The Translation of a Savage begins in uninteresting fashion as yet another tale of the Canadian North. Frank Armour is a son of English privilege come to "Hudson Bay country" to further his fortune through mining. In doing so, he leaves behind his betrothed, beautiful Miss Julia Sherwood. The Armour parents aren't terribly keen on favourite son Frank's fiancée because she doesn't come from money; they'd much rather he marry Lady Agnes Martling, who "had long

cared for him, and was most happily endowed with wealth and good looks." In their son's absence, mama and papa conspire to prevent the union.

Easily done! They invite Miss Sherwood to Greyhope, their Herefordshire home, then bring in young Lord Haldwell, and Bob's your uncle!

It's quite a blow to Frank, who receives his "Dear John" letter after reading about Julia and Hopewell's wedding in the society pages. He knows to blame his parents for the broken engagement, though as I've suggested, they didn't put in much effort. Nevertheless, brandy in his belly and revenge in his heart, he looks to "bring down the pride of his family" by marrying Lali, daughter of Chief Eye-of-the-Moon. After a brief honeymoon, the bride is dispatched to Greyhope in buckskin dress.

|

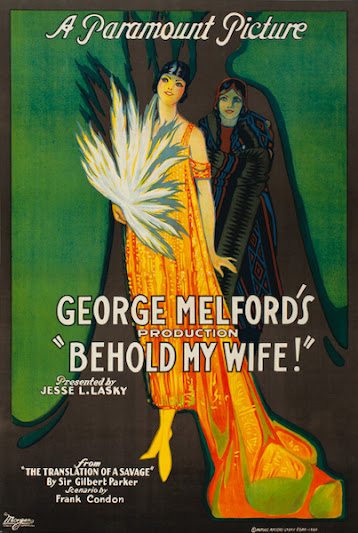

| Lali, as portrayed by Mabel Julienne Scott, in Behold My Wife!, the 1920 Hollywood adaptation of The Translation of a Savage. |

Lali's arrival in England is preceded by a well-crafted letter in which Frank acknowledges his parents' anxiousness that he wed "acceptably." He takes pains to note that Lali is of "the oldest aristocracy, in America." Because they'd wished him to marry wealth, he has sent them a wife rich in virtues, "native, unspoiled virtues." Frank trusts that they will take his bride to their hearts and cherish her, ever aware of their firm principles of honour. They will be kind to Lali until his return, "to share the affection which he was sure would be given to her."

The letter lands in the second of the novel's fifteen chapters. Twenty-first-century readers familiar with Victorian literature and mores will anticipate the reaction. I did, but was taken aback by a racial epithet entirely new to me. As I'm not one for censorship, I present it here. If you want to read it, click on the image below.

Richard Armour is the hero of this story. Frank's younger older-looking bookish brother, "not strong on his pins," has devoted his life to helping pensioners, the poor, and the infirm. Lali's acceptance at Hopewell is all Richard's doing. He is her defender. With gentle touch, he manipulates his family to her side, and provides the guidance she needs in navigating English society.

Lali is the heroine. A young bride – her age is never disclosed – she wed Frank for love. Because that love is not blind, Lali quickly comes to recognize the awful truth behind her marriage.

Frank is the villain. After marrying Lali, he remains in Canada, and never so much as writes. His ventures are unsuccessful, in large part because his wife's people come to question what has become of Lali. Frank's people – by which I mean his family – do not trust his judgement. By the time Lali gives birth to a son, seven or so months after arriving at Hopewell, she has won over the Armour family. They recognize how badly she has been treated, and so respect her wishes that they keep the child's existence a secret.

Four years pass before Frank's return, during which Lali has adapted to her new surroundings. The woman he encounters in the halls of Greyhope is very different than the "heathen" he married.

|

Lali (Mabel Julienne Scott) and Frank (Milton Sills) are reunited in

Behold My Wife! (1920). |

That word – "heathen" – is the used by Lali at the novel's climax, in which she is pushed to confront her husband:

Years of indignation were at work in her. “I have had

a home,” she said, in a low, thrilling voice, — “a

good home; but what did that cost you? Not

one honest sentiment of pity, kindness, or solicitude. You clothed me, fed me, abandoned

me, as — how can one say it? Do I not know,

if coming back you had found me as you

expected to find me, what the result would have

been? Do I not know? You would have

endured me if I did not thrust myself upon you,

for you have after all a sense of legal duty, a

kind of stubborn honour. But you would have made my life such that some day one or both of

us would have died suddenly. For” — she looked

him with a hot clearness in the eyes — “for

there is just so much that a woman can bear.

I wish this talk had not come now, but, since it

has come, it is better to speak plainly. You see,

you misunderstand. A heathen has a heart as

another — has a life to be spoiled or made happy

as another. Had there been one honest passion

in your treatment of me — in your marrying me —

there would be something on which to base

mutual respect, which is more or less necessary

when one is expected to love. But — but I will

not speak more of it, for it chokes me, the insult

to me, not as I was, but as I am. Then it would

probably have driven me mad, if I had known;

now it eats into my life like rust!"

Ultimately, of course, "heathen" is Parker's word, as is the measure of what a woman can bear. Lali existed only in his imagination, and remains with us today solely through the printed page.**

Frank tries to make amends, though His motivation is unclear. Is it, as Lali suggests, a sense of duty and a stubborn kind of honour? Might it have something to do with her "translation" to a woman who has been accepted by Society? Or is it simply because the two have a son? I have no answer, though will direct the curious to an associated theological question (below).

The very definition of a forgotten novel; The Canadian Encyclopedia, The Encyclopedia of Canadian Literature, The Oxford Companion to Canadian Literature, and The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature don't so much as mention The Translation of a Savage. This old Canadian Studies, English, and History major always saw it as just another of the dozens of Parker titles. I knew nothing about the novel, but feel I should have been made aware.

The Translation of a Savage begins as a story of the Canadian North. Aforementioned racial epithet aside, its attitudes and depictions of First Nations people are typical of Victorian literature; Lali's father, for example, is the very example of the "noble savage." What sets the novel apart is Lali and her translation.

She receives love in the Old World, in the main from the Amour family, making life sufferable, but her story is terrible. The entire story is terrible. Lali would like to return to Hudson Bay country, but feels she is too much changed. The novel's final sentences hint at reconciliation with Frank, but it is in no way a happy ending.

After all the time that has passed since reading those final words – some of it spent shovelling snow and stacking firewood – I'm still not sure what to think. What I can say, without hesitation, is that The Translation of a Savage should be read, studied, and discussed.

* Highly unscientific I know, but I do note that Goodreads features one lone readers' rating (one star), whereas Parker's The Right of Way has fourteen (3.36 stars average).

** I acknowledge that variations of Lali have appeared throughout the years on the silver screen – 1913, 1920, and 1934, to be precise – but Parker had no input in those depictions.

The subject of a future post.

Trivia: Frank receives news of Julia's marriage at Fort Charles – twice "Fort St. Charles" – a Hudson Bay Company outpost not far from the Kimash Hills and the White Valley. All exist only in Parker's fiction, most notably Pierre and His People (1894) and A Romany of the Snows (1898).

Interestingly, in 1907 poet Harmony Twichwell submitted an outline of an opera titled 'Kimash Hills' to her future husband Charles Ives.

Not trivia: In The Works of Gilbert Parker the author writes that the story "had a basis of fact; the main incident was true. It

happened, however, in Michigan rather than in Canada; but

I placed the incident in Canada where it was just as true to the

life."

A theological question (spoiler): The novel ends suddenly with a contrived crise, after which we learn that Lali accepts "without

demur her husband's tale of love for her." The suggestion is that this brings the couple together. Then come the last two ssentences:

Yet, as if to remind him of the wrong he had

done. Heaven never granted Frank Armour

another child.

If this is God's punishment is He not also punishing Lali?

Criticism: In his Works introduction, Parker notes that the novel was well-received. Despite the author's misgivings, Sir Clement Konloch-Cooke was eager to publish it in The English Illustrated Magazine. This was followed by enthusiasm from an unexpected source:

The judgment

of the press was favourable, – highly so – and I was as much surprised as pleased when Mr. George Moore, in the Hogarth Club

one night, in 1894, said to me: “There is a really remarkable

play in that book of yours, The Translation of a Savage.” I

had not thought up to that time that my work was of the kind

which would appeal to George Moore, but he was always making discoveries.

Object and Access: The novel made its debut in the June 1893 edition of Lippincott's Monthly Magazine. My copy was purchased online late last year from a French bookseller. Price: US$14.65. It was advertised as the 1894 first British edition; indeed the title page suggests as much, but the novel itself is followed by a 40-page catalogue of Methuen titles dated March 1897. Included are seven Parker novels and Robert Barr's disappointing In the Midst of Alarms.

Je ne regrette rien.

This copy, the copy that now rests in my Upper Canadian home, once belonged to Parker's fellow Tory Sir Henry Drummond Wolff, who from 1892 to 1900 was British Ambassador to Spain.

Sir Henry was also the father of prolific novelist Anne Cleeve, author of

The Woman Who Wouldn't (1895), written in response to Grant Allen's

The Woman Who Did (1895).

In its first three decades,

The Translation of a Savage went through plenty of editions from plenty of publishers. I'm betting most used booksellers can't be bothered listing them for sale online. Of those who have, the least expensive – an undated Nelson at £2.80 – is offered by a UK bookseller. The most expensive is a cocked copy of Appleton's 1893 American first edition at US$75.00.

Those with an aversion to previously-owned books – I knew one such person – will see that both Indigo and Amazon sell this Esprios World Classics print on demand edition.

The photograph used on the cover was taken in 1902 at the Warm Springs Indian Reservation, Wasco County, Oregon, adding further insult.

Related posts: