A Daughter of Witches: A Romance

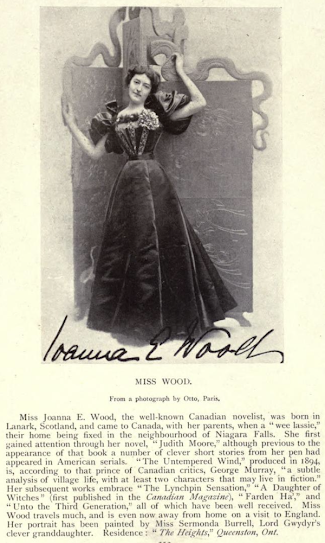

Joanna E. Wood

[n.p.]: Luminosity, [n.d.]

241 pagesOf all the books read these past twelve months, not one haunts so much as Joanna E. Wood's 1894 debut novel The Untempered Wind. It tells the story of Myron Holder, an unwed mother who dares raise a child in Jamestown, a provincial village located somewhere in the Niagara Region. To this reader, it is earliest example of Southern Ontario Gothic, holding every characteristic of the sub-genre; Protestant morality and hypocrisy are paramount.

|

Types of Canadian Women

Henry J. Morgan, ed.

Toronto: William Briggs, 1903 |

A Daughter of Witches, is Wood's third novel. It's set south of the border in the New England community of Dole, but make no mistake, this is Wood Country. The accents may differ, but the townsfolk of Dole are every bit as narrow-minded-minded and judgemental as those of Jamestown.

Dole is something akin to a closed community. Its families go back generations, stay put, and generally keep to themselves (see below). From time to time, someone will leave the village and strike out for Boston, the most recent being young Len Simpson.

And now he's dead... so there you go.

Old Lansing has this to say:

"Yes the buryin's to-morrow, and it seems Len

was terrible well thought of amongst the play-actin'

folk, and they've sent up a hull load of flowers along

with the body, and there's a depitation comin' to-morrow to the buryin' and they say there's considerable money comin' to Len and of course his

father'll get it. I don't know if he'll buy that spring

medder of Mr. Ellis, or if he'll pay the mortgage

on the old place, but anyhow it'll be a big lift to him."

No one in Dole is the least bit curious as to how Len acquired such wealth. The general consensus is that he was a disgrace to his family. It's whispered that he drank.

News of Len Simpson's death coincides with the arrival of Sidney Martin, son of Sid Martin. Decades earlier, Sid left Dole to make a life for himself in Boston. He did something there, no one knows just what, but it is known that he married a woman from a moneyed family.

Sidney Martin's mother and father are now dead. Frail and pale, their son isn't looking too good himself. His countenance and weak physique contrast with raven-haired Vashti Lansing, whose Amazonian beauty and strength – she's first seen wrestling a runaway horse – captures the young man's heart.

|

| The Canadian Bookseller, August 1900 |

Sidney falls hard for Vashti, but Vashti is in love with her cousin Lansing "Lanty" Lansing. Lanty loves another cousin, fair Mabella Lansing. Cousin Mabella returns his love.

The author passes no judgement on this bizarre love triangle, though she does torture Vashti in having her witness the moment in which her two cousins declare their love for one another.

Vashti is the central character in this romance, yet she is one of least realized characters. I believe this is intentional. Wood describes Vashti as acting on instinct; her will is not entirely her own:

Long ago they

had burned one of her forbears as a witch-woman.

They said she caused her spirit to enter into her

victims and commit crimes, crimes which were naively

calculated to tend to the worldly advantage of the

witch. Vashti thought of her martyred ancestress

often; she herself sometimes felt a weird sensation

as of illimitable will power, as of an intelligence apart

from her normal mind, an intelligence which wormed

out the secrets of those about her, and made the

fixed regard of her large full eyes terrible.

Sidney Martin is so smitten, yet so blind, that he proposes marriage to Vashti on the very same spot Lanty and Mabella become engaged. Vashti's acceptance, which came as something of a surprise to this reader, comes with two conditions, the first being that once married they will live in Dole. The second condition, odd in the extreme, is that Sidney, an agnostic, will become an ordained minister so as to take over from old Mr Didymus, the village pastor.

What is Vashti up to? She does not know herself.

Sidney leaves Dole to study theology in Boston, returning years later as Didymus is dying. The elderly preacher's final act is to marry fiancé and fiancée.

As the bride had long intended, the newlyweds move into the parsonage and Sidney takes over the ministry. If anything, he is more popular than his predecessor. Sidney's sermons, focusing on the majesty of the natural world, go over well in what is essentially a farming community. This is not to suggest that Sidney and Vashti are immune to town gossip.

As the preacher's wife, Vashti draws resentment in lording over the local ladies, attending their weekly sewing circle in gowns made in Boston. Then there's cousin Lanty – secret object of her affection – who has fallen into drink. Harsh words are spoken of Ann Serrup. "Left at thirteen the only sister

among four drunken brothers much older than herself," like Myron Holder in

The Untempered Wind, Ann is an unwed mother. Might Lanty be the father?

All this poisonous talk exhausts the patience of Temperance Tribbey, Old Lansing's housekeeper. In one of the novel's many memorable scenes, she takes down Mrs Abiron Ranger:

Temperance spoke with a knowledge of her subject

which gave play to all the eloquence she was capable

of; she discussed and disposed of Mrs. Ranger's

forbears even to the third generation, and when

she allowed herself finally to speak of Mrs. Ranger

in person, she expressed herself with a freedom and

decision which could only have been the result of

settled opinion.

"As for your tongue, Mrs. Ranger, to my mind,

it's a deal like a snake's tail it will keep on moving

after the rest of you is dead."

Vashti's instinct brings what I believe is intended as the climax. My uncertainty has to do with the scene being nowhere near as memorable as others. It should haunt, but it does not haunt.

And so, the spoiler:

One Sunday morning, Sidney takes to the pulpit and delivers a sermon unlike any other. More brimstone than pastural, he admonishes his parishioners, pointing out their duplicity, dishonesty, deceit, and deception. Sidney repeats town gossip going back decades, but his words are not his own; they belong to Vashti, a daughter of witches.

Not a spoiler:

Vashti's fate is not deserved, nor is Wood's fate as a forgotten novelist.

Bloomer:

"Lanty will take it terribly hard," said the old

man musingly. "He and Len Simpson ran together

always till Len went off, and Lanty never took up

with anyone else like he did with Len."

Object and Access: A Daughter of Witches first appeared serialized in the Canadian Magazine (November 1898 - October 1899). In 1900, Gage (Canada) and Hurst & Blackett (England) published the novel in book form. I've yet to find a copy of either edition for sale, and so bought this print-on-demand edition.

The Gage edition can be read online here at the Internet Archive.

Related posts: