Quebec in Revolt

Herman Buller

Toronto: Swan, 1966

352 pages

The cover has all the look of a 1960s polemic, but Quebec in Revolt is in fact a historical novel. Its key characters are depicted on the title pages:

Herman Buller

Toronto: Swan, 1966

352 pages

The cover has all the look of a 1960s polemic, but Quebec in Revolt is in fact a historical novel. Its key characters are depicted on the title pages:

At far left is Joseph Guibord, he of the Guibord Affair.

The Guibord Affair?

Like Gordon Sinclair, one of twelve columnists and critics quoted on the back cover, the Guibord Affair meant nothing to me.

It most certainly didn't feature in the textbooks I was assigned in school. This is a shame because the Guibord Affair would've challenged classmates who complained that Canadian history was boring.

Here's what happened:

In 1844, Montreal typographer Joseph Guibord helped found the Institut canadien. An association dedicated to the principles of liberalism, its library included titles prohibited by the Roman Catholic Index – the Index Librorum Prohibitoru. These volumes, combined with the Institut's cultural and political activities, drew the condemnation of Ignace Bourget, the Roman Catholic Bishop of Montreal. In July 1869, Bourget issued a decree depriving members of the sacraments. Guibord died four months later.

Here's what happened next:

Guibord's body was transported to a plot he'd purchased at Montreal's Catholic Notre-Dame-des-Neiges Cemetery, only to be refused burial by the Church. The remains found a temporary resting place at the Protestant Mount Royal Cemetery, while friend and lawyer Joseph Doutre brought a lawsuit on behalf of the widow Guibord. In 1874, after the initial court case and a series of appeals, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council ordered the burial. In response, Bourget deconsecrated Guibord's plot.

The second attempt at interment, on 2 September 1875, began at Mount Royal Cemetery:

At Notre-Dame-des-Neiges, a violent mob attacked, forcing a retreat to Mount Royal.

The third attempt, on 16 November, was accompanied by a military escort of over 1200 men. Guibord's coffin was encased in concrete so as to protect his body from vandals.

The third attempt, on 16 November, was accompanied by a military escort of over 1200 men. Guibord's coffin was encased in concrete so as to protect his body from vandals.

The sorry "Guibord Affair" spans the second half of the novel. The focus of the first half is the man himself. Young Guibord woos and weds Henriette Brown, the smallpox-scared orphaned daughter of a poor shoemaker. He moves up the ranks within Louis Perrault & Co, the printing firm in which he'd worked since a boy, eventually becoming manager of the entire operation.

|

| Louis Perrault & Co, c.1869 |

Henriette and husband come to be joined by Della, the daughter of one of her distant Irish cousins. Poor girl, Della was part of the exodus brought on by the Potato Famine. Her father and lone sibling having died whilst crossing the Atlantic – mother soon to follow – she clings to life in one of the "pestilential sheds" built for accommodate diseased immigrants. The most dramatic scene in the novel has Joseph defying authority by lifting he girl from her sickbed and carrying her home.

"Skin and bone had given way to flesh and curves," Della recovers and grows to become a headstrong young woman. Buller makes much of her breasts. Ever one to buck convention and authority, Della spurns marriage, has a lengthy sexual and intellectual relationship with journalist Arthur Buies, and ends up living openly with Joseph Doutre ("Josef" in the novel). Truly, a liberated woman; remarkable for her time.

"Skin and bone had given way to flesh and curves," Della recovers and grows to become a headstrong young woman. Buller makes much of her breasts. Ever one to buck convention and authority, Della spurns marriage, has a lengthy sexual and intellectual relationship with journalist Arthur Buies, and ends up living openly with Joseph Doutre ("Josef" in the novel). Truly, a liberated woman; remarkable for her time.

I've yet to find evidence that Della existed.

Joseph Guibord's entry in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography informs that he and Henriette, a couple Buller twice describes as childless, had at least ten children. The entry for Joseph Doutre, whom the author portrays as a lifelong bachelor, records two marriages.

Joseph Guibord's entry in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography informs that he and Henriette, a couple Buller twice describes as childless, had at least ten children. The entry for Joseph Doutre, whom the author portrays as a lifelong bachelor, records two marriages.

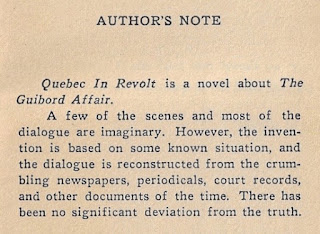

Were it not for the novel's Author's Note, pointing out that Guibord began his career working for John Lovell (not Louis Perrault), or that he was born on 31 March 1809 (not 1 April 1809), or that women didn't wear bustles in 1820s Montreal, might seem nit-picky.

The Swan paperback quotes Al Palmer, author of Montreal Confidential and Sugar Puss on Dorchester Street):

The Swan paperback quotes Al Palmer, author of Montreal Confidential and Sugar Puss on Dorchester Street):

In fact, what Palmer wrote is this:

|

| The Gazette, 19 November 1965 |

I expect there many more fabrications and errors in this novel and its packaging, but can't say for sure. Again, we didn't learn about the Guibord Affair in school.

About the author: Herman Buller joins Kenneth Orvis and Ernie Hollands as Dusty Bookcase jailbird authors. A lawyer, he rose to fame in the 'fifties as part of a baby-selling ring.

|

| The Gazette, 13 February 1954 |

Buller was arrested at Dorval Airport on 12 February 1954 whilst attempting to board a flight to Israel with his wife and in-laws. The worst of it all – according to the French-language press – was that the lawyer had placed babies born to unwed Catholic women with Jewish couples.

|

| La Patrie, 11 February 1954 |

Though Quebec in Revolt was published just eleven years after all this, not a single review mentioned of Buller's criminal past.

I hadn't heard of the Buller Affair (as I call it) until researching this novel, despite it having been dramatized in Le berceau des anges (2015) a five-part Series+ series. Buller (played by Lorne Bass) is mentioned twenty-two seconds into the trailer.

I hadn't heard of the Buller Affair (as I call it) until researching this novel, despite it having been dramatized in Le berceau des anges (2015) a five-part Series+ series. Buller (played by Lorne Bass) is mentioned twenty-two seconds into the trailer.

Fun fact: I read Quebec in Revolt during a recent stay at the Monastère des Augustines in Quebec City.

Object and Access: A bulky, well-read mass-market paperback, my copy was purchased for one dollar this past summer at an antiques/book store in Spencerville, Ontario.

Quebec in Revolt was first published in 1965 by Centennial Press. If the back cover is to be believed, McKenzie Porter of the Toronto Telegram describes that edition as a "Canadian best seller." I've yet to come across a copy.

Quebec in Revolt was first published in 1965 by Centennial Press. If the back cover is to be believed, McKenzie Porter of the Toronto Telegram describes that edition as a "Canadian best seller." I've yet to come across a copy.

As of this morning, seven copies of Quebec in Revolt are listed for sale online. At US$6.00, the least expensive is offered by Thiftbooks: "Unknown Binding. Condition: Fair. No Jacket. Readable copy. Pages may have considerable notes/highlighting," Take a chance! Who knows what will arrive!

There are two Swan copies at US$8.00 and US$12.45. Prices for the Centennial edition range from US$10.00 (sans jacket) to US$24.00.

Surprisingly, Quebec in Revolt enjoyed an Estonian translation: Ja mullaks ei pea sa saama... Google translates this as And you don't have to become soil...

There hasn't been a French translation.

Is it any wonder?

There hasn't been a French translation.

Is it any wonder?