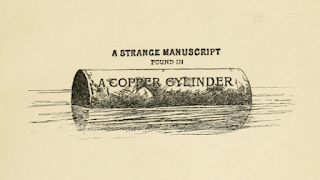

A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder

[James De Mille]

New York: Harper & Bros, 1888

306 pages

Forty years ago this month, I sat on a beige fibreglass seat to begin my first course in Canadian literature. An evening class, it took place twice-weekly on the third-floor of Concordia's Norris Building. I was a young man back then, and had just enough energy after eight-hour shifts at Sam the Record Man.

The professor, John R. Sorfleet, assigned four novels:

James de Mille - A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder (1888)

Charles G.D. Roberts - The Heart of the Ancient Wood (1896)

Thomas H. Raddall - The Nymph and the Lamp (1950)

Brian Moore - The Luck of Ginger Coffey (1960)

These were covered in chronological order. I liked each more than the last. The Luck of Ginger Coffey is the only title I wholeheartedly recommend, which is not to suggest that I didn't find something of interest in the others.

The earliest, A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder, intrigued because it overlapped with the lost world fantasies I'd read in adolescence. Here I cast my mind back to Edgar Rice Burroughs' Pellucidar, my parents' copy of James Hilton's Lost Horizon, and of course, Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World.

De Mille's novel begins aboard the yacht Falcon, property of lethargic Lord Featherstone. The poor man has tired of England and so invites three similarly bored gentlemen of privilege to accompany him on a winter cruise. February finds Featherstone and guests at sea somewhere east of the Medeira Islands, where they come across the titular cylinder bobbing in becalmed waters. Half-hearted attempts are made at opening the thing, until Melick, the most energetic of the quartet, appears with an axe.

As might be expected – the title is a bit of a spoiler – a strange manuscript is found within. Its author presents himself as Adam More, an Englishman who, having been carried by "a series

of incredible events to a land from which escape is as impossible

as from the grave," sent forth the container "in the hope that the ocean currents may bear it within the

reach of civilized man."

More would have every right to feel disappointed.

Featherstone and company, while civilized, are not the best civilization has to offer. In the days following the discovery, they lounge about the Falcon taking turns reading the manuscript aloud, commenting on the text, and speculating as to its veracity.

More writes that he was a mate on the Trevelyan, a ship chartered by the British Government to transport convicts to Van Dieman's Land. This in itself sounds fascinating, but he skips by it all to begin with the return voyage. Inclement weather forces the Trevelyan south into uncharted waters "within fifteen hundred miles of the South Pole,

and far within that impenetrable icy barrier which, in 1773, had arrested the progress of Captain Cook."

No one aboard the Trevelyan is particularly concerned – the sea is calm and the skies clear – and no objections are raised when More and fellow crew member Agnew take a boat to hunt seals. Fate intervenes when the weather suddenly turns. In something of a panic, the pair make for their ship, but efforts prove no match for the sea. They are at its mercy, resigned to drifting with the current, expecting slow death. And yet, they do find land, "a vast and

drear accumulation of lava blocks of every imaginable

shape, without a trace of vegetation—uninhabited, uninhabitable." A corpse lies not far from the shore:

The clothes were those of a European and a sailor;

the frame was emaciated and dried up, till it looked like

a skeleton; the face was blackened and all withered,

and the bony hands were clinched tight. It was evidently some sailor who had suffered shipwreck in these

frightful solitudes, and had drifted here to starve to

death in this appalling wilderness. It was a sight which seemed ominous of our own fate, and Agnew’s

boasted hope, which had so long upheld him, now sank

down into a despair as deep as my own. What room

was there now for hope, or how could we expect any

other fate than this?

More and Agnew provide a Christian burial and return to their boat hoping, but not expecting, to be carried to a better place. Whether they find one is a matter of opinion. The pair pass through a channel that appears to have been formed by two active volcanoes, after which they encounter humans More describes as "animated mummies." They seem nice, until they reveal themselves as cannibals. Hungry eyes are cast on Agnew. He's killed and More escapes.

A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder is not a Hollow Earth novel, though inattentive readers have described it as such. More's boat enters a sea within a massive cavern, where he encounters a monster of some sort and fires a shot to scare it off.

The boat continues to drift, emerging on a greater open sea. It's at this point – 53 pages in – that the real adventure begins.

Here More encounters the Kosekin who, despite their small stature, appear much healthier than the animated mummies who killed and consumed his friend Agnew. They're also extremely generous, ever eager to give More whatever his heart desires. He is soon introduced to Almah, a fair beauty who, like himself, is not of their kind.

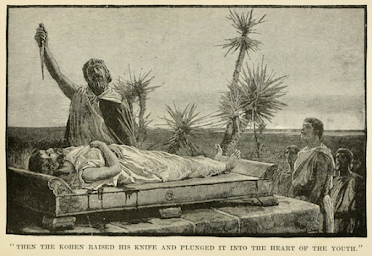

Through Almah, More learns the language, customs, and culture of the Kosekin and their topsy-turvy polar world. They are a people who crave darkness and shun light. Self-sacrifice serves as the shell surrounding their core belief, so that they look to rid themselves of wealth and influence. The least is the most venerated. The local Kohen, whom More comes to know best of the Kosekin, shares a sad story:

"I was born," said he, "in the most enviable of positions. My father and mother were among the poorest

in the land. Both died when I was a child, and I never

saw them. I grew up in the open fields and public

caverns, along with the most esteemed paupers. But,

unfortunately for me, there was something wanting in

my natural disposition. I loved death, of course, and

poverty, too, very strongly; but I did not have that

eager and energetic passion which is so desirable, nor

was I watchful enough over my blessed estate of poverty. Surrounded as I was by those who were only too

ready to take advantage of my ignorance or want of

vigilance, I soon fell into evil ways, and gradually, in

spite of myself, I found wealth pouring in upon me.

Designing men succeeded in winning my consent to receive their possessions; and so I gradually fell away

from that lofty position in which I was born. I grew

richer and richer. My friends warned me, but in vain.

I was too weak to resist; in fact, I lacked moral fibre,

and had never learned how to say 'No.' So I went on,

descending lower and lower in the scale of being. I became a capitalist, an Athon, a general officer, and finally

Kohen."

Again, 'tis sad, but the Kohen's own weakness is to blame. He displays greater strength when confronting his own mortality. Like all Kosekin, the Kohen longs for the day when his life will end. His people refer to Death as the "King of Joy." Almah does her best to explain to a disbelieving More:

"Here," said she, "no one understands what it is to

fear death. They all love it and long for it; but everyone wishes above all to die for others. This is their

highest blessing. To die a natural death in bed is

avoided if possible."

The Kohen tells the story of an Athon who had led a failed attack on a creature in which all were killed save himself. For this, he was honoured:

“Is it not the same with you? Have you not told me incredible things about your people, among which there were a few that seemed natural and intelligible? Among these was your system of honoring above all men those who procure the death of the largest number. You, with your pretended fear of death, wish to meet it in battle as eagerly as we do, and your most renowned men are those who have sent most to death.”

A Strange Manuscript in a Copper Cylinder shares something with Burroughs in that adventure, prehistoric beasts, and a love interest figure. What sets it apart is the quality of writing; De Mille's is by far the superior. No doubt some readers – my twelve-year-old self would've been one – will be irked by Lord Featherstone and his three guests, who see in More's manuscript an opportunity to philosophize and expound theories on linguistics, geography, and palaeontology. Oxenden, the quietest of the group, speaks up providing the most fascinating passages in remarking on the similarities in Kosekin, Christian, Jewish, Buddhist, and Hindu beliefs.

Melick alone expresses skepticism in More's story, dismissing the manuscript as a bad romance: "This writer is tawdry; he has the worst vices of the sensational school – he shows everywhere marks of haste, gross carelessness and universal feebleness." Unflattering comparisons to DeFoe and Swift are drawn.

A Strange Manuscript in a Copper Cylinder demonstrates none of the things Melick describes. Forty years later, I have no hesitation in recommending the novel; it is richer and more rewarding than I remembered.

Wish I'd known what my thoughts were on first reading. There may be a paper written for Prof Sorfleet's class in the crawlspace beneath our living room.

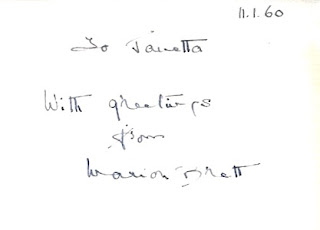

Object and Access: All evidence suggests that A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder was written in the 1865 and 1866. It was first published posthumously and anonymously in the pages of Harper's Weekly (7 Jan 1888 - 12 May 1888). My copy, a first edition, features nineteen plates by American Gilbert Gaul. The copy I read as a student was #68 in the New Canadian Library (1969). I still have it today, along with the Carleton University Press Centre for Editing Early Canadian Texts edition (1986). Neither was consulted in writing this review, but only because they're in that damn crawlspace.

The NCL edition is out of print, but the Centre for Editing Early Canadian Texts edition remains available, now through McGill-Queen's University Press. It has since been joined by another scholarly edition from Broadview Press (2011).

Used copies of are easily found online. Prices for the Harper & Bros first edition range between US$65 and US$400. Condition is a factor, but not as much as one might assume. The 1888 Chatto & Windus British first (below) tends to be a bit more dear.

Translations are few and relatively recent: Italian (Lo strano manoscritto trovato in un cilindro di rame; 2015) and Hindi (

एक तांबा सिलेंडर में पाया एक अजीब पांडुलिपि, 2019).