Satan as Lightning

Basil King

New York: Harper, 1929

280 pages

Basil King

New York: Harper, 1929

280 pages

Basil King is the only Canadian to have topped the year-end list of bestselling novels in the United States. He accomplished this in 1909 with The Inner Shrine and came close to doing the same the following year with The Wild Olive.

Satan as Lightning came later – so much later that its author was dead.

Satan as Lightning came later – so much later that its author was dead.

|

| William Benjamin Basil King 26 February 1859, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island - 22 June 1928, Cambridge, Massachusetts RIP |

King's flawed hero is John Owen "Nod" Hesketh. The son of a prominent New York City Episcopal minister and precentor, Nod has been able to get away with a lot in his twenty-nine years. Consider the time bosom friend Edward Wrigley "Wrig" Coppard altered a two-dollar cheque to read "two hundred dollars." Nod and Wrig used their ill-gotten gains to shower girls with gifts and – ahem – "give them money." The forgery was eventually discovered, but as the cheque was issued by Wrig's father, wealthy businessman William Coppard, the two chums weren't brought before the law.

Sons of privilege – obviously – both Nod and Wrig attended schools of higher learning. After graduation, Rev Hesketh and Mr Coppard pooled funds to buy their boys a garage.

A garage?

The purchase makes no sense, though it does play an important role in the backstory. After their first year in business, Nod and Wrig found themselves two thousand dollars in debt. William Coppard wrote a cheque for nine dollars – something to do with the balance owing on a church organ – which Rev Hesketh gave to his son for deposit. On the way to the bank, Nod handed the cheque to Wrig, who then altered the amount to nine hundred. Nod used his half of the money to pay the garage's creditor; Wrig kept his half for himself. When caught, the reverend's son fessed up; not so, the rich man's son. Wrig feigns ignorance, and so the full weight lands on Nod. Rev Hesketh is of the belief that his son would do well by paying the penalty for his crime.

Call it tough love.

After serving a sentence of three years and nine months, Nod emerges from fictional Bitterwell Prison a changed man. No longer "devilish," the clergyman's son is intent on doing good, which includes paying off debts to former garage employee Tiddy Epps. Nod does not return to the Hesketh family home for fear of causing embarrassment. He lodges instead with the Bird family in a hovel not far from Gracie Mansion. Danny Bird, an accomplished pickpocket, is a friend met in prison. Wise Katy Bird, Danny's unattractive "lame" sister shares the abode, as does the matriarch, Mrs Bird. Mr Bird died some years earlier in the electric chair.

Call it tough love.

After serving a sentence of three years and nine months, Nod emerges from fictional Bitterwell Prison a changed man. No longer "devilish," the clergyman's son is intent on doing good, which includes paying off debts to former garage employee Tiddy Epps. Nod does not return to the Hesketh family home for fear of causing embarrassment. He lodges instead with the Bird family in a hovel not far from Gracie Mansion. Danny Bird, an accomplished pickpocket, is a friend met in prison. Wise Katy Bird, Danny's unattractive "lame" sister shares the abode, as does the matriarch, Mrs Bird. Mr Bird died some years earlier in the electric chair.

The ex-con's new life is modest with modest expectations, save one: Nod is intent on destroying former bosom friend Wrig Coppard. "I want other people to find out what he is," Nod tells Katy.

Tension is heightened with the introduction of beautiful Blandina Vandertyl – named after the the patron saint of those falsely accused of cannibalism – whose secret engagement to Nod ended when he was convicted. On the rebound, she married Walter Frankland, who was killed in the Château-Thierry salient. Just as well, Blandina knows she would've grown bored with him. Walter was too good and she has a thing for bad boys. The wealthy war widow is now being pursued by none other than Wrig Coppard.

In his time, Basil King was known for his ability to weave a complex plot, but that talent isn't much in evidence here. This novel trods a fairly straight path with few obstacles. The conflict between Nod and Wrig never takes place because Nod finds religion – not through his father's church, rather at an ecumenical weekly gathering known as the Sinners Conference.

|

| The novel's epigraphs. |

Basil King's spiritual journey was every bit as unconventional. An Anglican clergyman, he served as rector of St. Luke's Pro-Cathedral (Halifax, Nova Scotia) and Christ Church (Cambridge, Massachusetts), eventually resigning from the ministry due to failing eyesight and ill-health. During the Great War, King became interested in spiritualism, The Abolishing of Death (1919) being his clearest statement on the matter. Supernatural elements feature in much of his fiction, most notably in the novella Going West (1919), the novel The Empty Sack (1921), and in his script for the by all accounts great lost silent film Earthbound (1920).

Of the ten King novel's I've read to date, Satan as Lightning seems the most personal. Its plot is slowed and dulled by discourse on religion and Nod's writings about prison, punishment, reform, and redemption. but this Anglican Church of Canada congregant was more than satisfied. That said, as with Sunday sermons, I was happy when it was over.

Trivia: Though the place of worship is not mentioned by name, Nod's father, Rev Hesketh, serves at New York's St John the Devine.

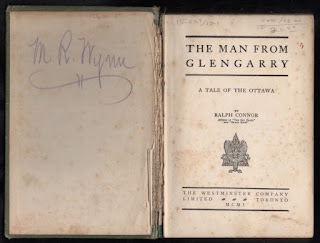

Coincidence: Satan as Lightning follows Ralph Connor's Corporal Cameron of the North West as the second novel I've read this year in which a young man finds himself in hot water over an altered cheque.

Was the crime really so common?

Trivia: This is the first King novel I've read to include a character from the author's home province: "Effie, a Scotch-Canadian from Prince Edward Island."

Other 1929 titles covered at the Dusty Bookcase:

Object and Access: A green hardcover, my copy lacks the dust jacket. It was purchased for six dollars at a failing London, Ontario bookstore. Marked down from $45.95.

All of three copies are listed for sale online, the cheapest being a copy – lacking jacket – at US$4.95. The other two, both of which have jackets, are offered at US$119.95 and US$125.00.

Take your pick.

The Retired Reverend King on the Abolishing of Death

Reverend King's Great War Novelette

The Great Canadian Post-Great-War Novel?

The Mission of Sex: Canadians, Do Your Duty!

Basil King's Silent Unseen World

Reverend King's Great War Novelette

The Great Canadian Post-Great-War Novel?

The Mission of Sex: Canadians, Do Your Duty!

Basil King's Silent Unseen World