The House in Brook Street

Ronald Cocking

London: Hurst & Blackett [1949]

Wives who wish their husbands to fall asleep at a reasonable hour should not allow them to take this title to bed; it is one of the 'to be read at a sitting' variety, and liable to bring about marital crisis.

– Bruce Graeme, jacket copy for The House in Brook Street

Started in bed, moved to an armchair and ended up on the living room couch. I fell asleep several times. All in all it was very disappointing. I'm ashamed to say I paid for it.

My third Cocking,

The House in Brook Street opens at Washington's Hotel Statler on the evening of V-J Day. Our hero and narrator, Inspector George Crawley of Scotland Yard, emerges from an elevator; that it isn't referred to as a "lift" is the novel's first and greatest surprise. George has been in the United States for three years, on loan to the FBI in its battle against wartime counterfeiting and the illegal transfer of bonds. Over a celebratory drink, G-Man pal Barney asks about future plans.

"What'll you do now? Go back to England, I suppose?"

"I suppose."

George isn't what you'd call a man of action, which may explain why he's never responded to G-Gal Norma Jean Travers' flirtations. A week after V-J Day she tries one last time, sitting on the corner of his desk, "one nylon leg crossed over the other," before giving up and seeing George off on the train that will take him to New York, the

Queen Mary and, eventually, dear old London.

Aboard train, a beautiful blonde named Brenda Walsh asks to share his private compartment. He watches as she fiddles with her purse, and then their coffee cups. "I began to feel nervous," reports George. The coffee tastes bitter. His final thought before losing consciousness: "I had fallen for the oldest trick in the world."

George is revived by a porter – "My, my sah! You sho' do sleep heavy!" – to find that the compartment has been ransacked. Though he recognizes that someone at the Bureau has leaked his itinerary, George proceeds as planned, checking into the hotel at which he has a reservation.

Wouldn't want to lose that deposit.

George sees that he's being trailed by a cream-coloured 1942 Chrysler, but that doesn't prevent him from stopping in on his pal Lou Rogers, a captain in the NYPD. Lou reminds George that he promised to give him a glossy of Scotland Yard. After that, it's off to a penthouse overlooking Central Park, where Jacob B. Rand – "

The Rand! Rand's First National Bank of New York!" – thanks him for catching a counterfeiter, then drones on about his enthusiasm for something called the Society of the Friends of Peace. Rand sends George back to the hotel in a cream-coloured 1942 Chrysler, something our hero dismisses as an "odd coincidence." His room has been ransacked.

The next day, aboard the

Queen Mary, George picks up a newspaper and reads this:

"That's what you have to get used to in America", George tells us. "Anything can happen there – and usually does."

It was at this point that I lost what little faith I had left in George. Nothing that followed caused me to reconsider – not even Scotland Yard's remarkable belief in their man.

Back in London, George is promoted to Chief Inspector and entrusted with security for the opening session of the United Nations General Assembly, scheduled to take place – as it did – on 10 January 1946 in London. Barney and Norma Jean arrive in town to ensure the safety of the American delegates. Good thing, too, because their English friend proves himself entirely inept. Twice he's lured to meet strangers who offer undisclosed information, twice he's warned that the meeting is suspicious, and twice he's ambushed. His worst beating comes after Brenda Walsh, the very same woman who slipped the Mickey Finn on the Washington-New York train, asks to meet him in Place Pigalle:

"The Place Piguelle!" I said."That's a hell of a place to meet anybody."

"I know," she said, "but we've got go to a house near there. I'll explain when I meet you."

"All right," I said. "I'll take your word for it. See you at eight."

After that particular ambush, George forgets to retrieve the gun that was knocked from his hand.

Cocking forgets, too.

The author's debut,

The House in Brook Street is set in an odd world in which a policeman specializing in counterfeiting and financial fraud is tasked with ensuring the safety of hundreds of the world's most important politicians, ambassadors and bureaucrats. George has no staff and meets with no one other than Barney and Norma Jean. He never visits Central Hall Westminster, at which the General Assembly is to take place.

At some point, George is reassigned. We don't know when exactly – he keeps it from us for a while – but I'm willing to accept his story. It seems that banker Jacob B. Rand and his Society of the Friends of Peace friends are up to something, and because George has met Rand... well, who better to figure things out? No one knows just what Rand and the SFP have in mind except that it's being cooked up in the Society's house on... er, in Brook Street, and will take place on the very day the General Assembly is to convene. Sadly, George proves himself to be just as ineffective as ever. Frustrating as it is for the reader, it does include this pretty great passage:

I once read in a book that one of the chief requirements of a novel was that it should have Dramatic Unity. Well, I suppose that in a piece of fiction you can organize things so that the action is smooth-flowing and that the bits and pieces all fuse together in a nice, complete whole.

My trouble is that I've got to set the facts down just as they happened (and anyway I'm a policeman, not a writer). So I've got to ruin the Dramatic Unity of the story by skipping three weeks or so. Why? Well, simply because the whole case came to a complete standstill.

A serious alcoholic, Barney is of no help. Norma Jean spends all her time cooking for the men, making pots of coffee and changing outfits. As the day of the General Assembly draws near, the trio are kidnapped by Rand. For no good reason, the banker tells them all about his plans for murdering foreign delegates. A forged document will convince the world that the orders came from Downing Street. World War Three will begin with a new Axis led by "fanatical Nazis in hiding in the Bavarian Alps."

That's Rand's plan, anyway.

Convinced that they have no hope of escape, George, Barney and Norma Jean while away the hours playing cards until, quite by chance, they're rescued.

Really. That's what happens. I didn't dream it.

Favourite sentence:

It was so obvious that the only excuse which I can make for not seeing it before is that I had a lot of things on my mind.

Trivia: The House in Brook Street follows

Jane Layhew's Rx for Murder as the second novel read in five months to feature "nigger in the woodpile", an expression I swear I'd never before encountered.

The novel's lone black character is the railway porter mentioned above. A helpful soul, the last we see him is when Crawley's train arrives in New York:

"We is pullin' out ob dis bay in two minutes, sah." He was looking at me curiously.

I looked around. Miraculously, my bags were packed and ready.

"That's fine," I said, "thanks a lot." I gave him five dollars and his shining black face split in a huge grin.

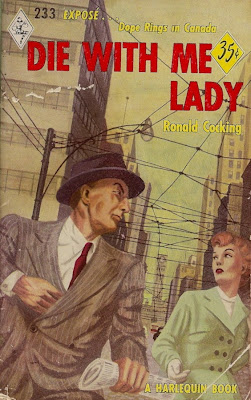

Object and Access: A compact 224 pages in rose-coloured boards. The cover illustration is uncredited.

Excited by the opening scenes of Cocking's Die With Me, Lady, in 2012 I purchased my copy for £35 from a bookseller in Winterton, Lincolnshire. The pages were uncut.

The rear flap announces Cocking's second novel,

High Tide is at Midnight (1950), which I read and

reviewed here two years ago. In turn, the

High Tide is at Midnight dust jacket reports that

The House in Brook Street has enjoyed three printings. Surprising. I see just one copy of

The House in Brook Street being offered for sale online. The UK bookseller provides this description: "Book Condition: Acceptable. Foxing/tanning to edges and/or ends. No dust jacket. Pages tanned. Staining/marking to cover. Staining/marking to pages/page edges. Wear/marking to cover." Price: £74.57.

It's not worth considering.

Not a trace in Canadian libraries, I'm afraid. American cousins will find one lonely copy at Boston University. My English cousins are served by Oxford University and the British Library.

Related posts: