Grant Allen

London: Chatto & Windus, 1901

317 pages

Roughly one-third of the way though Philistia, Herbert Le Breton prepares to ascend the Piz Margatsch

I was hoping he'd be killed in the attempt.

The death would be hard on his mother, of course, but then Lady Le Breton is accustomed to loss. Some years before, her husband, Sir Owen, perished in the Indian Mutiny, leaving her with three young boys and an unexceptional military pension. The widow soldiered on, raising her sons in a modest townhouse in an exclusive neighbourhood. Its address had everything to do with keeping up appearances.

Oxford men, together Herbert and Ernest form one half of a clique that includes mathematician Henry Oswald, a Fellow and Lecturer at Oriel College. The last in their group, the Reverend Arthur Berkley, curate of St Fredegond's, has first-floor rooms in the front quad of Magdalen.

All four men are close, but not nearly so that they know much about one another. No one is aware that Arthur is the son a poor shoemaker. Lady Le Breton's sons have some idea that Henry Oswald's parents are grocers in "the decayed and disfranchised borough of Calcombe

Pomeroy."

It goes without saying that class distinction and geography mean nothing to Ernest, whose heart is won by Edith Oswald, Henry's lone sibling.

Can you blame him? Edie is as intelligent and personable as she is pretty. And, though low on the social scale she's dedicated to the betterment of the less fortunate.

Ernest and Edith are a great match, but Herbert looks down on the couple. That he does has everything to do with my wish for his death on Piz Margatsch. You see, Henry too shares a relationship with a grocers' daughter: Selah Briggs. She knows him as "Herbert Walters." He's promised marriage, but has no intention of watching her walk down the aisle. In short, he's stringing her along.

Grant Allen's first novel, Philistia followed seven volumes of non-fiction, the earliest being Physiological Æsthetics (London: Henry S. King, 1877). In My First Book (London: Chatto & Windus, 1897), Allen writes:

I wasn't born a novelist, I was only made one. Philosophy and science were the first loves of my youth. I dropped into romance as many men drop into drink, or opium-eating, or other bad practices, not of native perversity, but by pure force of circumstances. And this is how fate (or an enterprising publisher) turned me from an innocent and impecunious naturalist into a devotee of the muse of shilling shockers.The author is being far too hard on himself. Philistia is no shilling shocker; it contains neither crime nor violence. One life is lost, but this is the result of an unfortunate accident. It's clear that Allen had no interest in writing an entertainment, rather he saw Philistia as an opportunity to employ fiction as a means of sharing his thoughts on science, evolution, religion, politics, and the distribution of wealth. If this sounds in any way dry, I assure you that it is not. Allen comes up with a clever story about hypocrisy, injustice, and privilege in Victorian society. Its characters are very much alive.

I really did want Herbert Le Breton to die.

As a first time novelist, Allen's greatest fault lies in his reliance on introspection... needless introspection... pages of needless introspection.

Pages.

Dear Mr. Chatto,Many thanks for your letter of hints about my unfinished novel. "Philistia" is certainly a very taking title, and I shall be very glad to adopt it. If you want to announce the novel in your programme for the "Gentleman's" (as I suppose you will), I think it had better be under that name.

As to not killing Ernest le Breton, I hardly see how one is to get out of it. To me, it seems almost the only possible end. If you feel very strongly that readers won't allow him to be killed, I will try to find some other alternative, but it will be difficult to manage. If one made him recover or get on well in the world, then there would be no dénouement, and, as a matter of character, I doubt whether such a person ever "would" get on well. However, I shall be guided by you in the matter; and if you think it indispensable that Ernest should live, I will try to work out another conclusion. I intended from the first that Ronald should marry Selah; and if Ernest doesn't die, there is no reason why Lady Hilda shouldn't marry Berkely.

Yours very faithfully,

Grant Allen.

As a result, I came away from Philistia feeling so very, very sad.

Bending over towards where Hilda sat, he took her hand in his dreamily: and Hilda let him take it without a movement. Then he looked deeply into her eyes, and felt a curious speechlessness coming over him, deep down in the ball of his throat.

I think we can all agree that it is the better title.

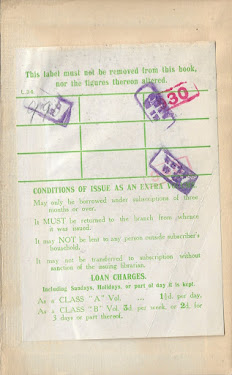

Object: "A NEW EDITION" published two years after the author's death, my copy was once part of Boots Booklovers Library. I'm not sure how to read this label, pasted to the rear endpaper.

Someone may be able to enlighten.

I purchased the book in 2018 from a British Columbia bookseller. Price: US$35.00.

Access: Philistia first appeared in 1884 numbers of The Gentleman's Magazine under the pseudonym "Cecil Power." Later that same year, it was published by Chatto & Windus in a three-volume edition.

The 1888 Chatto & Windus "cheap edition" can be read online here thanks to the Internet Archive and Emory University. The cover illustration is interesting in that it depicts a scene featuring Rupert and Selah, two minor characters:

As I write this, no copies of Philistia, in any edition, are being offered online.

Remarkably, Allen's 1883 letter to Andrew Chatto may be purchased as part of a small collection that also includes a copy of The Woman Who Did inscribed by the author to Andrew Lang.

My birthday is in August.