The Black Magician

R.T.M. Scott

New York: Triangle, 1938

244 pages

The Black Magician is the first Aurelius Smith novel, but it does not mark his debut. Earlier adventures appeared throughout the early 'twenties in the pages of

Adventure,

The Black Mask,

Action Stories, and other pulp magazines. Back then, Smith was an agent with the Criminal Intelligence Department of India. How he came to lose his position is covered in one of those adventures, though I can't say which one. Was it "The Emerald Coffin" (

Detective Tales, April/May 1923)?

Just a guess.

Whenever it happened, whatever the cause, the Aurelius Smith of

The Black Magician is no longer with the department. Now a private detective, he lives and works in a converted Manhattan garage with manservant and cook Langa Doonh, pretty stenographer Bernice Asterley, and a former Chicago street kid named Jimmie. Nothing is to be made of the living arrangements; Langa Doonh's space is by the kitchen, Bernice has two rooms to herself by the main door, and Aurelius and young Jimmie sleep on the second floor.

Again, make nothing of it.

Those unfamiliar with Aurelius Smith – Mr J.H. Scanton, for example – may be taken aback by his languid, seemingly indifferent demeanor. Scranton visits the former garage because he wants Smith to catch the man who stole his wife's necklace at the Hotel Magnifique:

"Necklace an investment?" queried Smith. "Will you suffer if you don't get it back?"

"Certainly not!" retorted Scranton. "I could lose ten times as much and sleep well. I'm here because I never let anybody beat me and the police have failed."

At that, Smith declines the case, and Langa Doonh ushers an astonished Scranton to the door. A second prospective client, a man named Grayson, will offer something more mysterious and less self-serving, but before he can begin, Jimmie bursts into the room: "Gee! Mr. Smith! Dere's a swell guy croaked on de front steps wid a stovepipe lid!"

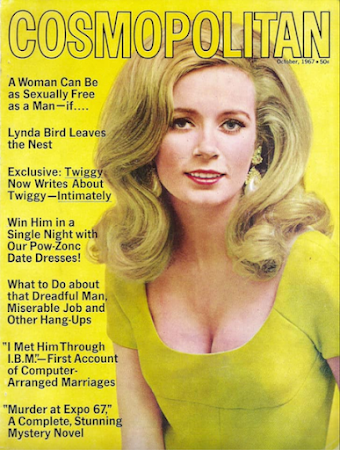

The dead man is, of course, Scranton, as depicted here with Smith on the cover of the July 1929 issue of

Compete Detective Novel Magazine:

Searching for a pulse, Smith notices a faint pin-prick on the dead man's right thumb. Resting beside the body is a small, five-pointed silver star.

After the police arrive, Smith returns to Grayson, who shares his concerns for the wellbeing of the female employees working in his department store. In the space of two short months, one has committed suicide and another has been placed in a sanatorium. Then, just yesterday, Grayson's secretary suffered a breakdown after opening an envelope to find a small, five-pointed silver star!

Young Jimmie is sent out to trail anyone who looks to be searching the ground where Scranton had fallen. The payoff is nearly immediate, leading Smith to Jerome Cardan, a mystic who claims to be the reincarnation of sixteenth-century Italian polymath

Girolamo Cardano. The charlatan – is he a charlatan? – has been using his skills as a mesmerist to manipulate Grayson's wife in order to get his hands on the family fortune.

But to what end?

When first identified as the villain, Cardan tells Smith that he wants a million dollars in order to "erect a suitable institute of knowledge in Europe." Later in the novel, the villain reveals that his goal is half of Grayson's wealth, which he will use to seize power in Russia. I didn't much care which was true; my interest had long wained as Smith came to rely less on deduction and more on derring-do.

What kept me reading to the end were trace elements of the author's life. For example, the detective makes several references to his involvement in the Great War, including a four-page account of an experience he'd had while serving with Canadian forces at Ypres. Scott himself fought at Ypres as a captain in the 21st Battalion. His exit from the war came in 1917 – the result of a shell concussion which left him with headaches and deafness in both ears.

(Interestingly, one of the mysteries of the novel is explained by Cardan's "supernormal hearing." He's able to trace Smith's movements about a room by focussing on the ticking of the detective's wristwatch.)

A regular contributor to

Mystic Magazine, Scott's interest in what is referred to as the "superphysical" is reflected not only in Cardan but in Smith. The characters' initial meeting takes place in a room lined with centuries-old copies of

Pistis Sophia, Iamblichus'

Theurgia, and the works of Cornelius Tacitus. Discussions of Paracelsus and Madame Blavatsky will figure, and Smith will challenge Grayson over the department store owner's atheism.

|

The November 1930 issue of Mystic Magazine,

featuring two articles by Scott:

'Mysteries of India’s Magic' and

'Mystic Magazine Gets Exclusive Message

from A. Conan Doyle.' |

The end couldn't come fast enough, yet I was left wondering whether Smith hadn't found employ with some other secret service. He's turned down Scranton's offer of $10,000 (the equivalent of $149,000 today), had spent money with abandon in chasing Cardan, and had taken no payment from Grayson. How was he able to support himself, never mind Bernice, Jimmie, and Langa Doonh?

Ah, but let's not focus on the material world.

Object: A cheap production consisting of scarlet cloth boards, yellowing paper stock, and a poorly printed dust jacket, my copy was purchased last year from a Toronto bookseller. Price: $10.00. The uncredited jacket illustration depicts an event that doesn't take place in the novel. Is that meant to be Bernice? Whoever it is, she looks cold.

Access: The Black Magician was first published in July 1925 by Dutton. As far as I've been able to determine, the months that followed saw a second Dutton printing and two more from A.L. Burt. A UK edition was published in 1926 by Heinemann. In July 1929,

The Black Magician reappeared as one of four works in the aforementioned issue of

Complete Detective Novel Magazine. Given that the issue is 144 pages in length, I think it safe to assume it is an abridged version. My 1938 Triangle edition marks its last appearance in the English language.

The novel has appeared in at least two translations:

Auf der Spur des schwarzen magiers (Munich: Georg Müller, 1928) and

Le magician noir (Paris: Librairie des Champs-Elysées, 1952).

Library and Archives Canada has a copy of the novel, as does the University of Alberta.

C'est tout. It appears no Canadian library has either translation.

Not many copies are listed for sake online. At the time of this writing, at US$8.99, the least expensive was a Burt in "acceptable condition," lacking dust jacket. A Dutton copy caps up things off at US$30.09 (VG+, lacking dust jacket). My advice is to buy the cheapest.

As always, print on demand vultures are to be ignored.