,

The Man from Krypton: The Gospel According to Superman

John Wesley White

Minneapolis: Bethany Fellowship, 1978

175 pages

John Wesley White died on September 4, 2016, the very same day Mother Teresa was canonized by Pope Francis; White being a Billy Graham Evangelistic Associate, I consider this a coincidence.

Rev Dr White was no stranger to the Dusty Bookcase, yet his passing was not noted here. The Dusty Bookcase has to do with the forgotten, the neglected, and the suppressed. In the days following his death, John Wesley White was remembered as never before.

Looking through his obituaries, I find it curious that few mention the preacher's written work. The Toronto Star obit informs that White wrote "over twenty books," singling out Re-entry (which I've read) and The Prodigal Son (which does not exist). My introduction to White, the man, and his prophesies didn't come through Agape (his TV show) or 100 Huntley Street (not his TV show), rather Arming for Armageddon, which I found fourteen years ago in the Stratford, Ontario Salvation Army Thrift Store.

|

| John Wesley White on 100 Huntley Street, January 1988. |

Arming for Armageddon espouses an all too common, all too unappealing brand of born again Christianity, but White's writing, particular and peculiar, had me yearning for more. Over the next few years, that same Thrift Store yielded a second White title, Thinking the Unthinkable, and a third, the aforementioned Re-entry, but then my family moved eastward. Since then, I've had to rely on online booksellers, The Man from Krypton being my most recent. I'd long wanted this book because of something I'd read in my first White book.

In Arming for Armageddon, Rev Dr White condemns Christopher Reeve's Superman for "preparing the human psyche for an Antichrist."

The Man from Krypton isn't quite so damning. Published to coincide with the release of

Superman: The Movie, its first chapter cribs liberally from issues of

Time. This quote from creative consultant Tom Mankiewicz sets the tone: "Whatever Jimmy Carter is asking us to be, Superman is already. What we are really giving people is the Christian message: that we should all be honest, love each other and be for the underdog."

Being familiar with White's writing, I questioned the veracity of the Mankiewicz quote, only to find it in the August 1, 1977 edition. Further surprises followed: Rev Dr White praises Jimmy Carter, happily notes increasing church attendance, and remarks on young people's attraction to things spiritual, as reflected in the popularity of Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Hallelujah!

So positive, so uplifting, the first chapter of The Man from Krypton is unlike anything found in the Rev Dr's other books. The remaining nine chapters are classic White: disinformation ("Murder in Canada has doubled in a dacade [sic]") and misinformation ("There are some current movies entitled Fantom From Space and Tony and Tia, Two Cosmic Beings — From Outer Space."), accompanied by the usual muddled rambling:

"Sorry seems to be the hardest word," sings Elton John. Eric Segal, the Yale professor who became famous as the author of Love Story, defines love as never having to say you're sorry. Coming to Christ, as Billy Graham has demonstrated in his prayer with millions of repenting sinners, must begin with: "I am sorry for my sins," or words to that effect.

According to White, Carrie is the sequel to The Omen and Shakespeare wrote The Little Prince. An Oxford graduate, he attributes these words to the Bard:

Le petit prédicateur writes of men named Timothy O'Leary, Gue Grevara, Freddie Printz, and Terry Keith. On his planet, Hollywood produces "Satan thrillers" titled Satan's Men, The Devil's Widow, Mistress of the Devil (starring Liv Ullman), and The Devil's Mistress (starring Andy Warhol), none of which are recognized by IMDb.

Preacher White was always quick to judge; anything might be condemned as a Satan thriller. Consider Shout at the Devil, the 1976 action-adventure inspired by the 1905 sinking of SMS Königsberg. White is wrong in describing it as a Satan thriller, just as he's wrong that it stars "Marvin Moore."

After all these years, after all his books, I feel I've come to understand White's confusion. Until 1996, the year he was pretty much silenced by a stroke, the Rev Dr was extremely busy, flying around the world, spreading his interpretation of the Bible. I believe his habit of referencing billboards and newspaper headlines is a reflection of the fast-paced, jet-setting evangelical lifestyle. The preacher had little time for contemplation, never mind investigation. Writing of Tony and Tia, Two Cosmic Beings — From Outer Space, White is almost certainly referencing Disney's 1975 Escape to Witch Mountain, a film he almost certainly never saw.

As a White scholar, there was no challenge in linking Tony and Tia, Two Cosmic Beings — From Outer Space and Escape to Witch Mountain, but I am stumped by his description of a non-existent Blood, Sweat and Tears album. What inspired this?

The rock group "Blood, Sweat and Tears" combined Mick Jagger's "Sympathy for the Devil" and Moussorgsky's "Night on Bald Mountain" in an album entitled "Sympathy to the Devil — Symphony for the Devil." Tragically and quickly Eve's sympathy for the devil had turned the human race into rendering a "symphony to the devil" which is playing and slaying at a higher decibel level today than the devil has directed in the long history of man.

One might ask what any of this has to do with Superman.

The answer is not much.

The Man of Steel is the focus of the first five pages – "Joe Schuster," "George Reeves," and "Lennone Lemmon" figure – after which he is relegated to the introductory paragraph of each chapter; these being typical:

In the film, Superman has X-ray eyes that can see through virtually anything. He knows everything about anybody with whom he has to so. This, of course points us back to Jesus Christ.

Superbaby grows into Superman and seems to be able to do anything. He can leap over skyscrapers in one gargantuan bound. He tames bursting floodwaters from a collapsing dam. He catches a crashing helicopter in midair. The people are left asking: "Is there anything too hard for Superman?" Which of course takes us straight to the Bible.

There is one brief mention of Superman outside these introductory paragraphs, but it comes with a degree of resentment:

Jesus could walk over hills or mountains at will, calm stormy waters, and save a sinking ship in mid-sea. Superman's feats of leaping over a skyscraper, calming a bursting dam, and catching a crashing helicopter were topped by Jesus years ago!

White knew little about Superman other than what he'd read in Time. The Gospel According to Superman was nothing more than a subtitle used to sell books.

John Wesley White's world isn't Earth One or Earth Two. Bizarro World comes closest; ugly, disturbing, nonsensical, and usually good for a laugh.

Favourite short passage:

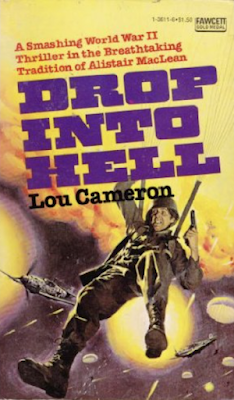

There's a book title Drop Into Hell. Christians are to urge people not to drop into hell.

Favourite short passage (runner-up):

"If I were God, this world of sin and suffering world break my heart!" Goethe, the German, reckoned. Mr. Goethe, that's precisely what it did when Jesus hung on the center cross!

Favourite feature length passage:

Saved! That word conjures up a lot of impressions in our minds. A hockey goalie makes about thirty saves per game. A baseball relief pitcher might manage twenty or so saves in a season. A crop is saved by good rain. A surgeon saves a patient's life by the educated skill of his hand on the scalpel. A policeman saves a child from drowning. Churchill saved England from Hitler. Erica Jong writes her best seller, How to Save Your Own Life, which the way it defies morality and defies immortality, might better be entitled How to Ruin Your Own Life. Whole pages in magazines and papers are sold to bank advertisements which invite: "SAVINGS –That's What It Is All About." "SAVE NOW – During our Annual Sale" publicizes every store worth its salt, sooner or later. A headliner during the Rumanian earthquake disaster reads: "Buried for 62 Hours, Waitress Saved in Bucharest." Yet when the word is used spiritually, it is nearly unknown.

Object and Access: An unexceptional mass market paperback. The cover illustrator, who seems to be channelling 1966 Batman, is not credited.

Eighteen copies are listed for sale online, the least expensive priced at US$5.23. One Maryland bookseller offers a signed copy at US$5.29. I'd say it's worth the additional six cents.

Related posts: