Grant Allen

New York: Harper & Brothers, 1891

271 pages

Reviewing Gilbert Parker's The Right of Way a while back, I expressed my opposition to the idea of starting a novel with dialogue. "'Not guilty, your Honor!'" – italics and all – is its first line.

The first line in The Great Taboo is "'Man overboard!'"

Better than "Splash!" I suppose.

The man who has gone overboard is, in fact, a woman. No one knows this better than English civil servant Felix Thurston. An instant earlier he'd grasped Miss Muriel Ellis' slender waist as a wall of water struck the deck of the Austalasian:

The wave had knocked him down, and dashed him against the bulwark on the leeward side. As he picked himself up, wet, bruised, and shaken, he looked about for Muriel. A terrible dread seized upon his soul at once. Impossible! Impossible! she couldn't have been washed overboard!

Thurston dives into the "fierce black water" – I should've mentioned it is nighttime – intent on rescue. Lifebelts are flung in their general direction and a boat is lowered, its light playing upon the waves, but to no avail. After an exhaustive search, the crewmen return to the ship. Their captain is philosophical:

"I knew there wasn't a chance; but in common humanity one was bound to make some show of trying to save 'em. He was a brave fellow to go after her, though it was no good, of course. He couldn't even find her, at night, and with such a sea as that running."In fact, Mr Thurston did find Miss Owen; Felix and Muriel cling to each other even as the captain speaks. Buoyed by lifebelts, the pair drifts toward a reef that bounds Boupari, "one of those rare remote islets where the very rumor of our European civilization has hardly yet penetrated." As the new day dawns, Felix begins to make out signs of habitation. He's well aware that the Polynesian islands are home to "the fiercest and most bloodthirsty cannibals known to travellers." And so, he is on his guard as smiling, friendly souls paddle to transport the two castaways from reef to islet.

Felix and Muriel are not eaten, rather they're made the King of Rain and Queen of Clouds. The two are considered gods, subservient only to the high god Tu-Kila-Kila. They are also deemed "Korong," a word the civil servant, who is otherwise conversant in Polynesian languages, knows not.

Grant Allen was all too dismissive of his novels, but I'm not. The best part of worthwhile nineteenth-century Canadian fiction was written by Allen. That said, I have been dismissive of his adventure novels, Wednesday the Tenth (aka The Cruise of the Albatross) included. Published the same year The Great Taboo, it too features cannibals.*

I haven't had time to read those books, but have read Mary Beard's review of Robert Fraser's 1990 The Making of ‘The Golden Bough’: The Origin and Growth of an Argument (London Review of Books, 26 June 1990), in which she writes that The Great Taboo "turned Frazer’s metaphorical journey into a literal tale of travel and adventure." It is, in her words, "a crude and simplified retelling of The Golden Bough," and "important for our understanding of the immediate popular reception of Frazer’s work."

The last sentence is much better than the first.

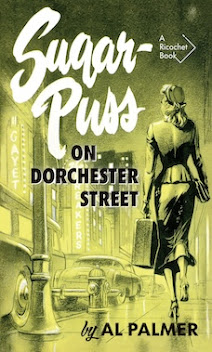

* Five years ago, I posted a Grant Allen top ten in which The Cruise of the Albatross takes the final spot. At the time, I'd read all of twelve Allen novels. I've now read eighteen. The Cruise of the Albatross has fallen to fourteenth position.Trivia: Being of a certain age, I couldn't read the title without thinking of the Great Gazoo. The name Felix Thurston reminded me of this more famous fictional castaway:

Object and Access: My first American edition was purchased four or five years ago. I cannot remember how much I paid, but it couldn't have been fifty dollars. The true first is the British first. Published in 1890 by Chatto & Windus, I see evidence of a second printing the following year.

No copies of either is listed for sale online today. It would appear that there have been no other editions.

The Harper & Bros edition can be read online here courtesy of the Internet Archive.