The Leader-Post, 7 January 1938

The Ottawa Citizen, 7 January 1938

A JOURNEY THROUGH CANADA'S FORGOTTEN, NEGLECTED AND SUPPRESSED WRITING

Like the Vatican in the old days, Canada has an index of forbidden material. Ours is a filing cabinet of index cards, kept by Customs and Excise officials on the sixth floor of the Connaught Building just around the corner from the Château Laurier. The keeper of the index, in effect the chief of Censorship Canada, is Lt.-Col. John Merner, a sixty-two-year-old retired army officer who bears the official title Head, Prohibited Importation Section. Along with a departmental lawyer and a couple of clerks, Merner protects Canada from books, films, videotapes, and other materials that he believes (as Section 99201-1 of Schedule C of the Canada Customs Tariff puts it) "treasonable or seditious or of an immoral or indecent character."...If a customs decision goes against you, you can appeal. But you may find yourself catalogued among the 100,000 names contained in the Customs Intelligence File. If your appeal fails, the government can destroy the material and you lose your court costs. If your appeal succeeds, the government returns the material to you – and you lose your court costs anyway. Not many people appeal....When I visited the office recently, the Head, Prohibited Importation Section, and his helpers were busily keeping Canada free of material that might subvert the civil order or endanger morals. They were doing so in something close to secrecy, protected by a bureaucratic wall that can be penetrated neither by parliament nor by the press, or even by the minister of revenue himself. Other censors – such as the Ontario film censors – find themselves regularly embroiled in headline-making conflicts, but all is quiet in the Connaught Building. So far as an outsider can determine, there are not even internal struggles over what to censor. Only once in ten years, Merner recalls, has the minister of revenue – it was Robert Stanbury – actually fought one of his decisions. And, says Merner, "He lost."

These same sorry sods would find fit in This was Joanna, which was published twelve months earlier. We never actually meet Joanna – she's found dead on page one by an unnamed fisherman, as depicted on the cover of the publisher's American edition: "...for one witless moment he looked down on the haunting perfection that was Joanna, the closed eyes in a kind of rapture, the long, strained throat, twisted torso, magnificent breasts, profound hips, proud legs, crouched in death like a supple cat."

These same sorry sods would find fit in This was Joanna, which was published twelve months earlier. We never actually meet Joanna – she's found dead on page one by an unnamed fisherman, as depicted on the cover of the publisher's American edition: "...for one witless moment he looked down on the haunting perfection that was Joanna, the closed eyes in a kind of rapture, the long, strained throat, twisted torso, magnificent breasts, profound hips, proud legs, crouched in death like a supple cat."At last she stood nude before me. When I looked at her I was shocked to see the most brazen smile on her face.

Then, without hesitation, her fingers sure, carefully, slowly, she began to undress me. I went slightly hysterical then. I began to shudder to laugh, to giggle, to squirm. I simply went berserk. In the grip of nameless emotions that shook my whole body and dazed my mind I began to fight with her, to hit her, to drag her toward the bed.What Joanna thought of this I don't know. We have never discussed it. I only know that later, all passion spent, as I lay beside her in the muttering gloom, I realized that on our wedding night I had gone mad, had beaten my wife and had virtually raped her.

Joanna never forgives Charles, whose desperate attempts to win her back render him a cuckold. The tryst with the newspaperman is just the first in a series of extramarital flings. It's with penultimate lover Ted Wrisley that Joanna's amorous adventures come to a climax. A sensualist who owes much to J.-K. Huysmans' Jean Des Esseintes, Wrisley introduces Joanna to "the arts of which immortal Ovid and the Marquis de Sade have written." He takes delight in showing his "chamber of horrors" to the newspaperman:

Joanna never forgives Charles, whose desperate attempts to win her back render him a cuckold. The tryst with the newspaperman is just the first in a series of extramarital flings. It's with penultimate lover Ted Wrisley that Joanna's amorous adventures come to a climax. A sensualist who owes much to J.-K. Huysmans' Jean Des Esseintes, Wrisley introduces Joanna to "the arts of which immortal Ovid and the Marquis de Sade have written." He takes delight in showing his "chamber of horrors" to the newspaperman:On the walls of the room were hung all sorts of gadgets of torture; long needles, small, hairy whips, knouts, knives sharp as razors, silken threads of unbelievable length. Over the mantlepiece were afixed two large peacock feathers; the end of one was a rubber stopper, the end of the other a handgrip. I dared not ask the significance of these feathers for fear of being told.Suspended from the ceiling were two long cords, obviously used to hold a person up from the floor by his (or her) thumbs. On the floor, as if alive, lay the stuffed corpse of a sinuous cobra. The most unspeakably evil paintings adorned the walls and, in one corner of the room under a blue light, sat the grinning statue of Priapus, the phallic symbol of the ages.

Object: A mass market paperback that is typical of News Stand Library's shoddy production values. Streaks of black ink run along the edges of a dozen or so pages, making for challenging reading. The author's name is misspelled on the cover and title page (but is correct on the spine and back cover). "I before E, except after C", I suppose.

Object: A mass market paperback that is typical of News Stand Library's shoddy production values. Streaks of black ink run along the edges of a dozen or so pages, making for challenging reading. The author's name is misspelled on the cover and title page (but is correct on the spine and back cover). "I before E, except after C", I suppose.

What titles did they target? To Have and Have Not was one; John O'Hara's Ten North Frederick was another. Works by William Faulkner, John Dos Passos and George Orwell were also deemed indecent. Which ones? Who knows – the League clutched the list to its collective bosom, making certain that the titles remained secret.

What titles did they target? To Have and Have Not was one; John O'Hara's Ten North Frederick was another. Works by William Faulkner, John Dos Passos and George Orwell were also deemed indecent. Which ones? Who knows – the League clutched the list to its collective bosom, making certain that the titles remained secret.

The Dusty Bookcase:A Journey Through Canada'sForgotten, Neglected, and Suppressed Writing

The freedom to write books, and thus to disseminate ideas, opinions and concepts of the imagination – the freedom to treat with complete candor an aspect of human life and the activities, aspirations and failings of human beings – these are fundamental to progress in a free society.

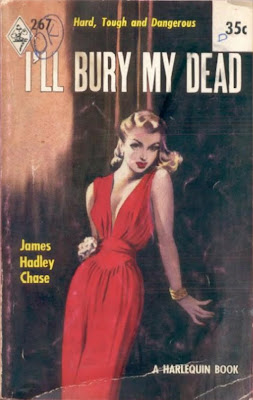

From the cover you might think the story was about... er, well, rolling in the hay. But that couldn't be further from the truth. Let's just say that the plot involves jealousy, hatred, physical abuse, rape, suicide, murder, racism, adultery, a couple of unwanted pregnancies and a mother so unlikeable that you are actually glad when she’s stabbed by her son. In any case, that one was nixed.

Ms Zinberg: "Also, grammar and spelling standards have changed quite a bit in sixty years."Ms Macintosh: "Grammar and spelling has [sic] also changed quite a bit in the past sixty years..."

"What's a loogan?""A guy with a gun.""Are you a loogan?""Sure," I laughed. "But strictly speaking a loogan is a guy on the wrong side of the fence."

Remember, our intention was to publish the stories in their original form. But once we immersed ourselves in the text, our eyes grew wide. Our jaws dropped. Social behavior — such as hitting a woman — that would be considered totally unacceptable now was quite common sixty years ago. Scenes of near rape would not sit well with a contemporary audience, we were quite convinced. We therefore decided to make small adjustments to the text, only in cases where we felt scenes or phrases would be offensive to a 2009 readership. Also, grammar and spelling standards have changed quite a bit in sixty years.

Everyone in house has taken such interest and pride in this project, and we're delighted that the collection is now out in the marketplace. We hope they will also accomplish what the cover art exhibition attempted to do: "offer a unique insight into the profound changes that have occurred in women’s lives over the past six decades — from shifts in private desires to shifts in the politics of gender"!