The Darling Illusion

Margerie Scott

London: Peter Davies, 1954

246 pages

Olivia Thompson's dead body lies in a slowly growing pool of blood, an apron belonging to her housekeeper, Mrs Baker, covering the head. Looking down, Inspector of Detectives John Sims believes the death a suicide, but Doctor Jordan Plant, the coroner, suggests otherwise: "I've been thinking—John, have you ever known a woman to shoot herself in the face?"

Olivia's final days favour the doctor's opinion. A young actress who had spent much of the Second World War in London, she'd returned to her Canadian hometown only four days earlier. In the short time between arrival and death, Olivia had purchased and moved into her childhood home. She'd hired Mrs Baker, ordered new furniture, and had started in on plans to renovate. No, nothing speaks to suicide, which made this reader question the inspector's rush to judgement. I didn't know what to think of the coroner, who has this to say about the murderer: "It's more likely to be a woman than a man to do a thing like that to another woman."

Is it? I honestly have no idea.

Save the housekeeper, Olivia had no contact with anyone except Louise Brand, Edith Temple, and Mary Anne Nesbit, each of whom had visited in the days leading to her death. Names from Olivia's past, they all have reasons to hate her. The novel's structure, coupled with Dr Plant's conviction, encourages the expectation that one of these women did the bloody deed. But which one?

Don't look to Doctor Jordan Plant or Inspector John Sims for the answer, they feature only in the first of the novel's five sections. "Louise," the second section, serves to introduce a living Olivia and her family. Mother Meg, was a music hall performer in the Old Country. Father Tom was a smitten medical student, disowned over his choice of mate. Together Meg and Tom emigrated to a small Canadian city (read: Windsor), where they raised their children, Olivia and Gerry, and earned a reputation as a couple of carefree oddballs.

But what of Louise? Though this is her section, she features hardly at all. It's instead given over to Reg Barnes. The son of a rumrunner who made a fortune during American prohibition, he's expected to marry pretty, buxom blonde Louise Williams, a member of a prominent family that had achieved its riches in the very same manner. The Barneses and Williamses have money and pretense, but Reg is attracted to Meg and Tom's way of life... and their daughter. On the eve of the announcement of his engagement to Louise – invitations are back from the printer – he asks Olivia to marry him. She declines, Reg marries Louise, and in the section's climax, calls out Olivia's name on his wedding night.

"Edith," the novel's second section is named for Edith Temple. A frigid widow with a fetish for cleanliness, she'd once married a younger man, and had endured sex until pregnant. Her unfortunate husband was mercifully shot to death whilst running rum to thirsty Americans. Edith gave birth to a son, Jack, whom she raised with her cold, cold heart. It's no wonder that he's drawn to Meg and Tom's warm, loving home. Like Reg, he develops a thing for Olivia. Things take a turn when Jack learns of Olivia's plans to study theatre in London. He pleads with her to stay, is met with derision, and kills himself.

Though only sixty pages in length, "Mary Anne" may be worthy of a paper. Historians will find interest in its portrait of a family, Meg and Tom's, in wartime London, but the real value comes in its depiction of homosexuality and attitudes towards same. We begin in Canada. Mary Anne Nesbit and younger brother Bill are orphaned in their early teens. Against all odds, with the use of an otherwise useless aunt, they manage to maintain their independence. When comes the war, Bill is sent to fight overseas. Mary Anne joins the Canadian Red Cross so as to be closer to her brother. On leave, Bill visits Meg and Tom, now living in London, and surprises everyone by proposing to Olivia. She accepts, only to frustrate her betrothed by deferring the wedding for the stage. Bill goes on a bender, ending up in a King's Road pub. A man named Christopher Bentley sidles up to him at the bar and, when Bill gets too drunk to stand, takes him back to his flat. From this point on, despite initial "self disgust" on Bill's part, he and Christopher become a couple.

Mary Anne cannot accept her bother's new relationship, as evidenced in this exchange:

"It's your fault, " Mary Anne jumped up and stood facing Olivia, her face working, her hands balled into fists. "I didn't want him to marry you because I knew you'd never make him happy; I know as much about you as you know about me, and I know you'e selfish and cruel and always have been, but you did get engaged to Bill and you should have kept your promise instead of making him so miserable that he went off and got drunk and took up with... this..." she paused, thinking, and Olivia said with deadly sweetness:

"Is 'pansy' the word you're looking for?"

Citing this passage out of context is deceiving; Olivia can be mean, but here she's defending Bill. His relationship with Christopher is not only accepted, but embraced by Meg, Tom, Olivia, their upstairs neighbour... really, everyone except his sister.

Olivia's defence of Bill is made more interesting in that it is so uncharacteristic. She's depicted as a dislikable, selfish, self-centred, uncaring woman whose only desire is stardom on the stage. In this she's supported by her parents. Meg and Ted's return to England has nearly everything to do with helping Olivia to achieve her dreams, though they'd be quick to point out that it also has something to do with the overseas wartime service of their son Gerry.

Remember Gerry?

The male characters in

The Darling Illusion serve no purpose other than to propel the plot. Ted is nothing more than the most adoring of husbands, happily supporting his wife's whims, including her sudden decision to return to England. Gerry, at best the ghost of a character, provides additional reason for Meg and Tom's relocation. Once his parents are reestablished in London, he is – quite literally – killed off. Reg, Jack, and Bill exist only to provide Louise, Edith, and Mary Anne with reasons to hate Olivia.

It wasn't until I'd finished the novel that I read this in the jacket copy: "

The Darling Illusion is not a thriller or detective story, but a penetrating novel of character."

A bold claim, it is both true and false.

It's true that

The Darling Illusion is not a thriller or detective story; Inspector of Detectives John Sims and coroner Jordan Plant are nowhere to be found after the eighth page. It is not true that

The Darling Illusion is a penetrating novel of character. Of its population, only Meg, Edith, and Mary Anne live. This is an unusual novel in that its protagonist, Olivia, exists as little more than a sketch; she's not nearly so realized as the secondary female characters. In this lies the novel's great flaw. Reg, Jack, and Bill all fall in love with Olivia, but the reader will be hard pressed to understand.

Midway through the novel, the omniscient narrator shares this about Bill's feelings for Olivia: "He loved her, but didn't like her."

I've never quite understood how that works.

I didn't love her, I didn't like her, and I didn't hate her; she never seemed real. It's no wonder then that Louise, Edith, and Mary Anne didn't kill Olivia.

I spoil little in revealing that her death can be blamed on a mouse.

I'll leave the rest to your imagination.

Epigraph:

The lines come from Roberts' "The Tantramar Revisited," first published in 1883.

Query: In the years after the war, would Olivia have been able to fly into Canada with a loaded revolver?

The novel's final page hinges on the answer.

About the author:

In fact,

The Darling Illusion was the author's third novel, following

Life Begins for Father (London: Hutchinson, 1939) and

Mine Own Content (1952).

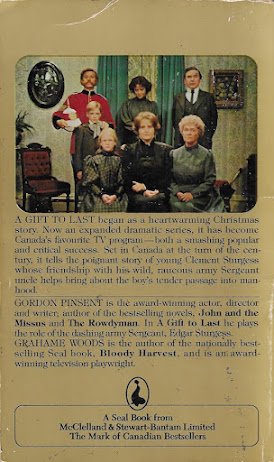

Object: A slim hardcover featuring mustard-coloured boards. The jacket illustration is uncredited. I think the artist captured something of Olivia, a woman whom Dr Plant describes as a woman who "could give the impression of beauty."

My copy was purchased for nine American dollars from an Australian bookseller in mid-March. It arrived two weeks ago. As you might imagine, I'd pretty much given up.

It features this book trade label:

Access: Davies'

The Darling Illusion enjoyed only one printing. There was a McClelland & Stewart edition, but I've never seen it. Copies of the novel can be found at Library and Archives Canada, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, and nine of our university libraries. Serving the city in which the author lived, the Windsor Public Library holds none of Scott's novels, though it does have

Beyond All Recompense: The Story of the Honourable Profession of Nursing in Windsor (1954), a booklet she wrote for the Windsor Centennial Festival.

Three copies of

The Darling Illusion are currently listed for sale online, the least expensive – ten Australian dollars – being in "Good+" condition. Were I to revisit my March purchase, I'd be tempted by the American bookseller offering

The Darling Illusion (M&S edition) and her subsequent novel,

Return to Today (Peter Davies edition), for forty-four American dollars.

My thanks to Scott of Furrowed Middlebrow for bringing Margerie Scott to my attention. His writing on the author can be found in this post.

Related post: