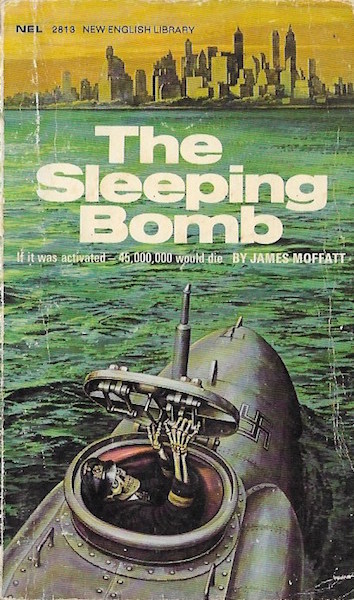

The Sleeping Bomb

James Moffatt

London: New English Library, 1970

James Moffatt

London: New English Library, 1970

125 pages

Jim used to say, "It's a business, it's the way I make my money, and I can live this way. I mean, people who write hardbacks can take a very, very long time to write them, which is very nice if you've got a good income behind you. Jim didn't have. I mean, he simply wrote to live, and he enjoyed doing it.— Derry Moffatt, 1996

The Sleeping Bomb appeared at news agents a few months after the author's pseudonymously published Skinhead. I wonder whether Moffatt knew by that time that he'd scored a smash hit. Skinhead was easily his biggest seller, spawning Suedehead (1971), Boot Boys (1972) Skinhead Escapes (1972) Skinhead Girls (1972), Top Gear Skin (1973) Trouble for Skinhead (1973) Skinhead Farewell (1974), and Dragon Skins (1975).

The Sleeping Bomb is a lesser work. Bereft of braces and Doc Martins, it begins on the other side of the pond – beneath the Hudson River, to be exact – with the discovery of a thirty-year-old one-man Nazi submarine during the construction of a new tunnel linking New York and New Jersey.

CIA agent Paul Henderson is assigned the case.

Why the CIA?

I have a theory – which is mine – that Moffatt knew he was out of his element when it came to responsibilities, jurisdictions, command structures, and the like. For this reason, he sets the novel in not-so-distant 1975, a year in which the armed forces of Canada, the United States, Mexican, and the United Kingdom fall under the centralized authority of the North Atlantic Defence Alliance. Intelligence agencies are being unified in a similar manner, which explains how Henderson ends up working under a Brit named Silas Manners

Why the CIA?

I have a theory – which is mine – that Moffatt knew he was out of his element when it came to responsibilities, jurisdictions, command structures, and the like. For this reason, he sets the novel in not-so-distant 1975, a year in which the armed forces of Canada, the United States, Mexican, and the United Kingdom fall under the centralized authority of the North Atlantic Defence Alliance. Intelligence agencies are being unified in a similar manner, which explains how Henderson ends up working under a Brit named Silas Manners

Not Silas Marner.

Not Miss Manners.

Because the sub is armed and booby-trapped, its hull cannot be breached. Dials, some broken, indicate that it contains a time bomb that is set to explode at some point in 1975. Whether government, intelligence or military, no one knows just just what will happen, but everyone is sure it'll be really, really bad.

Because the sub is armed and booby-trapped, its hull cannot be breached. Dials, some broken, indicate that it contains a time bomb that is set to explode at some point in 1975. Whether government, intelligence or military, no one knows just just what will happen, but everyone is sure it'll be really, really bad.

The situation is so dire that I wondered why Henderson and Manner were left on their own to figure it all out. Restructuring, perhaps. As in any Richard Rohmer novel, the pair spend a good amount of time flying from place to place in an effort to get to the bottom of things. In their travels, they learn that the sub carries a "parasitic bomb" which will kill everyone within an area amounting to 250,000 square kilometres.

The Americans published The Sleeping Bomb as The Cambri Plot. I mention this because because Cambri – "Project Cambri" – is referenced a couple of times early in the novel.

The Americans published The Sleeping Bomb as The Cambri Plot. I mention this because because Cambri – "Project Cambri" – is referenced a couple of times early in the novel.Sure seems important. The ABC Movie of the Week President of the United States has a conniption when Paul Henderson let's slip that he's heard about it:

"WHAT!! Where did you hear that name, Henderson?"Paul wished to hell he'd kept his big mouth shut. "In General Herschfeld's office, sir. I overheard it when I paid a visit to him...""Have you mentioned this to your colleagues?""No, sir!""Thank God!" The president's heavy breathing could be heard clearly.

Project Cambri involves rockets that can land on a pinprick. Their purpose is to carry documents and diplomats that might otherwise be intercepted by the Soviets.

That Project Cambri – note: not "The Cambri Plot" – is barely mentioned must have seemed strange to American readers. It vanishes in the early pages, only to reappear as the climax approaches. With three pages to go, I was interrupted by Kiefer, our nine-month-old Schnauzer. We played, and then went for a long walk.

As we made our way along our lonely rural road, I thought of everything that was wrong with the novel. I wondered whether visitors to East Germany were never searched. I tried to imagine Henderson piloting a locomotive across several hundred meters of railway ties, and then managing to get it back in the tracks.

Yeah, that happens.

Yeah, that happens.

More incredible was the Nazi plan, which involves planting a time bomb during the dying days of the Second World War and then waiting, waiting, waiting... The detonation, thirty years later, is intended to both bring about the reunification of a country that hadn't yet been divided and bring the world to its knees. Why not just set the bomb off in 1945? Why not kill millions and threaten millions more? Wouldn't that have brought the war to a sudden end? Wouldn't that have given Hitler the upper hand?

I'll never understand Nazis; James Moffatt's Nazis included.

Favourite passage: "CRAAAAASH! Wood splintered, flew in every direction. CRUUUUMP!"

Trivia I: New English Library's cover copy (below) was clearly written by someone who had not read the novel. The bomb would cover 250,000 square miles, not one thousand.

No neo-Nazis figure.

No neo-Nazis figure.

Trivia II: Silas Manners reappears in Moffatt's Justice for a Dead Spy (London: New English Library, 1971).

Object: A slim, cheap mass market paperback. The novel itself is followed by three pages of adverts for other New English Library books.

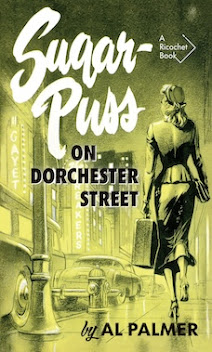

Isn't this tempting!

Access: The Sleeping Bomb enjoyed one lone printing. Five copies are listed for sale online at prices ranging from £3.95 to £6.19. Condition isn't much of a factor.

The Cambri Plot was published in 1973 by Belmont Tower. Copies of that edition range from US$4.10 to US$55.42.

The novel last appeared as a Spanish translation, La Vengganza de Hitler, "una novela escalofriante," published in Mexico City in 1974 by Novaro.

Whether academic or public, not one copy of any is held by a Canadian library.