Le Nom dans le bronze

Michelle Le Normand [pseud. Marie-Antoninette Desrosiers]

Montreal: Éditions de Devoir, 1933

Well, didn't this turn out to be a timely read.

A short novel,

Le nom dans le Bronze seems at first a light and pleasant love story. Our heroine, Marguerite Couillard, is the youngest daughter of a bourgeois family in the Quebec town of Sorel. Steven Bayle, the object of her affection, doesn't quite qualify as our hero, but he's not a villain either. Frankly, he's a pretty swell guy and a bit of a catch; even for Marguerite. Though an anglophone, Steven appears entirely at home in French Canadian society; were it not for his pesky Protestant faith one might even consider him assimilated. However, as their love grows, storm clouds gather in the

ciel lourd that opens the novel. Family and community shudder at the possibility of a

"marriage mixte", pressing upon Marguerite

"la différence de sang et la disparité de religion".

An intervention disguised as an invitation to visit friends in Quebec City brings an abrupt change in genre. What began as a romance novel becomes a Micheline guide, with Marguerite taking in the sights as friend Philippe fills her in on the history of the city, the province and her own family.

"Il y avait à Québec deux générations de Couillard, quand on construisit cette chapelle", he says before the church of Notre-Dame-des-Victoires, so named after the respective defeats of Englishmen

William Phips and

Hovenden Walker.

"Mais en 1759, l'ère des Victoires était passée et la chapelle fut incendiée par les bombes de Wolfe. Ce sont encore les mêmes murs, toutefois..."

The pressure put on Marguerite is relentless and none too subtle.

"Rien n'est plus affaiblissant pour notre peuple que ces marriages mixtes", she's told by her father.

"Justement ce matin, je m'irritais de constater combien des nôtres, pendant la guerre, ont épousé des Anglaises d'outre-mer..."

The

coup de grâce comes when Marguerite is taken to see the statue of

Louis Hébert, and its plaque bearing the names of Quebec's earliest settlers. She not only learns that she is a decedent, but sees that she bears the same name – Marguerite Couillard – as one of her ancestors.

Le nom dans le bronze. Says Philippe,

"Marguerite, épousez un homme au nom aussi respectable, et appelez votre premier fils: Couillard..."

And Bayle? Really, how respectable is that?

Their love is doomed. Sacrifices must be made for one's

"race".

Le Nom dans le bronze is a work from a different time. Times change, but we see remnants in the chronic xenophobia that plagues Pauline Marois' efforts to become the next premier of Quebec. Surrounded, as she is, by her base, she cannot see that her words alienate more than just those she considers

les autres. And so, we have an election in which a scandal-ridden, disgraced and very tired Liberal government is still in contention.

What Ms Marois fails to recognize is that her brand of bigoted, frightened nationalism began dying decades ago, and that a much younger, more confident generation – what Chantal Hébert astutely refers to as "the Arcade Fire generation" – want nothing to do with her kind.

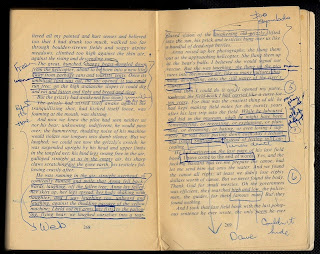

Trivia: The name "Marguerite Couillard" really does feature on the plaque in question (though, sadly, it can't be made out in this image).

Object: Rather bland paper wraps cover what is an otherwise attractive book. My first edition copy was bought last year from a bookseller in the village of St-Malachie, some 50 kilometres south-east of Quebec City.

Access: Though reprinted no less than three times in the 'fifties,

Le Nom dans le bronze is surprisingly hard to come by. Four copies are currently listed for sale online, only one of which is a first edition. Leather-bound, signed, inscribed and dated, this is the one to buy – a bargain at US$97.75.