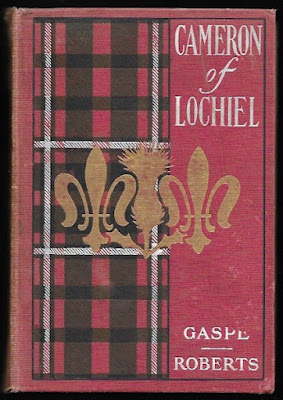

Cameron of Lochiel [Les Anciens Canadiens]

Phillipe[-Joseph] Aubert de Gaspé [trans Charles G.D.

Roberts]

Boston: L.C.Page, 1905

287 pages

Pulled from the bookcase on la Fête de la Saint-Jean-Baptiste, returned on Canada Day, I first read this translation of Les Anciens Canadiens in my teens. It served as my introduction to this country's French-language literature. Revisiting the novel four decades later, I was surprised at how much I remembered.

Les Anciens Canadiens centres on Archibald Cameron and friend Jules d'Haberville. The two meet as students at Quebec City's Collège des Jésuites. Cameron, "commonly known as Archie of Lochiel," is the orphaned son of a father who made the mistake of throwing his lot behind Bonnie Prince Charlie. Jules is the son of the seigneur d'Haberville, whose lands lie at Saint-Jean-Port-Joli, on the south shore of the Saint Lawrence, some eighty kilometres north-east of Quebec City.

Montreal's Lakeshore School Board – now the Lester B. Pearson School Board – was very keen that we study the seigneurial system.

And we did!

We coloured maps using Laurentian pencils; popsicle sticks and papier-mâché landscapes were also involved. There was much focus on architecture and geography, but not so much on tradition and culture.

We were not assigned

Les Anciens Canadiens – not even in translation – which is a pity because I find it the most engaging historical novel in Canadian literature.

It was through

Les Anciens Canadiens that I first learned of Marie-Josephte Corriveau –

la Corriveau – who was executed in April 1763 for the bloody murder of her second husband, Louis Étienne Dodier. Her corpse was subsequently suspended roadside in a gibbet (left). Just the sort of thing that would've caught the attention of this high school Hammer Horror fan.

La Corriveau owes her presence in the novel to José Dubé, the d'Haberville's talkative trusted servant. Tasked with transporting Jules and his "brother de Lochiel" Archie from the Collège to the seigneury, he entertains with legends, folk stories, folk songs, and tall tales. José's story about la Corriveau has nothing to do with the murderess's crime, rather a dark night when "in her cage, the wicked creature, with her eyeless skull" attacked his father. This occurred on on the very same evening in which his dear père claims to have encountered all the damned souls of Canada gathered for a witches' sabbath on the Île d'Orléans (also known as the Île des Sorciers). Says José: "Like an honest man, he

loved his drop; and on his journeys he always carried a

flask of brandy in his dogfish-skin satchel. They say

the liquor is the milk for old men."

|

Seigneur d'Haberville [Les Anciens Canadiens]

Phillipe Aubert de Gaspé [trans Georgians M. Pennée]

Toronto: Musson, 1929 |

Les Anciens Canadiens is unusual in that José and other secondary characters are by far the most memorable. We have, for example, M d'Egmont, "the old gentleman," who was all but ruined through his generosity to others. The account of his decent, culminating in confinement in debtors' prison, is most certainly drawn from the author's own experience. And then there's wealthy widow Marie, "witch of the manor," who foretells a future in which Archie carries "the bleeding body of him you call your brother."

The dullest of we high school students would've recognized early on that Archie and Jules' friendship is formed in the decade preceding the Seven Years' War. The brightest would've had some idea as to where things will lead. The climax, if there can be said to be one, has nothing to do with the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, rather the bloodier Battle of Sainte-Foy.

Not all is so dark. Aubert de Gaspé, born twenty-six years after the fall of New France, makes use of the novel to record the world of his parents and grandparents: their celebrations, their food, and their games ("'does the company please you,' or 'hide the

ring,' ''shepherdess,' or 'hide and seek,' or 'hot

cockles'"), while lamenting all that is slipping away:

In The Vicar of Wakefield Goldsmith makes the

good pastor say:

"I can't say whether we had more wit among us than

usual, but I'm certain we had more laughing, which answered the end as well."

The same might be said of the present gathering,

over which there reigned that French light-heartedness

which seems, alas, to be disappearing in what Homer

would call these degenerate days.

Les Anciens Canadiens is so very rich in detail and story. Were this another country, it would have been adapted to radio, film, and television. It should be assigned reading in our schools – both English and French. My daughter should know it. In our own degenerate days, she should know how to make a seigneurial manor house out of popsicle sticks.

Object: Typical of its time. As far as this Canadian can tell, what's depicted on the cover is the Cameron tartan. The frontispiece (above) is by American illustrator H.C. Edwards.

The novel proper is preceded by the translator's original preface and a preface written for the new edition.

Twelve pages of adverts for other L.C. Page titles follow, including Roberts'

The Story of Red Fox,

Barbara Ladd,

The Kindred of the Wild,

The Forge in the Forest,

The Heart of the Ancient Wood,

A Sister to Evangeline,

By the Marshes of Minas,

Earth's Enigmas, and his translation of

Les Anciens Canadiens.

Access: Les Anciens Canadiens remains in print. The first edition, published in 1863 by Desbarats et Derbyshire, can be purchased can be found online for no more than US$150.

First editions of the Roberts translation, published as

The Canadians of Old (New York: Appleton, 1890), go for as little as US$28.50.

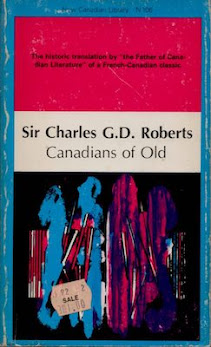

In 1974, as

Canadians of Old,

it was introduced as title #106 in the New Canadian Library. This was the edition I read as teenager... and

the edition I criticized in middle-age. Note that the cover credits the translator, and not the author:

That said, the NCL edition is superior to Page's 1905

Cameron of Lochiel – available online

here thanks to the Internet Archive – only in that it features

Aubert de Gaspé's endnotes (untranslated).

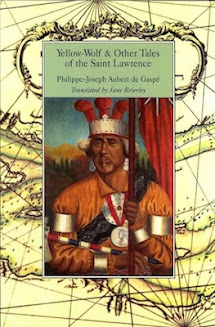

Les Anciens Canadiens has enjoyed three and a half translations. The first, by Georgians M. Pennée, was published ion 1864 under the title The Canadians of Old. It was republished in 1929 as Seigneur d'Haberville, correcting "printer's errors" and "too literal translation." Roberts' translation was the the second. The most recent, by Jane Brierley, published in 1996 by Véhicule Press. is the only translation in print. It is also the only edition to feature a translation of the endnotes.

Lester B. Pearson School Board take note.

Related posts:

.jpg)