Blaze of Noon

Jeann Beattie

Toronto: Ryserson, 1950

353 pages

Good thing I didn't read it before the novel; it would've put me off.

Blaze of Noon begins in fictitious Weldon, Ontario, a community almost certainly based on St Catharines, the author's hometown. Young reporter Jan Fredericks, the narrator, meets even younger reporter Reed Alexander, and a friendship is struck. Both work for the Banner, Weldon's only newspaper. Snide copy boy Tommy suggests that the two gals wouldn't have their jobs if not for the war.

He's probably right. Both were hired to fill in for guys fighting overseas.

Reed tires of the constraints of a small Canadian city and looks to New York where a friend offers a job working for the British Government. Reed is certain that she can get Jan in too, and so the pair purchase train tickets for Grand Central Station.

Jan and Reed find a flat in Greenwich Village, adopt a stay cat, and attend parties populated by people who are considered good connections. They date and sometimes double-date Tim and Pete, two thirty-somethings who are both fifteen years their senior. Nothing is made of the age difference.

Blonde-haired, blue-eyed Reed, the more attractive of the two girls (this according to Jan), begins the novel as something of an ice queen. In Weldon, she's followed about by many men, the most devoted puppy being Richard Campbell, RCAF:

We heard later he had been killed in his first bombing mission. When I told Reed she sat silently in the chair, her body rigid, her eyes deepened to black and her face white. "Poor baby," she said "poor baby."

An unanticipated thaw sets in when Reed meets tall RAF officer Lauri Conroy. She's smitten, even though he treats Reed much as she'd teated her admirers. Eventually, Lauri returns to Europe, leaving her very weepy. On the rebound, Reed lands on moody John Schaeffer. When he comes out as a communist, the slow-moving story shifts to a stuttering crawl as Jan, Reed, Tim, Pete, and John discuss political philosophy and theory. They do this in letters, at restaurants, at parties, at each other's flats, on the street, and atop 30 Rockefeller Center. Really, the dialogue isn't much different after John is introduced, there's just more of it. Consider this early example, from Jan and Reed's first double-date with Tim and Pete:

Is it any wonder that Tim and Pete are bachelors?

The most interesting and atmospheric passages in the novel involve Jan and Reed's early days in New York, but like everything else, descriptions of the city and its culture soon give way to conversations about communism. The worst of it comes when Jan, Reed, Tim, and Pete visit to a "celebrated live joint on Second Avenue where one might hear the pure jazz." Once seated, they offer a tired-looking elderly man a place at their table. No jazz "enthusiast," he'd entered the club only to warm up. He too has thoughts on communism, which is shared over the course of six pages.

Here are two. Feel free to skip. There will be no test.

|

| cliquez pour agrandir |

And the band played on.

It's all so exhausting. Dinner parties are ruined by page after page of back and forth bickering between John, the communist, and Jan, the champion of liberalism. Reed is too late in standing up to it all:

"Let's not talk about Communism or Democracy or any other political belief any more. You two argue, but you never convince each other. So... let's just stop talking about it."

Yes, stop. Please. Please, stop.

But it doesn't stop, dragging on long after John and Reed are through. After their break-up, Pete invites Jan, Reed, and Tim to yet another dinner at his apartment. "I take it," Reed says, "that we are to talk Communism."

"More intellectualizing?" Tim said with a yawn.

"Who's intellectualizing? Pete's eyebrows lifted. "Although I was thinking of the last conversation we had before this fireplace.

"That's right," Tim took out his pipe and began to fill it.

"We settled it all nicely as I recall. There were some high-flown phrases I still don't get, but we tied up things. Now what shall we discuss? Books? The theatre?

"Certainly not," Pete dug deeper into his chair. "As I recall we approached it from a psychological angle."

"Approached it, " Tim groaned, "All right Socrates, make with the words. Don't leave us hanging..."

And yet Socrates couldn't say whether Hades was real.

Blaze of Noon was Jeann Beattie's first novel. Published when she was twenty-eight, it reads like the work of an even younger writer, less seasoned writer. It captures something of the curiosity and earnestness of youth, but little of its passion. Books? The theatre? Do any of these people have no interests outside political philosophy?

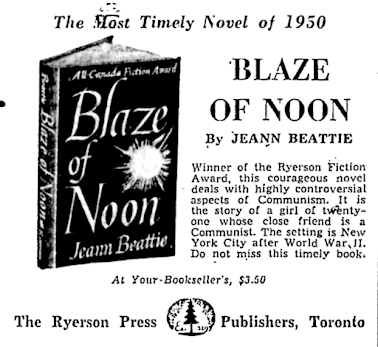

The front flap of the Ryerson edition – there was no other – promoted Blaze at Noon as "the most gripping story of 1950." The publisher's newspaper adverts describe it as the most timely:

|

| Regina Leader-Post, 21 October 1950 |

Strangers on a Train is the most gripping story of 1950.

Given last month's leak in the republic to the south, the most timely novel of 1950 may be

Margaret Millar's Do Evil in Return.

How I wish it was otherwise.

Object: A bulky hardcover. The dust jacket design is uncredited. Its rear flap, listing past winners of the Ryerson All-Canada Fiction Award, is nothing less than depressing.

Access: Held by Library and Archives Canada, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, the Kingston-Frontenac Public Library, and six of our academic libraries. As of this writing, one copy – one – is listed for sale online. A Very Good copy lacking dust jacket, at US$15.00 it seems a deal.