Lee Johnson [Lilian Beatrice Johnson]

191 pages

We begin with what is perhaps the worst first sentence of any Canadian novel:

The windshield wipers were having a hard time battling the weight of wet snow driving against the glass; shh-klip ... sh-sh-klip ... shh-hh-kl-ip ... sh-shh-kl-i-p ... k ...kli ... i ...p ...No complaints about the second sentence ("The snow won."), though the third is nearly as bad:

With a disheartened sh-shh they both stopped, making protesting klips at intervals like maiden aunts with the hiccups, then sliding to rest with a despondent sigh.And so, the reader is left with an obvious choice: soldier on or get out with little investment.

I was disappointed.

The narrator is Scott Royale, a medical doctor who has been handed a second chance. The poor man is clearly emerging from a rough patch and is understandably reluctant to provide backstory. What little can be pieced together runs like this: Scott was married to a woman who left him for another man, he found solace in the bottle, then struggled with the bottle until he was pulled away from the fight by close friends.

Scott has family in the form of his sweet supportive sister Penny, who has encouraged him to resettle in Shelton, a northern town in which she clerks for the local police detachment.

Penny installs Scott in the dead doctor's house, which I'm guessing is owned by the town, and sets to work on redecorating. Meanwhile, her brother sets out on his rounds.

As suggested by the title, cover illustration, and front flap, the novel is a murder mystery, It is also one of those murder mysteries in which a character (in this case, Scott) tells another (Penny) that they are not in a mystery novel.

And so, as men follow Bruton in dying suddenly and unexpectedly, it takes the new doctor a good while to suspect that anything at all is amiss.

Some readers may be frustrated. How can Scott be so blind?

In the meantime, Scott has begun work on a novel, which he describes as:

Nice light detective fiction. Hero only normally immoral; a sultry blonde swaying through his office offering whatever he wants plus a few thousands to prove that she's been bilked out of her lawful rights; a couple of gory corpses; an unintelligent police officer and so forth and so on...Author Lee Johnson deserves some credit here in having Scott reimagine the recent deaths as murders for his novel. In doing so, he realizes that they were in fact murders.

The last scene is short, unexpected, and very good.

That last sentence is perfect.

Trivia (not really): If I haven't already, I spoil things somewhat in revealing that the spark for the spate of murders involves a woman who, suffering from hay fever, confuses two similarly named women. As if to bolster the idea that such a thing is possible, the novel features a nurse surnamed Pennington-Jones, who prefers to be addressed as "Matron" and a character whose surname is Marton. The pages in which the too interact demand careful reading. Manton is a neighbouring community.

About the author: There's not much to share. Lee Johnson (née Lilian Beatrice Johnson) is yet another mid-twentieth-century Canadian author who was published in the UK, but not in her own country. I've yet to find any recognition of the author in a Canadian newspaper or magazine.

The 1931 census records twenty-seven Lilian Johnsons, ranging in age from eight months to fifty-seven years. Was one of them the author?

Medallion (London: Gifford, 1962)Four novels in five years... and then nothing?

Keep It Simple (London: Gifford, 1963)

Heads for Death (London: Gifford, 1966)

Murder Began Yesterday (London: Gifford, 1966)

A subject for further research.

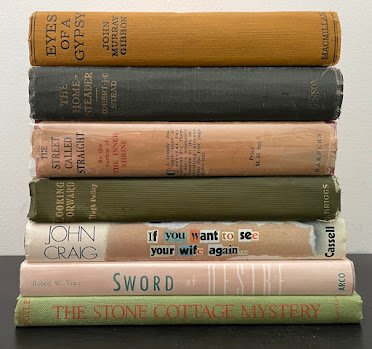

Object and Access: A hardcover in yellow boards, I don't see that there was a second printing. The jacket artist is uncredited. Interestingly, the man depicted is not Scott, rather a secondary character. I believe that is meant to be Scott on the spine.

Four copies, all with dust jacket, are currently listed for sale online. Boy, are they cheap! Expect to pay between $9.94 and $15.15.

My copy was purchased online this past spring from a UK bookseller. Price: £7.00.