The Long November

James Benson Nablo

New York: Dutton, 1946

I'm going to step out on a limb here and state, with confidence, that this was one of the most popular Canadian novels published after the Second World War. Evidence? I can offer nothing more than its publishing history, which over six years included three Dutton printings, two News Stand Library editions and a very attractive Signet paperback. And yet, we remember nothing of James Benson Nablo; The Long November, his only novel, has been out of print for over five decades.

Nablo's narrator is Joe Mack, a wounded, unarmed Canadian soldier hiding from Nazis in a half-destroyed Italian home. Don't be fooled, this is not a war novel, but Horatio Alger's nightmare. As Joe waits out the enemy, he looks back on his 34 years, playing particular attention to his efforts to make something of himself. It isn't that Joe cares so much about money, rather he sees it as a means of winning the love of his life, beautiful blonde Steffie Gibson. Like Duddy Kravitz, who would follow, Joe realizes his riches by "borrowing" the last bit of money he needs to achieve his dream – and, as with Duddy, he loses the girl as a result.

The Long November is a rough book, told in a style that resembles tough guy film noir narration; only Nablo uses words that would not pass the Hays Code. In a 1949 letter to Jack McClelland, Earle Birney provides a list: "Jesus Christ, Christ Almighty, By Jesus, for Christ's sake, goddamit, Bugger all, sonofabitch, suck-holing, stumblebum, crap, shacked up, quickie, a lay, shove it up your keister, tired of being screwed-without-being-kissed." May I add that in one of his many moments of self-recrimination Joe describes his work as "of much use as a tit on a spinster"? Writing in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, John D. Paulus complained: "If this is modern 'realistic writing,' this reviewer will take vanilla."

And I'll take Rocky Road.

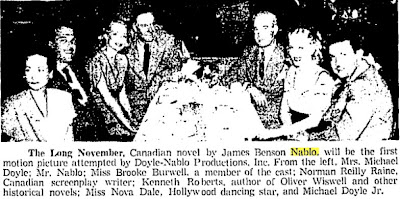

Nearly everything that's been written about Nablo is found on the book's dust jacket. Other references to the author are precious and few. In Imagining Canadian Literature, editor Sam Solecki provides nothing more than a fleeting footnote, referring to "J.V. Nablo [sic] (b. 1910)", an author who has not "been traced". Nablo was indeed born in 1910, making him exactly the same age as his protagonist. Here the future author is recorded in the 1911 census, as the daughter of George and Margery Nablo of 8 Centre Street in Niagara Falls.

I've found little else, though I can say that he never published another book. It seems Nablo left the world of letters for a life in film. In 1954, his short story "The Wheel Man" was adapted by a young Blake Edwards as Drive a Crooked Road. The flick has Mickey Rooney as an honest auto mechanic who finds himself driving the getaway car in a bank robbery. Blame it on a dame.

The god-awful A Bullet for Joey (1955) followed. Of the films made from Nablo's stories, it's by far the most interesting. Why? Well, for one it stars Edward G. Robinson as a French Canadian RCMP detective named Raoul Leduc. Need more? It's a Cold War thriller set in Montreal, and features George Raft as an American mobster who is hired by the Reds to kidnap a nuclear scientist. Who can resist?

A Bullet for Joey was followed by a forgotten western, Raw Edge (1956), which starred Vancouver beauty Yvonne de Carlo (née Peggy Middleton). One wonders whether Nablo lived to see it; industry reports from the autumn of 1956 refer to "the late James Benson Nablo".

The writer's executor seems to have had a busy time of it, selling options for Nablo stories like "Morning Star", which was to have been James Cagney's directorial debut. In the end, there was only one more film: a Victor Mature vehicle entitled China Doll (1958). Its release coincided with a "novelization by Edgar Jean Bracco of a screenplay by Kitty Buhler". Published as a 35¢ Berkley paperback, it makes no mention of James Benson Nablo.

Object: A fairly slim hardcover in green cloth with light brown lettering. What makes the book interesting is that Dutton changed covers for the second and third printings – both in March 1946 – replacing the battlefield landscape with an image of Steffie Gibson looking like a well-covered streetwalker.

Access: Fourteen copies are held in Canadian public and university libraries. It seems that the uncommon first edition exists only in rotten condition. The best copy currently listed online is a bargain at C$30; others lack dust jackets or are ex-library. Decent copies of the News Stand and Signet editions can be had for under C$10. I've yet to come across the 1957 Double Flame paperback.