The Invisible Worm

Collected Millar: The First Detectives

Margaret Millar

New York: Syndicate, 2017

We had a very Canadian eagerness to make something of ourselves.

— Kenneth Millar, 1971

The cover of this most recent volume in Syndicate Books'

Collected Millar suggests that Paul Prye was the author's first detective, when the distinction really belongs to William Bailey. The novel opens with his sister, Amanda, being awoken in the wee hours by a disturbing phone call. A woman named Eve Hays has found a dead man in her stairwell – heart failure, she thinks. An indignant Miss Bailey suggests that a call an undertaker, and not the Inspector of the Mertonville, Illinois, police department, would've been more appropriate. A few minutes later, Miss Hays phones back to apologize for her little joke, confessing that she'd had too much to drink.

Then a body turns up in the lake behind the local country club.

Because Mertonville hasn't seen a murder in many a year, Bailey recognizes that the call is no coincidence, and heads over to the Hays residence. The house is never described, but we know it's very large because it serves as residence to no less than fifteen people, including a butler, a cook, a housekeeper, a maid, and a chauffeur. Eve, the girl who made the call, is the daughter of George and Barbara Hays, who own the digs. Christopher Wells, Eve's fiancé, is a frequent houseguest, and stayed over on the night of the murder. Richard Vanstone, second cousin to Barbara, is firmly installed, as is a woman named Angela Breton, who looks to be making a play for Simon, Eve's nineteen-year-old brother. George Hays' junior partner Peter Morgan and his newly wed wife Sally nearly complete the household census, but there is one more: psychologist Paul Prye, who George has been brought in to diagnose his somewhat unstable wife.

I found Prye irritating from beginning to end. This exchange with Bailey comes at that beginning:

"You are a physician?"

"Well, more or – Yes, I am. But my practice for the last ten years has been in the field of mental abnormalities: neurology, psychoneurology, abnormal psychology, psychoanalysis. I'd rather be called a quack, however. It puts people at ease."

"But you have a medical license?"

"A medical license, a dog license, a driver's license. I even bought a marriage –.

"You are whimsical, I see," the inspector said dryly.

"Yes, indeed.

"The angel that provided o'er my birth

Said, 'Little creature formed of joy and mirth...'

So you see how I stand."

I like Blake as much as the next guy – perhaps more – but Prye's habit of quoting the great man irritated. The humour, lighter and less sophisticated than in Millar's other novels, infects the dialogue, as in this interview between Bailey and the Hays family butler:

"Name, please," he said sternly.

"Joseph Butler."

"Joseph Butler?"

"Joseph Butler," Joseph repeated firmly.

"Sure, it's possible, Chief," Sergeant Abbott said eagerly. "I knew a broad once who was called Broad!"

"A most striking analogy, Sergeant, but this is hardly the time for amorous reminiscences." Bailey turned to Joseph. "Now, Joseph, I'd like to point out to you that it is your duty to lay whatever information you may have before the police, even though it may seem to be damaging to your employers. I appreciate your loyalty but I must have truth."

An upstanding man with little time for nonsense, Bailey initially seems the very model of what one would want in a detective. However, as things progress, we come to recognize serious lapses in judgement, the most obvious being his acceptance of Prye's intrusion in the investigation. Bailey's biggest mistake is to place those living in the Hays' residence under something resembling house arrest. Ignoring the legality of the edict – Millar does – this doesn't prove in the least bit effective; in fact, the body count increases as a result. One character collapses from a poisoned

digestif, while another is found dead in the kitchen pantry.

Bon Appétit!

The Invisible Worm was Margaret Millar's debut, but it's not the place for the uninitiated to begin – that would be

An Air That Kills (1957). I can't quite bring myself recommend this novel, putting me at odds with the reviewers of its day, but there's enough of the writer Millar would become to make it worthwhile to her admirers.

For example, I saw something of future Millar characters in Amanda Bailey, the inspector's sister. Like the aptly-named Prye, she interferes in the investigation, but only with the best intentions. Amanda is certain that a woman will confide in another woman before any man, and so sets out to visit the victim's widow. She plans to present herself as "a representative of the ladies of the Presbyterian congregation," blind to the fact that the widow, Dolly, is an adulterous former burlesque performer.

I was sorry that Millar didn't do more with Angela Breton, Simon's love interest. At thirty-four, the houseguest does all she can to appear younger by dying her hair and hiding the fact that she holds a degree in medicine from the University of Toronto. For reasons that aren't fleshed out, Angela (née Anna) also hides the fact that she is French Canadian.

The Invisible Worm has some workhorse passages – more than any I've encountered in a Millar novel – but there is also wonderful writing, like these opening sentences:

Mr. Thomas Philips smiled happily. Not every man can afford to retire at the age of forty-five; in fact, not every man in Mr. Philips's business lived to that age, The mortality rate in certain professions tends to be high, and Mr, Philips was planning an extended trip to South America.

There was nothing of malice in his smile. He intended to retire gracefully. Old grudges were forgotten, and the past was a lucrative, even a pleasant, memory.

He made an excited little gesture with his hands. He was going away and he was never coming back, and it was rather nice to be saying good-by to someone. Tomorrow, Mr. Philips explained, he and Dolly would be on their way, perhaps on the water by this time. It was very late, and he was tired. He scarcely felt the pinprick on his neck, and by the time the hand closed over his mouth it was too late to do anything about it.

The pinprick and the hand... South America.... Dolly... and Mr. Philips's heart stopped beating.

Before

The Invisible Worm, the earliest Millar I'd read was

Wall of Eyes (1943). A remarkable novel, written with a sure hand, it could have been included in the

Collected Millar volume that Syndicate titled

The Master at Her Zenith.

It's that good.

To think that

Wall of Eyes, her fourth, was published just two years after

The Invisible Worm. Recognizing this, I'm looking forward to reading Millar's second and third novels –

The Weak-Eyed Bat (1942) and

The Devil Loves Me (1942) – even if the publisher describes them as "The Paul Prye Mysteries."

Trivia I: The Invisible Worm was written in response to a challenge from husband Kenneth; it was he who came up with the basic idea. The Doubleday, Doran contract lists the couple as co-authors.

Trivia II: In establishing Bailey's character, Millar writes that the detective was irritated by his sister's gift of a book titled

Keeping Fit at Fifty for his forty-seventh birthday. No such book exists, though a much-referenced and much-reprinted Samuel G. Blythe article with that title was published in the January 15, 1921 issue of the

Saturday Evening Post.

Object and Access: A bulky, 541-page tome printed on substandard paper. The type is small, as are the margins, and yet I'm happy to own a copy. I'd wanted to read

The Invisible Worm for years, but it was inaccessible. The first edition, published in 1941 by Doubleday, Doran, enjoyed just one printing. Unlike most Millars, there has never been a mass market paperback. Apart from the Doubleday Doran, the only other time it appeared in the United States was as a Chivers large print edition.

The first and only UK edition, published in 1943 by John Long, misspells Millar's surname on the dust jacket (but not in the book itself). Uncommon, an Australian bookseller is offering a copy (left) at US$650.

Well worth the price, I say! Librarians, particularly those involved in rare books, are asked to take note of the seller's card. Strike now, before it disappears!

Library patrons will find

The Invisible Worm difficult to access; Library and Archives Canada and the University of Toronto have copies of the Doubleday, Doran first, but that's it. I can't find one listing for

Collected Millar: The First Detectives in a Canadian library – including that serving Kitchener, Ontario, Margaret Millar's hometown.

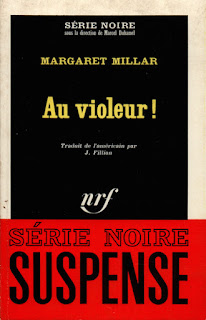

L'invisible ver, a French translation by Laurence Kiefé, was published in 1996 by Librairie des Champs-Elysées. Its cover is nowhere near as interesting as the attractive, if inept, 1943 John Lang edition.

Related posts: