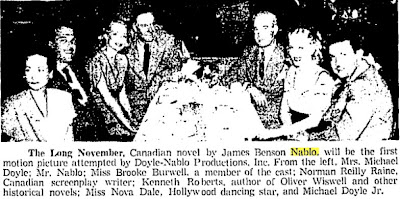

The only image I've been able to find of the Hollywood James Benson Nablo – and don't it look like crap. Blame attendees of the 1936 American Library Association's annual meeting and their enthusiastic endorsement of microfilm.

Published in the 11 May 1946 edition of the Globe and Mail, it has no article attached, so I can't begin to speculate as to why The Long November was never filmed. That said, is it not odd that the project is described as "the first motion picture attempted by Doyle-Nablo productions [emphasis mine]"? And don't the Doyles seem such an unhappy couple? Mrs Doyle looks to be scanning the room for the exit.

But co-producer Nablo is all smiles, as are the others around the table:

Brooke Burwell, who fits Nablo's description of Steffie Gibson to a tee, is a bit of a mystery woman. It appears she never made a film, and has not, to use another's terminology, "been traced".

Kenneth Roberts was a prolific writer, who had a number of forgettable films adapted from his equally forgettable historical novels.

Norman Reilly Raine was really an American, though he did work as a Toronto newspaperman, and later served in the Canadian army during the First World War. At the time this photo was taken, the 51-year-old would have been enjoying success for his adaptation of John Hersey's A Bell for Adamo (1945).

Raine's longtime flame, "Hollywood dancing star" Nova Dale, had one uncredited role as a chorus girl in 1951's Showboat. She died the following year, at the age of 31, several days after smashing up her car.

All this leads to Drive a Crooked Road (1954), which would be the first film based on a Nablo story. These nice, clear images from the trailer, point to a movie that is nowhere near as interesting as what is promised; evidence that promotion hasn't really changed all that much in the past half-century.

Finally, as part of the National Poetry Month promise, another James McIntyre poem. "Niagara Dry" recounts the day – 30 March 1848 – when both the Canadian Falls and its bland cousin ran dry. Nablo grew up just over a kilometre from the falls, practically across the street from where the Ripley's Believe It or Not Museum stands. Culture.

NIAGARA DRYIt happened once in early spring,While there did float great thick ice cakes,That then a gale did quickly bringThem all down from the upper lakes.And Buffalo to Lake Erie,Across the entrance to river,It was a scene of icebergs dreary,Those who saw it will remember ever.The gale blew up lake and river,And left Niagara almost dry,This a lady did discoverAs above the Falls she cast her eye.Such scene it had been witnessed never,Since Israelites crossed the Red Sea,When they had resolved foreverFrom Pharaoh's bondage to flee.Lady she resolved to venture,Proudly carrying British flag,Erected it in river's centreIn crevice of a rocky crag.It seems like a romance by Bulwer,How she captured Niagara,But it was seen by Bishop Fuller,Who did at sight of flag hurrah.Ten thousand years may die away

Before another dry can tread,In bottom of Niagara,For she doth jealous guard her bed.But ice her entrance did blockade,And wind it kept the waters back,So that a child could almost wadeAcross the brink of cataract.

Related posts: