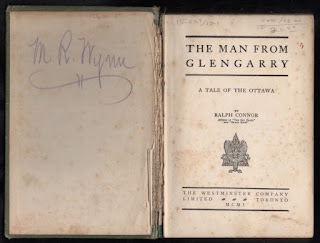

The Man from Glengarry: A Tale of the Ottawa

Ralph Connor [pseud. Rev. Charles W. Gordon]

Toronto: Westminster, 1901

I think it likely that my paternal grandfather had a complete collection of Ralph Connor's novels. Uniform in size, but not in design, they took up the bottom shelf of the largest bookcase in the family home. My father inherited the books, but a decade or so after his death my mother donated the lot to our church's annual rummage sale. She offered them to me beforehand, but I was a teenager; family history and Canadian literature were nowhere near so interesting as Low or the tall Icelandic girl who was in the grade below mine.

Four decades later, family history and Canadian literature obsess. Sixteen Connors sit on my shelves, including two editions of Glengarry School Days and signed copies of The Major and The Prospector.

I have rule when it comes to collecting Connor: I pay no more than two dollars. The Man from Glengarry didn't cost me a thing. I rescued it from a pile of books that were to be stripped of their covers and pulped. The thing is in rotten shape. At some point in its past, an anonymous bookseller identified it as a first edition and hoped to sell it for twenty dollars. I'm betting he didn't.

The Man from Glengarry may be Connor's longest book – at 473 pages it's certainly the longest of those I own – but then the author has a lot to say. This is a novel with a message. It was to Presbyterian aspirations what Antoine Gérin-Lajoie's Jean Rivard novels were to the Catholic. The Preface is essential reading:

There are many men from Glengarry, but the one who takes centre stage is Ranald Macdonald, lone son of ill-tempered lumberman Black Hugh. A boy in the opening pages, young Ranald bears witness to his father's bloody, ultimately fatal, beating by Louis LeNoir of the Murphy gang. The mid-nineteenth-century timber trade is dangerous place, but its gloomy forests are brightened by the Word of the Lord, as brought by Mrs Murray, wife of the local Presbyterian preacher. There is no more accurate word than "saintly" to describe this woman. Mrs Murray

is flawless, which means she is also two-dimensional. What makes her interesting is that she is modelled on Connor's dear mother, a highly-educated, sophisticated woman who devoted herself to her husband and his ministry.

It is through Mrs Murray's guidance – and not, tellingly, that of the flawed Rev Murray – that Ranald grows to become the most intelligent and virtuous of young men. Ultimately, his principles cost him both a partnership in a lumber company and the hand of Maimie St Clair, the woman he has loved since boyhood. However, we know our Father, who seeing what is done in secret, will reward him (see: Matthew 6:4).

This tale of the Ottawa is a good one. I found myself caught up in the struggles between rival gangs and the final days of the romance between Ranald and Maimie. The only eye-rolling moments come at the last chapter, which sees Ranald meeting with Sir John A. Macdonald (no relation, one presumes) to press the importance of the national railway in keeping British Columbia in the federation. The scene brought to mind René LaFlamme, the young hero of Connor's War of 1812 novel The Runner, who kills the man who killed Brock, rescues Laura Secord, etc, etc. "I have heard a great deal about you," Lady Mary Rivers says to Ranald. "Let me see, you opposed separation; saved the Dominion, in short."

So many novels are weakened by their final chapters.

"It is part of the purpose of this book to so picture these men and their times that they may not drop quite out of mind," Connor writes in his Preface. In this, he succeeds. The Man from Glengarry gives a good sense of what Glengarry was like in the day. While it doesn't have anything like the readership it once had, but it remains in print, continues to be studied. More than this, through Mrs Murphy, it has kept the memory of his mother alive.

Family, you understand.

I would appreciate hearing from anyone who has Ralph Connor books bearing the signatures of Edward Busby or Maurice John Busby.

Bloomer:

"What a wonderful boy he must be, Hughie," said Maimie, teasing him. "But isn't he just a little queer?"Dedication:

"He's not a bit queer," said Hughie, stoutly. "He is the best, best, best boy in all the world."

Trivia: As an adolescent, the author attended Ontario's St Marys Collegiate Institute, which sat on the property that borders ours. Until this summer, when the 141-year-old structure was torn down, I could see it from my desk.

Object and Access: First edition? I'll take the unknown bookseller's word for it, though I've seen variants in colour of cloth. The American first edition was published by Revell. The first British edition came from Hodder & Stoughton.

I'm pleased to report that pretty much every academic library in the Dominion and more than a few public libraries have it in their collections.

The Man from Glengarry is currently in print as part of the moribund New Canadian Library, but you'd be better off buying a used copy. Connor claimed that the novel sold five million copies (and here I remind you that he was a clergyman). Hundreds are listed online, starting as low as one Yankee dollar.

Pay no more than two Canadian dollars.

Related post: