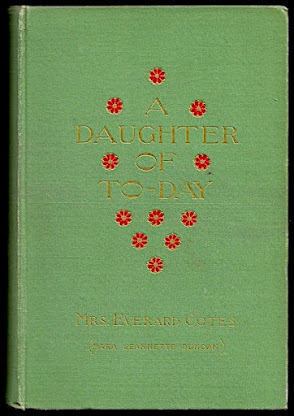

Mrs Everard Cotes (Sara Jeannette Duncan)

New York: Appleton, 1894

Miss Kimpsey's own parlour was excrescent with bows and draperies. "She is above them," thought Miss Kimpsey, with a little pang.

When told of this, Mrs Bell hides disappointment in learning that the Rousseau quotation wasn't in the original French.

Elfrida Bell, daughter of to-day, doesn't feature in the first chapter; she is only as others see her... No, that's not right. During their meeting, Mrs Bell presents Miss Kimpsey with a cabinet photograph for which Elfrida "posed herself." The girl is seen as she wants to be seen.

Fairly beautiful and somewhat talented, Elfrida is easily the most graceful and artistic fish in Sparta's small pond. An aspiring painter, she's enrolled in a Philadelphia art school. When results don't meet Mr and Mrs Bell's expectations, Elfrida is sent to study under Monsieur Lucien in Paris. Sadly, her Hungarian cloak draws more notice than her work.

Elfrida was certain that if she might only talk to Lucien she could persuade him of a great deal about her talent that escaped him – she was sure it escaped him – in the mere examination of her work. It chafed her always that her personality could not touch the master; that she must day-after day be only the dumb, submissive pupil. She felt sometimes that there were things she might say to Lucien which would be interesting and valuable for him to hear.

It is both trite and apt to describe Elfrida as complex. A young woman who lives for art and the life of an artiste, her behaviour can be infuriating. "'I know I must be difficult,'" she says when sitting for English portraitist John Kendal:

"Phases of character have an attraction for me – I wear one to-day and another to-morrow. It is very flippant, but you see I am honest about it. And it must make me difficult to paint, for it can be only by accident that I am the same person twice."

A Daughter of To-Day was read in one go on July 22nd, the hundredth anniversary of Sara Jeannette Duncan's death. It was hard to put down. Writing to-day, I realize it was read too quickly. The more I consider, the more I see – much like Elfrida as she casts a critical eye on her portrait.

Trivia (or not): Sara Jeannette Duncan's mother was born Jane Bell. Elfrida's closest friend is named Janet.

Object: My copy, the first American edition, was purchased earlier this year from a Kentucky bookseller. Price: US$24.95. A thing of beauty, the image above doesn't come close to doing it justice. The novel proper is followed by four pages of adverts for Appleton editions of Rudyard Kipling, Wolcott Balestier, Beatrice Whitby, Egerton Castle, Edward Eggleston, and Maarten Maartens.

Access: First published in 1894 by the Toronto News Company (Canada), Appleton (United States). and in two volumes by Chatto & Windus (Great Britain).

Both the Toronto News Company, and Appleton editions can be read online through the Internet Archive.

The novel was reissued in 1988 by Tecumseh. Print on demand vultures offer this edition.