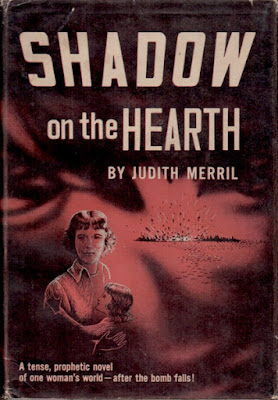

Shadow on the Hearth

Judith Merril

New York: Doubleday, 1950

Westchester housewife Gladys Mitchell is leading the life of June Cleaver. True, there had been struggles in her past – the Great Depression, for example – but things are now going swimmingly. She and husband Jon, a highly successful engineer with his own firm in Manhattan, can take pride in having provided a comfortable family home for their three children. Their eldest, freckle-faced Tom, is in the ROTC. Babsy – she now prefers "Barbara" – has begun putting on airs, but is otherwise an agreeable fifteen-year-old. And then there's Ginny, the baby of the family, an adorable little girl of five whose best friend is a stuffed toy horse.

The novel opens on a day like any other with the family – sans Tom, who is away at school – seated around the breakfast table. But then Veda, the poorly-paid Mitchell family maid, calls in sick. Barbara needs some clothing washing done, which means that Gladys won't be free to attend a ladies' luncheon. Oh, and she'd been working so to be accepted!

Jon leaves for work, dropping the girls at school along the way, and Gladys attends to the laundry. She's down in the basement, hovering over her washer and dryer, when there's a sound that is something like thunder. The light streaming through the window doubles in intensity, then becomes very dull. Dismissing it as "a freak electric storm", Gladys dons a new dress, powder and lipstick. It isn't until after the girls return, courtesy of nice new schoolteacher Miss Pollack, that Gladys comes to realize there has been an atomic attack... Atomic Attack being the title of the 1954 Motorola TV Hour adaptation. The news comes courtesy of the radio:

"For those of you who have just tuned in, we repeat: several atomic bombs of unknown origin landed in and near the harbor of New York City this afternoon. The first explosion occurred at about 1:15 P.M., Eastern Standard Time, and was followed by others over a period estimated to be approximately one half hour. It is know that no bombs were dropped after two o'clock. Eyewitnesses state that the first bomb exploded underwater at the mouth of the East River, affecting harbor shipping in New York and Brooklyn, and substantially damaging a large part of the lower tip of Manhattan Island."

Nearly all 277 pages of Shadow on the Hearth take place in the Mitchell home, which is not to say that things aren't eventful. Early in the crisis, Gladys must deal with troublesome neighbour Edie Crowell, who persists in phoning, despite instructions to leave the lines clear. On the second day, she shows up drunk as a skunk on the front steps.

Can you blame her?

There's a gas leak, which probably has nothing to do with the bombs, but does add to the drama. At another point, thugs try to break in, but are beat back by Dr Garson Levy, the high school's science teacher. Barbara fills her mother in on the doctor's background:

"He knows everything about atom bombs. He was at Oak Ridge and everything… Only he got black-listed or something on account of refusing to do war work, and making a lot of speeches and being on committees, so he had to go be a teacher."Yes, he had to go to be a teacher.

Levy has been running from house to house informing parents that their children have been exposed to radioactive rain. Local Civil Defence officials are in hot pursuit. When the heat becomes to great, Levy is offered temporary refuge in the Mitchell home, filling something of the void left by missing husband Jon. He fixes a toy, boards windows, and devises a clever solution to that pesky gas problem. Gladys comes to think of him as "Mr Fit-It", but he's so much more. Garson Levy comes equipped with personal geiger counter and everything required to monitor the white blood cells of the Mitchell children.

It's all a bit much.

Fortunately other characters are better drawn, the most interesting being Jim Turner. The Mitchell's hard-nosed next-door neighbour, Gladys is surprised to learn that Turner is the leader of the local Civil Defense squadron.

"Well, nobody else knew either," he assured her. "Nobody who wasn't in it. When you want to win you got to keep a poker face and play it close to the vest. And any time the government let out any information about what we were going some scientist would start yelling about warmongers, or some reds would have a demonstration."Turner turns up frequently, revelling in his newfound authority, and doing prep work to put the moves on Gladys. As evacuation looks imminent, he tries to dictate where she will live and what she will be doing. Maid Veda reenters the story, dragged in by soldiers who are investigating whether she is a foreign agent. Neighbour Edie plants the seed that maybe, just maybe, the Civil Defense would prefer people like herself dead. We learn that Peter Spinelli, the young medical doctor who accompanies Turner on his route, was denied funding for his studies because of his association with pacifist groups. The press is censored and then disappears, replaced by government broadcasting that consists almost exclusively of lengthy lists of casualties.

These sinister elements run beneath the surface, overwhelmed by a flurry of activity and the ever increasing challenges faced by the survivors. It's such that a broadcast reference to "the military government" passes without comment. Before anyone has a chance to catch their breath, the war comes to an abrupt end. The news comes over the radio:

"Five thirty-seven A.M., Friday, May seventh,” a hoarse voice intoned. “That is the historic moment. We have just received official news from General Headquarters. The war is over! The enemy conceded at 5:37 A.M., Eastern Standard Time, just five minutes ago. Ladies and gentleman, the national anthem!"As for Jon, he somehow survived the bombs that rain down on Manhattan. In fleeting scenes – vignettes, really – he escapes an infirmary and makes his way to Westchester. Nearing home, he's shot through the shoulder, loses a good amount of blood, and is carried the rest of the way by good Dr Spinelli. Merril's original ending had Jon die. Doubleday wanted a happy ending... so why am I left with the impression that things are only going to get worse?

Object: A first edition of the author's first book, my copy was purchased last year in London at Attic Books. Price: $6.25. The ugly jacket was designed by Edward Kasper, a man whose awkward work I first encountered in the inner gatefold of The Band's Moondog Matinee.

Access: The 1950 Doubleday was followed three years later by Sedgwick & Jackson's first British edition (above left). Remarkably, Shadow on the Hearth has appeared only once in paperback: a 1966, edition published in the UK by Compact Books (above right). It is currently available in Spaced Out: Three Novels of Tomorrow, a collection of Merril's novels published by the New England Science Fiction Association.

There are plenty of first editions listed online, the least expensive being a Good Sedgwick & Jackson at £7.00.

At US$375, the most expensive is a Very Good signed copy of the Doubleday first once belonging to International Festival of Authors' founding Artistic Director Greg Gatenby... but let's not get into that. The bookseller is throwing in a copy of the festival's newspaper tribute to Merril signed by Samuel Delany, Michael Moorcock, Frederick Pohl, Spider Robinson and the lady herself. I recommend the Fine signed copy being offered by a Michigan bookseller. Price: US$87.00.

A German translation, Dunkle Schatten (Dark Shadows), was published in 1983, complete with cover that looks every bit like it comes from the Reagan Era... because it does. In fact, the enemy is never identified. The Italians did a much better job with the covers on their translation, Orrore su Manhattan (Horror of Manhattan), which has twice seen print (1956 and 1992).

Library patrons will be disappointed. Library and Archives Canada, the Toronto Public Library, and six of our universities have copies.

Related post: