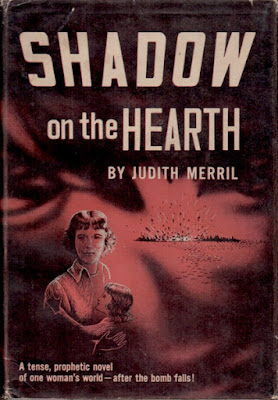

A not-so-brief follow-up to last week's post on Judith Merril's Shadow on the Hearth.

"The title of my book had been chosen by the publishers in preference to about a dozen other titles I had provided, all of which pointed towards the idea of atomic war," writes Judith Merril in her unfinished autobiography, Better to Have Loved (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2002). Was Atomic Attack one of them? I prefer Shadow on the Hearth, just as I prefer her novel to the television adaptation.

Atomic Attack aired on 18 May 1954, as part of the first and only season of The Motorola TV Hour. The director was Ralph Nelson, justly celebrated for the films Requiem for a Heavyweight and Lilies of the Field. So why is this so bad?

Blame lies with writer David Davison's script, though I do wonder whether it was entirely his fault. A New York newspaperman, in 1947 Davidson earned significant praise for his debut novel, The Steeper Cliff. The story of an American serviceman's search for a missing person in post-war Bavaria, it was published in the United States, Britain and Australia (right). Through much of the 'fifties, Davidson made good money writing for Kraft Theater, The Ford Theater Hour, The Alcoa Hour, The Elgin Hour, and The United States Steel Hour, but had become disenchanted by decade's end. Davidson's moment in the spotlight came in 1961, when he appeared before the FCC to testify on the networks' deteriorating standards, which he blamed on the pursuit of ratings. By that time he'd all but given up writing for television. His two remaining decades were spent teaching.

Was Motorola just after ratings with Atomic Attack?

I ask because it ended up with so much more. Cold War historian Bill Geerhart informs that the teleplay was used in Civil Defense instruction and was listed for rent or sale in government catalogues. Indeed, the opening of Atomic Attack sounds every bit like propaganda:

The play you are about to see deals with an imaginary H-Bomb attack on New York City, and with the measures Civil Defense would take in such an event for the rescue and protection of the population in and around the city.Davidson cuts the first two pages of Shadow on the Hearth, in which Veda calls in sick, and begins with the Mitchells – Gladys (Phyllis Thaxter), Barbie (Patsy Bruder), Ginny (Patty McCormack) and Jon (uncredited) at breakfast. It's a short scene, though it establishes all we need to know about the family and the busy day ahead: Jon is off to work, the girls are off to school, the maid is ill, and there's washing to be done.

Cut to the blandest of establishing shots:

Gladys descends the stairs and there is a blinding flash of light. She thinks a blown fuse is to blame, until rocked by a shockwave. Air raid sirens sound.

Extreme overacting follows, though I can't quite bring myself to fault Thaxter, who is stuck delivering this long monologue as she races about the house:

"Air raid? No. No, no, it can't be! Children! Jon! Clouds of smoke! Coming up from the south, from New York! Mrs Jackson! Mrs Jackson, what's happened! Don't you hear me? Oh, please! Is nobody home?"This last bit is yelled out her kitchen window. Gladys rushes through the dining room and living room to the vestibule closet and then the telephone:

"Children at school. Jon! Jon at the office in New York. Oh, New York. New York. Operator? Long distance. No answer. Try the local operator. Operator? Somebody? No answer from anybody! Children. Must get down to school."She throws on her raincoat and is almost out the door when the radio she'd turned on moments earlier comes to life:

"Your attention, please. We interrupt our normal program to cooperate in security and Civil Defense measures as requested by the United States government. This is a CONELRAD radio alert. Listen carefully. This station is now leaving the air. Tune your standard radio receiver to 640 or 1240 kilocycles for official Civil Defense instructions and news. Once again – Your attention, please! Your attention, please! This is your official Civil Defense broadcaster. An explosion has just taken place in New York City, which has believed to have resulted from the dropping of a hydrogen bomb. The bomb was probably carried by a guided missile launched from a submarine at sea! All Civil Defense workers report to emergency stations immediately.""The children!" she cries. Gladys rushes to leave, but stops when she hears this:

Stay where you are, unless you are in immediate danger! Do not attempt to join your children if they are in school! They are being well taken care of where they are! Do not try to telephone! Remember: radioactivity may make food and water in open containers dangerous. Use canned and otherwise protected foods until further notice. Do not attempt to enquire about relatives in New York – as yet there is no information!

It reminded me of nothing so much as an old Gilda Radner sketch.

The remaining forty-three minutes of Atomic Attack – it runs fifty – aren't quite as funny, which isn't to say that they're not worth watching, particularly for readers of the book. After all, Shadow on the Hearth was written by a Trotskyist who would one day relocate to Canada in part because she "could no longer accept the realpolitik of being an American citizen." Atomic Attack strips away all shading and uncertainty, with everyone living under a government that has the situation well in hand. Nowhere is this more evident that in the depiction of Jim Taylor, the Civil Defense Block Warden. Where in the novel he is a nefarious figure who sees the crisis and his new status as a means of manipulating and ultimately bedding Gladys, the Jim Taylor of Atomic Attack (William Kemp) is a by the book, no-nonsense and reliable.

Scientist Garson Levy – rechristened "Garson Lee" (Robert Keith) – has much the same background, but a very different future. As in the novel, he is being pursued by the authorities, but as he discovers this isn't because of his activism; they want him to set up a research project on "radiation exposure and how to deal with it."

Garson should know better than to distrust authority.

A youngish Walter Matthau plays young Dr Spinelli, but nothing is mentioned of his Shadow on the Hearth pacifist background. As in the novel, he takes Ginny to be examined at the hospital, which is here depicted as a calm, professional place with little activity. Ginny aside, the only patient seen is a rambunctious young scamp with a few sores on his face. "They're only important if they're not kept clean," Dr Spinelli reassures.

Other differences have less to do with propaganda than the challenge of cramming a 277-page novel into an Hour that isn't an hour long. Drunken neighbour Edie Cowell is replaced by Mrs Moore (Audrey Christie), one of several homeless people dumped at the Mitchell house by Block Warden Taylor. One of their number, Mrs Harvey (Elizabeth Ross) gives Gladys the opportunity to open up about her concerns for her husband. The scene is interrupted by a phone call from Jon's secretary, who more or less implies the worst. This is the greatest departure. As a reader of the novel, and a viewer familiar with the Hollywood Ending, I fully expected Jon to appear in the closing minutes. This never happens. And, so, a daring, unexpected conclusion.

In Better to Have Loved, Merril writes:

Watching the adaptation was sort of like having a different lens on each of my eyes. One part of me was saying, "They killed my book. They've killed my book." The other part was saying , "But they did the best they could to translate it into television."I wonder about this.

Atomic Attack can be seen today on YouTube. When did Judith Merril last see it? I'm betting decades before her death – and perhaps only once.

Atomic Attack didn't kill Shadow on the Hearth, nor was it the best one could expect from television. The novel has great potential for adaptation today. Imagine a period piece in which it is believed that exposure to extreme radiation is might be cured. Imagine a time when nuclear weapons weren't nearly so numerous or powerful, a time in which most might actually survive all-out nuclear war.

Imagine.

Trivia: Radio broadcasts come fast and furious in both the novel and the Motorola TV Hour adaptation. In the latter, but not the former, Gladys uses Motorola radios to keep abreast of developments.

Product placement.

Related posts: