|

| Never Trust a Woman [In a Vain Shadow] Raymond Marshall [René Lodge Brabazon Raymond] Toronto: Harlequin, 1957 |

14 February 2023

A Ruthless Harlequin Valentine

06 February 2023

A Woman Cheated

The Cannibal Heart

Collected Millar: Dawn of Domestic Suspense

Margaret Millar

New York: Syndicate, 2017

The novel takes place almost entirely on the grounds of a large California oceanfront estate rented by the Banners: Richard, Evelyn, and their active eight-year-old daughter Jessie. The property belongs to a Mrs Wakefield, whose efforts to sell have been thwarted by a draught. Her employees, cook Carmelita and caretaker husband Carl, live with their adolescent daughter Luisa in a three-room apartment above the garage.

Someone spoken of, but not seen, Mrs Wakefield grows as a figure of mystery in the initial chapters. She at last appears as an attractive thirty-something widow worthy of sympathy. In the space of the previous two years, Mrs Wakefield has lost her husband John, as well as Billy, their only child. John was a naval engineer, a wealthy man whom Mrs Wakefield met as a schoolteacher from a small Nebraska town. Their child, Billy, was... well, let's say Billy is revealed gradually.

But then things in Millar novels are always revealed gradually.

As always, Millar delves deeply into the inner lives of its characters, children included. Fifteen-year-old Luisa, a minor character (no pun intended), is a good example. Like most teenagers, she dreams of life far from her parents. In her fantasies, she's a singer with beautiful blonde hair, fawned over by handsome men with lots of money. But this can never happen in the way she imagines. Reality intrudes, reflected in the words of her father, who recognizes that she has been born "half-mulatto, half Mexican."

Syndicate Books, Millar's current publisher, lists The Cannibal Heart as a novel of suspense. It isn't. The Cannibal Heart belongs with Experiment in Springtime and Wives and Lovers, the two (and only two) novels the publisher categorizes as "OTHER NOVELS." As I wrote in a previous review, in these people do bad things; as do we all. While the reader might anticipate murder – after all, Millar was a mystery writer – nothing of the kind occurs. No character commits a criminal act, though one comes close. That that same character is the most sympathetic, most wronged, and most cheated, leads me to wonder whether I'm not right to thinking The Cannibal Heart below average Millar.

"For an old friend, a fine critic, and an ever-imaginative angler, Harry E. Maule."

As might be expected, The Cannibal Heart is uncommon in our public libraries. That serving Kitchener, the city in which Margaret Millar was born, the city in which she was raised, the city in which her father served as mayor, does not have a copy.

The Collected Millar remains in print. Used copies of The Cannibal Heart listed online begin at €6 (a first edition lacking jacket). At US$225, the most expensive is the same edition in "fine, bright dust jacket." Do not read the bookseller's description as there is a spoiler.

The Cannibal Heart has enjoyed two translations: French (Le coeur cannibale) and German (Kannibalen-Herz).

27 January 2023

Television Man is Crazy

The one hundred and twelfth issue of Canadian Notes & Queries arrived in our rural mailbox yesterday afternoon. A beautiful thing, wrapped in a cover by Seth, I've been dipping in and out. I read Michael Holmes' remembrance of Steven Heighton first.

This evening, I'll be reading 'My Year of Mycorrhizal Thinking' by Ariel Gordon, whose daughter shares something with my own as a fan of Hannibal. Ariel, her daughter, and mine, will appreciate this photo taken in our kitchen not eight days ago.

This issue's Dusty Bookcase column focuses on Jeann Beattie's Behold the Hour (1959), which in my opinion ranks with Ralph Allen's The Chartered Libertine (1954) as one of the two best novels set early days of Canadian television.

I'm not aware of a third.

Northrop Frye praised Allen's novel. Do I praise Beattie's?

Read and find out! Subscriptions can be purchased through this link.

Carolyn BennettJames CairnsAndreae CallanaPreeti Kaur DhaliwaiStephen FowlerSusan GlickmanAlex GoodBrett Josef GriubisicGraeme HunterKate KennedyRohan MaitzenDarcy MasonDavid MasonRoderock Moody-CorbettShani MootooIan Clay SewallRudrapiya RathmoreRichard SangerNatalie SouthworthKevin Sprout

16 January 2023

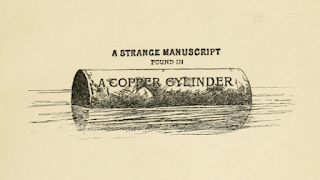

James De Mille's Antarctic Death Cult

[James De Mille]

New York: Harper & Bros, 1888

306 pages

Forty years ago this month, I sat on a beige fibreglass seat to begin my first course in Canadian literature. An evening class, it took place twice-weekly on the third-floor of Concordia's Norris Building. I was a young man back then, and had just enough energy after eight-hour shifts at Sam the Record Man.

The professor, John R. Sorfleet, assigned four novels:

James de Mille - A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder (1888)Charles G.D. Roberts - The Heart of the Ancient Wood (1896)Thomas H. Raddall - The Nymph and the Lamp (1950)Brian Moore - The Luck of Ginger Coffey (1960)

The earliest, A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder, intrigued because it overlapped with the lost world fantasies I'd read in adolescence. Here I cast my mind back to Edgar Rice Burroughs' Pellucidar, my parents' copy of James Hilton's Lost Horizon, and of course, Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World.

De Mille's novel begins aboard the yacht Falcon, property of lethargic Lord Featherstone. The poor man has tired of England and so invites three similarly bored gentlemen of privilege to accompany him on a winter cruise. February finds Featherstone and guests at sea somewhere east of the Medeira Islands, where they come across the titular cylinder bobbing in becalmed waters. Half-hearted attempts are made at opening the thing, until Melick, the most energetic of the quartet, appears with an axe.

Featherstone and company, while civilized, are not the best civilization has to offer. In the days following the discovery, they lounge about the Falcon taking turns reading the manuscript aloud, commenting on the text, and speculating as to its veracity.

More writes that he was a mate on the Trevelyan, a ship chartered by the British Government to transport convicts to Van Dieman's Land. This in itself sounds fascinating, but he skips by it all to begin with the return voyage. Inclement weather forces the Trevelyan south into uncharted waters "within fifteen hundred miles of the South Pole, and far within that impenetrable icy barrier which, in 1773, had arrested the progress of Captain Cook."

No one aboard the Trevelyan is particularly concerned – the sea is calm and the skies clear – and no objections are raised when More and fellow crew member Agnew take a boat to hunt seals. Fate intervenes when the weather suddenly turns. In something of a panic, the pair make for their ship, but efforts prove no match for the sea. They are at its mercy, resigned to drifting with the current, expecting slow death. And yet, they do find land, "a vast and drear accumulation of lava blocks of every imaginable shape, without a trace of vegetation—uninhabited, uninhabitable." A corpse lies not far from the shore:

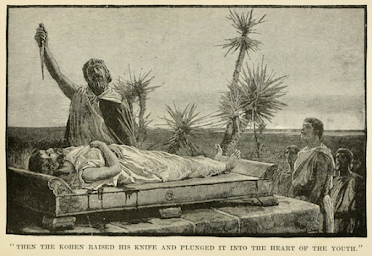

The clothes were those of a European and a sailor; the frame was emaciated and dried up, till it looked like a skeleton; the face was blackened and all withered, and the bony hands were clinched tight. It was evidently some sailor who had suffered shipwreck in these frightful solitudes, and had drifted here to starve to death in this appalling wilderness. It was a sight which seemed ominous of our own fate, and Agnew’s boasted hope, which had so long upheld him, now sank down into a despair as deep as my own. What room was there now for hope, or how could we expect any other fate than this?More and Agnew provide a Christian burial and return to their boat hoping, but not expecting, to be carried to a better place. Whether they find one is a matter of opinion. The pair pass through a channel that appears to have been formed by two active volcanoes, after which they encounter humans More describes as "animated mummies." They seem nice, until they reveal themselves as cannibals. Hungry eyes are cast on Agnew. He's killed and More escapes.

A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder is not a Hollow Earth novel, though inattentive readers have described it as such. More's boat enters a sea within a massive cavern, where he encounters a monster of some sort and fires a shot to scare it off.

The boat continues to drift, emerging on a greater open sea. It's at this point – 53 pages in – that the real adventure begins.

"I was born," said he, "in the most enviable of positions. My father and mother were among the poorest in the land. Both died when I was a child, and I never saw them. I grew up in the open fields and public caverns, along with the most esteemed paupers. But, unfortunately for me, there was something wanting in my natural disposition. I loved death, of course, and poverty, too, very strongly; but I did not have that eager and energetic passion which is so desirable, nor was I watchful enough over my blessed estate of poverty. Surrounded as I was by those who were only too ready to take advantage of my ignorance or want of vigilance, I soon fell into evil ways, and gradually, in spite of myself, I found wealth pouring in upon me. Designing men succeeded in winning my consent to receive their possessions; and so I gradually fell away from that lofty position in which I was born. I grew richer and richer. My friends warned me, but in vain. I was too weak to resist; in fact, I lacked moral fibre, and had never learned how to say 'No.' So I went on, descending lower and lower in the scale of being. I became a capitalist, an Athon, a general officer, and finally Kohen."

"Here," said she, "no one understands what it is to fear death. They all love it and long for it; but everyone wishes above all to die for others. This is their highest blessing. To die a natural death in bed is avoided if possible."The Kohen tells the story of an Athon who had led a failed attack on a creature in which all were killed save himself. For this, he was honoured:

“Is it not the same with you? Have you not told me incredible things about your people, among which there were a few that seemed natural and intelligible? Among these was your system of honoring above all men those who procure the death of the largest number. You, with your pretended fear of death, wish to meet it in battle as eagerly as we do, and your most renowned men are those who have sent most to death.”

Object and Access: All evidence suggests that A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder was written in the 1865 and 1866. It was first published posthumously and anonymously in the pages of Harper's Weekly (7 Jan 1888 - 12 May 1888). My copy, a first edition, features nineteen plates by American Gilbert Gaul. The copy I read as a student was #68 in the New Canadian Library (1969). I still have it today, along with the Carleton University Press Centre for Editing Early Canadian Texts edition (1986). Neither was consulted in writing this review, but only because they're in that damn crawlspace.

The NCL edition is out of print, but the Centre for Editing Early Canadian Texts edition remains available, now through McGill-Queen's University Press. It has since been joined by another scholarly edition from Broadview Press (2011).

Used copies of are easily found online. Prices for the Harper & Bros first edition range between US$65 and US$400. Condition is a factor, but not as much as one might assume. The 1888 Chatto & Windus British first (below) tends to be a bit more dear.

Translations are few and relatively recent: Italian (Lo strano manoscritto trovato in un cilindro di rame; 2015) and Hindi ( एक तांबा सिलेंडर में पाया एक अजीब पांडुलिपि, 2019).

03 January 2023

A Forgotten Mystery; a Shattered Dream

Victor Lauriston

Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1922

292 pages

The Twenty-first Burr is a mystery novel populated in part by characters with assumed names and hidden identities. It begins with twenty-year-old Laura Winright's rushed return to North America after two years touring Europe. I've read enough old novels to know that such a young lady would not have been been permitted to go off alone to the Old World. That Laura did so – and in the midst the Great War – is a mystery left unexplained and unexplored.

"Was she a spy?" asks my wife.

Good question.

Our heroine's haste has everything to do with a telegram sent by her father, Detroit department store baron Adam Winright. Laura never lived in the Motor City, rather she was raised at the family mansion, Castle Sunset, at Maitland Port (read: Goderich, Ontario) on the shore of Lake Huron.

Oh, see here, chick! You've come down on us like the wolf on the fold. We haven't time to send out for crackers and cheese. Of course your father is just fine and dandy. Why shouldn't he be?But Adam Winright is not fine and dandy. By the time Laura reaches Maitland Port, her father is dead.

The worst thing about The Twenty-First Burr is that it shows such promise, yet was Lauriston's only mystery. McClelland & Stewart used the plates from George H. Doran's American edition. Neither publisher went back for a second printing.

Lauriston spent his royalties on buying those same plates. He hoped that they would one day be used in returning the novel to print. An author's fantasy, it ended in 1941 when they were sold for use in the war effort.

|

| The Windsor Daily Star, 21 August 1941 |

The accompanying article – 'Chatham Writer's Dream Shattered After 19 Years' – begins:

Sale of 700 pounds of lead and copper plates in New Britain, Connecticut, recently, put an end to a dream that has lived in the persevering mind of Victor Lauriston, Chatham novelist, ever since he sold his first book 19 years ago. He had hoped sometime to use the plates for a reprint of the book, "The Twenty First Burr," [sic] a detective story.Lauriston lived well into old age, dying two days after his ninety-second birthday, yet he wrote only one more novel. A roman à clef titled Inglorious Milton, according to the Border Cities Star (20 October 1934), it "set every tongue in Chatham wagging." Lauriston's papers hold the manuscript, along with numerous letters of rejection. The novel was finally published by the Tiny Tree Club, a branch (sorry) of Chatham's literary society. I've not read it, but should. The Border City Star article compares it to Joyce's Ulysses.

Metal in the plates will be melted to help win the war. Owing to exchange regulations, proceeds of the sale will go to pay a 16 years' storage bill.

I can only assume society members are portrayed in a flattering light.

Object: Light brown boards with black impressing. The jacket illustration is by Margaret Freeman. My copy once belonged to a woman named Olive Shanks.

At the time of the 1921 census, Miss Shanks, then age 29, lived with her parents (John and Hattie) and siblings (Bessie and Mark) at 146 Park Street, Chatham, Ontario.

|

| 146 Park Street, Chatham, Ontario November 2020 |

In 2019, her copy ended up in my home, having been purchased from bookseller David Mason. Price: $90.00.

Access: The Twenty-First Burr was published by Doran in the United States and in Canada by McClelland & Stewart. Neither edition enjoyed a second printing. As of this writing, two copies are listed for sale online, both from London booksellers: London, Ontario's Attic Books offers a jacketless copy of the Doran edition at US$35.00; London, England's Any Amount of Books is asking £30.00 for its jacketless Doran. The McClelland and Stewart edition is nowhere in sight.

Sixteen of our academic libraries hold copies of one edition or the other, as does Library and Archives Canada.

01 January 2023

31 December 2022

'The Dying Year' by S. Frances Harrison

|

The old year dies! Of this be sure,The old leaves rot beneath the snow.The old skies falter from the blowDealt by the heavens that shall endureWhen sky and leaf together go.And some are glad and some are grieved.Much as when some poor mortal dies;The first sensation of surpriseIs lost in sobs of his bereaved.Or cold relief with dry-dust eyes,That view his coffin absently,And wonder first how much it cost,And next, how came his fortune lost,And how will live his family.And how he looked when he was crost.But tears—no, no—they only surgeFrom those who knew him. They were few;He had his faults; he seldom knewThe thing to say, condemn, or urge;Tis better he has gone from view.So neither do we weep—God knows,We have but little time for tears!A time for hopes, a time for fears,A time for strife, a time for woesWe have—but hardly time for tears.O it were good, and it were sweet.If we might weep our fill somewhere,In other world, in purer air,Perhaps in heaven's golden street,Perhaps upon its crystal stair!For "power and leave to weep" shall beThe golden city's legend dear;Though wiped away be every tear.First for a season shall flow freeThe floods that leave the vision clear!So if we could we would, Old Year,Conjure a tear up when you go,And pace in solemn order slowBehind your gray and cloud -borne bier,Draped with the wan and fluttering snow.Yet what is it, this year we miss?An arbitrary thing, a mark;A rapid writing in the dark;Dead wire, that with a futile hissStrikes back no single answering spark.There is no year, we dream and say,Again, no year, we say and dream,And dumbly note the frozen stream,And note the bird on barren spray.And note the cold, though bright sunbeam.We quarrel with the times and hours,The year should end—we say—when comeThe last long rolls of March's drum.And too—we say—with grass and flowersShould rise the New Year, like to someGay antique goddess, ever young,With pallid shoulders touched with rose,Firm waist that mystic zones enclose,White feet from violets shyly sprung.Her raiment—that the high gods chose.And yet the poet, born to preachWith yearning for his human kind,His verse but sermon undefined,Will fail in what he means to teach,If he proclaim not, high designed,

The Old Year dies! It is enough!And he has won, for eyes grow dimAs passeth slow his pageant grim,And many a hand both fair and roughShall wipe away a tear for him—For him, and for the wasted hours,The sinful days, the moments weak.The words we did or did not speak,The weeds that crowded out our flowers,The blessings that we did not seek.

26 December 2022

The Very Best Reads of 2022: Ladies First

Late last night, as Christmas festivities drew to a close, I pulled Victor Lauriston's The Twenty-first Burr (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1922) from the shelves. It seemed appropriate way to end the holiday. One hundred years earlier, my copy was presented by the author to a woman named Olive Shanks.

This was a year unlike any other in Dusty Bookcase history. For the first time, women wrote a majority of the titles; twelve of the twenty-two reviewed here and in the pages of Canadian Notes and Queries.

Sara Jeannette Duncan's A Daughter of To-day and Joanna E. Wood's The Untempered Wind stand well above the other twenty. Both are available in Tecumseh's Early Canadian Women Writers Series, which goes some way in explaining how it is that only male authors feature in my annual selection of the three books most deserving of a return to print:

Toronto: S.B. Gundy, 1915

It's the stuff of a Leacock story.

As series editor of Véhicule Press's Ricochet imprint, I was involved in reviving Arthur Mayse's 1949 debut novel Perilous Passage. 'Telling the Story,' the introduction provided by the author's daughter, Susan Mayse, is one of my favourite in the series. Reprinted in Canadian Notes & Queries, it can be read through this link.

Recognition this year goes to England's Handheld Press for its reissue of Marjorie Grant's 1921 novel Latchkey Ladies.

Finally, sadly, I report that the New Year's resolutions made last December didn't go far:

- I resolved to focus more on francophone writers, yet read just one: Philippe-Joseph Aubert de Gaspé (and then only in translation).

- I resolved to feature more non-fiction, and yet this writer of non-fiction reviewed nothing but fiction.

- I resolved to keep kicking against the pricks. This was easily done. Witnessing the miscreants of the Freedom Convoy roll past on its way to Ottawa gave extra incentive.

Here's to the New Year!

Bonne année!

The Very Best Reads of the Second Plague Year (2021)

The Very Best Reads of a Plague Year (2020)

The Very Best Reads of a Very Strange Year (2019)

Best Books of 2018 (none of which are from 2018)

The Year's Best Books in Review - A.D. 2017

The Year's Best Books in Review - A.D. 2016

The Year's Best Books in Review - A.D. 2015

The Christmas Offering of Books - 1914 and 2014

A Last Minute Gift Slogan, "Give Books" (2013)

Grumbles About Gumble & Praise for Stark House (2012)

The Highest Compliments of the Season (2011)

A 75-Year-Old Virgin and Others I Acquired (2010)

Books are Best (2009)