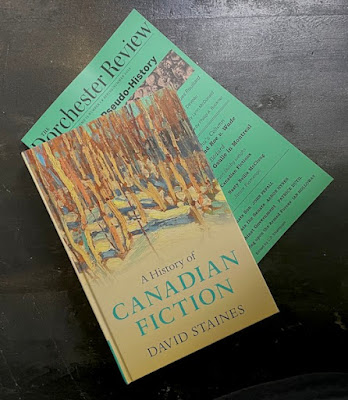

Several months ago, The Dorchester Review asked me to review David Staines' A History of Canadian Fiction.

Who am I to turn down an invitation.

Professor Staines' book was read at great sacrifice. Going through its 304 pages I ignored Stephen Henighan, a favourite critic, who shared his opinion of A History of Canadian Fiction in the pages of the Times Literary Supplement. A blind eye was turned to Stephen W. Beattie, another favourite, who reviewed the book for the Quill & Quire.

After submitting my review I read the two Stephens, sat back, and watched for more. I was more than rewarded with John Metcalf's newly published The Worst Truth: Regarding A History of Canadian Fiction by David Staines (Windsor: Biblioasis, 2022).

He provides a useful introduction to Inuit literary culture, paying the 39,000 native speakers of Inuktituk an attention he denies to Canada's 7.3 million native speakers of French.

How is it that a book titled A History of Canadian Fiction would exclude work written in French? Remarkably, Staines does not address this issue. In fact, he doesn’t so much as recognize the existence of Canadian fiction written in French. Of the hundreds of writers of fiction named in this book, we find two French names: Roger Lemelin and Gabrielle Roy. They first feature in a short list of “important people” who were once interviewed by Mavis Gallant and reappear as in another list of writers whose fiction Mordecai Richler had read. Roy’s name is in a third list, this of writers with whom Sandra Birdsell corresponded.

And that’s it.

The only mention of a work written in French appears in a nine-page "Chronology of historical, cultural, and literary events" that precedes the text itself. Next to the year 1632, we find: “Jesuit Relations, an annual, begins and continues until 1673.” But of course, they weren’t the “Jesuit Relations,” they were the Relations des jésuites.

And I have even more to say.

Invitations accepted.

Go ahead, Brian: consider this an invitation to say more.

ReplyDeleteThank you, Debbie.

DeleteThere were several things I might've added, one of which concerned John Metcalf himself. Early in the seventh chapter - " Canada's Second Century" - we find this: "In late 1970, John Metcalf (b. 1938) organized a group of men. Hugh Hood (1928-2000), Clark Blaise (b. 1940), Ray Smith (1941-2019), and Raymond Fraser (1941-2018)." Metcalf, "British-born and raised," is described as a man who wrote "Waugh-like tales." No mention is made of his decades as a critic, or his work as an editor at Porcupine's Quill and Biblioasis.

Of the five Storytellers, Staines tells of two who "deserve attention:" Smith and Blaise. This dismissal of Metcalf in odd, but then Staines mentions no editors in his book.

The final chapter, "Canadian Fiction in the Twenty-First Century" - races through the lives and works of twenty writers, many of whom Metcalf edited and mentored.

Are all so deserving of recognition as, say Grant Allan (not mentioned by Staines), Robert Barr (ditto), Margaret Millar (ditto), Ross Macdonald (ditto), William Gibson (ditto) or John Metcalf?

I suggest not.

My question, not surprisingly, is: how well are women authors represented? although I suspect I know the answer.

DeleteAnon, Prof Staines profiles the works of sixty women and seventy-six men. Figures don't tell the whole story, of course. For example, he devotes more attention to Margaret Atwood - seven of 293 pages - than any other writer. Gilbert Parker receives a paragraph.

DeleteThe second longest chapter, titled "The Second Feminist Wave," is devoted to Atwood, Adele Wiseman, Margaret Laurence, Audrey Thomas, Marian Engel, and Alice Munro. In doing so, they are set apart from the book's longest chapter, "The Second Canadian Century," in which author's who emerged in the 'fifties, 'sixties, and 'seventies is discussed. This was a mistake, I think.