Mrs Annie G. Savigny

Toronto: William Briggs, 1888

229 pages

Toronto: William Briggs, 1888

229 pages

The first chapter, 'Toronto a Fair Matron,' begins:

Two gentlemen friends saunter arm in arm up and down the deck of the palace steamer Chicora as she enters our beautiful Lake Ontario from the picturesque Niagara River, on a perfect day in delightful September, when the blue canopy of the heavens seems so far away, one wonders that the mirrored surface of the lake can reflect its color.

Dale and Buckingham are the two gentlemen friends. In their sauntering, the former teases the latter for being a bachelor. Dale brags that he has not only wed, but has managed to father a child, whilst friend Buckingham prefers the company of his gentleman's club.

I describe this opening scene because it suggests an intriguing read.

Sadly, A Romance of Toronto is not.

Buckingham has joined Dale, Mrs Dale, their child, and pretty governess Miss Crew on a voyage from New York to Toronto. His presence aboard the Chicora is something of a mystery, but then the same might be said of the Dales and young Miss Crew. All may or may not involve a certain Mrs Gower, who has put to pen "a letter descriptive of Toronto." Dale reads it aloud as the palace steamer approaches Ontario's capitol. Four pages are consumed, these being the middle two:

|

| Cliquez pour agrandir. |

A Romance of Toronto is not a long novel but it demands a good amount of time and a great deal of concentration and patience. The reader may feel lost in the early chapters, but will eventually come upon a path. That same path will split in two, and then come together in the final pages.

In her introductory note, Mrs Savigny describes A Romance of Toronto as a novel consisting of two plots.

Dale and Buckingham have nothing to do with either.

The first involves young Charles Babbington-Cole. He knows Mrs Gower through his father, Hugh Babbington-Cole. A widower in frail health, Babbington-Cole père was once engaged to a wealthy Englishwoman. Tragically, the union was prevented through conniving and lies told the bride-elect by the sister of his late wife. The Englishwoman instead married her guardian with whom she had a daughter. When the sister-in-law's malfeasance was exposed Hugh Babbington-Cole and the Englishwoman – identified only as "Pearl" – vow that their offspring will one day wed and together inherit her riches.

And so, Charles Babbington-Cole bids Mrs Gower adieu, embarking for England and a storyline that reads like a very bad imitation of May Agnes Fleming; kidnapping, false identity, forced marriage, and a gothic manor house will figure.

The second plot – much more absurd, yet somehow less interesting – concerns Mrs Gower herself. A woman who has has twice worn the black robes of widowhood, she is cornered into accepting a marriage proposal from Mr Cobbe, by far the most repellent of her social set. Mrs Gower tells Mrs Drew how this came to be in 'The Oath in the Tower of Toronto University,' the novel's sixteenth chapter. This is its beginning:

|

| Cliquez pour agrandir. |

Several more pages pass in Mrs Gower's telling, but it comes down to this: Cobbe, who has been pestering Mrs Gower to marry him, fools her into believing that they've become locked in the tower overnight. Fearing scandal, Mrs Gower promises to marry Cobbe if he can only find a way out of their situation. The two descend only to find that the tower door isn't locked, and yet she holds herself to the oath.

Nothing is spoiled in reporting that all ends happily; the first of the novel's two epigraphs suggests as much.

Mrs Savigny's note makes it plain that A Romance of Toronto (Founded on Fact) is a roman à clef. but who are its models? Her two plots – "one of which was told to me by an actor therein; the other I have myself watched" – are "living facts." Who are the originals?

A Montrealer, I hope to hear the answer from one of Toronto's fair children.

Mrs Savigny attributes her second epigraph – "What would the world do without story-books" – to Charles Dickens. I've not been able to find this quote or anything resembling it outside the pages of her novel.

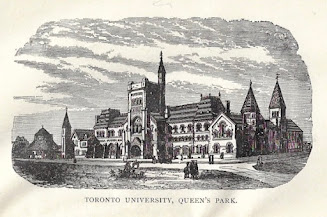

Trivia II: The University of Toronto is referred to only once as such; "Toronto University" is used throughout the rest of the novel. I asked Amy Lavender Harris, author of Imagining Toronto, about this. She suggests that "Toronto University" might have been used to connote familiarity.

Bloomers: There are two, both expressed by Mrs Gower. The first is upon learning of Charles Babbington-Cole's departure for England:

"Don't you think, Lilian, that the opposite sex is usually chosen to lend an ear?" she said, carelessly, to conceal a feeling of sadness at the out-going of her friend; for she is aware that the old friendly intercourse is broken, now that he has gone to his wedding.

In the second, Mrs Gower is speaking of the man she loves:

"I am so glad he has come into my life: I feel lonely at times; and he is so companionable, I know. What dependent creatures we are, after all—houses and lands, robes a la mode, even, don't suffice. Intercourse we must have."

Object and Access: A deceptively slim hardcover. Fifty years after publication, my copy was added to the library of the Department of the Secretary of State. One wonders why. Might it have something to do with the suggestion that A Romance of Toronto is a roman à clef? I'm guessing not, but like to imagine otherwise.

I don't know what to make of the binding, which is markedly different than Harvard University's copy:

I purchased A Romance of Toronto three years ago. As I write this just two copies are listed for sale online. The least expensive – $65 – is "good only." At $247, the alternative is "very fine." Take your pick.

A Romance of Toronto was reprinted in 1973 by the University of Toronto. If anything, that edition is even more rare. Long in the public domain, it continues to be picked over by print on demand vultures. This cover is my favourite by far:

A Romance of Toronto was reprinted in 1973 by the University of Toronto. If anything, that edition is even more rare. Long in the public domain, it continues to be picked over by print on demand vultures. This cover is my favourite by far:

Related post:

No comments:

Post a Comment