|

| The Calgary Herald, 9 December 1960 |

Showing posts with label MacLennan (Hugh). Show all posts

Showing posts with label MacLennan (Hugh). Show all posts

23 February 2014

12 November 2012

About Those Old New Canadian Library Intros (with some stuff on Martha Ostenso's Wild Geese)

Before I'm accused of being ungrateful, allow me this: The old New Canadian Library was good for this country. As a university student, I was happy to ignore its abridgements, poor production values and ill-advised selections. The introductions, however, were hard to stomach. I was then new to Canadian literature – we did not study such things Quebec's public schools – and yet could already see that many of the NCL intros were inept, inaccurate and factually incorrect.

Answers as to why so many were so flawed are found in New Canadian Library: The Ross-McClelland Years, 1952-1978, Janet Friskney's invaluable study of NCL's best days. The author tells us that founder Malcolm Ross was adamant that there be introductions, quoting: "I thought it would be useful even for teachers, many of whom were teaching Canadian books for the first time and who had never studied Canadian literature."

As Prof Friskney notes: "in many cases, an NCL introduction was one of the earliest, and sometimes the first piece of critical analysis to appear about a particular work."

Such a sad state of affairs. The blind led the blind... and yet things did improve. In 1962, Hugh MacLennan wrote Ross that the NCL was on its way to becoming "one of the most important things in Canadian publishing." He went on to praise the series for making available the previously unavailable and scarce, adding: "These, with the introductions, are building a true body of relationship between critic and author and the public."

Such a sad state of affairs. The blind led the blind... and yet things did improve. In 1962, Hugh MacLennan wrote Ross that the NCL was on its way to becoming "one of the most important things in Canadian publishing." He went on to praise the series for making available the previously unavailable and scarce, adding: "These, with the introductions, are building a true body of relationship between critic and author and the public."

(MacLennan's Barometer Rising had already found a place in the series, and would soon be joined by Each Man's Son.)

(MacLennan's Barometer Rising had already found a place in the series, and would soon be joined by Each Man's Son.)

All this brings me to Carlyle King's Introduction to Wild Geese, Martha Ostenso's big book, which I reread just yesterday. The intro first appeared when Wild Geese joined the NCL in 1961, and was reprinted until 1996, when it was replaced with an afterword by David Arnason.

Thirty-five years.

I first read these words from Prof King in 1986:

Where to begin? How about with that third sentence, in which King describes the literary landscape of 1923 Canada:

The truth about fraudster and faux-Swede Grove – German Felix Paul Greve – was revealed in 1971 through the sleuthing of D.O. Spettigue. While King cannot be faulted for his 1961 Introduction, one wonders that it continued to be used as the new millennium approached.

Carlyle King informs that Grove, Callaghan and Ostenso stand outside "the Sunshine School of Canadian fiction", in which "human nature is fundamentally noble and Rotarian morality always triumphs. The main characters are basically nice people. Nobody ever suffers long or gets really hurt or says "damn.'"

Oh, dear.

In 1923, the most recent of "Louisa [sic] M. Montgomery's long series of 'Anne' books" was Rilla of Ingleside (1921). A novel set during the Great War, it sees one of our dear Anne's sons taken prisoner by the Hun as another is slaughtered on the battlefield. It's true that the latter is "killed instantly by a bullet during a charge at Courcelette", but I'm not at all convinced this is what King meant in writing that nobody ever suffers long.

Can we at least agree that in this case a character "really gets hurt"?

A good many characters are killed in Ralph Connor's The Sky Pilot in No Man's Land – some suffering long before they die.

And "damn"?

There's a whole lotta cussin' goin' on in the novel, much of which comes from the sky pilot himself:

Yes, there's venereal disease, too.

Is it any wonder that no reference to "the Sunshine School of Canadian fiction" is found outside Carlyle King's writings?

As Prof Friskney notes: "in many cases, an NCL introduction was one of the earliest, and sometimes the first piece of critical analysis to appear about a particular work."

Such a sad state of affairs. The blind led the blind... and yet things did improve. In 1962, Hugh MacLennan wrote Ross that the NCL was on its way to becoming "one of the most important things in Canadian publishing." He went on to praise the series for making available the previously unavailable and scarce, adding: "These, with the introductions, are building a true body of relationship between critic and author and the public."

Such a sad state of affairs. The blind led the blind... and yet things did improve. In 1962, Hugh MacLennan wrote Ross that the NCL was on its way to becoming "one of the most important things in Canadian publishing." He went on to praise the series for making available the previously unavailable and scarce, adding: "These, with the introductions, are building a true body of relationship between critic and author and the public." (MacLennan's Barometer Rising had already found a place in the series, and would soon be joined by Each Man's Son.)

(MacLennan's Barometer Rising had already found a place in the series, and would soon be joined by Each Man's Son.)All this brings me to Carlyle King's Introduction to Wild Geese, Martha Ostenso's big book, which I reread just yesterday. The intro first appeared when Wild Geese joined the NCL in 1961, and was reprinted until 1996, when it was replaced with an afterword by David Arnason.

Thirty-five years.

I first read these words from Prof King in 1986:

Where to begin? How about with that third sentence, in which King describes the literary landscape of 1923 Canada:

Callaghan was on the Left Bank in Paris among the American expatriates, trying his hand at stories for the little magazines of experimental writing...No, Morley Callaghan was then studying law at the University of Toronto. It was in 1929 that Callaghan first visited the Left Bank, by which time he was a published author comfortably installed within Charles Scribner's stable.

...Grove, who had written for twenty years in the intervals of an itinerant farm-hand's existence, did not get a first novel into print until 1925.It was in 1905 that Frederick Philip Grove – or, as King seems to prefer, "Philip Grove" – published his first novel. The "itinerant farm hand's existence" included a stretch in Austrian prison, bohemian living in Berlin and Paris, drinks with Andre Gide and H.G. Wells... and I won't go into his crossdressing wife with the birdcage bustle.

The truth about fraudster and faux-Swede Grove – German Felix Paul Greve – was revealed in 1971 through the sleuthing of D.O. Spettigue. While King cannot be faulted for his 1961 Introduction, one wonders that it continued to be used as the new millennium approached.

Carlyle King informs that Grove, Callaghan and Ostenso stand outside "the Sunshine School of Canadian fiction", in which "human nature is fundamentally noble and Rotarian morality always triumphs. The main characters are basically nice people. Nobody ever suffers long or gets really hurt or says "damn.'"

Oh, dear.

In 1923, the most recent of "Louisa [sic] M. Montgomery's long series of 'Anne' books" was Rilla of Ingleside (1921). A novel set during the Great War, it sees one of our dear Anne's sons taken prisoner by the Hun as another is slaughtered on the battlefield. It's true that the latter is "killed instantly by a bullet during a charge at Courcelette", but I'm not at all convinced this is what King meant in writing that nobody ever suffers long.

Can we at least agree that in this case a character "really gets hurt"?

A good many characters are killed in Ralph Connor's The Sky Pilot in No Man's Land – some suffering long before they die.

And "damn"?

There's a whole lotta cussin' goin' on in the novel, much of which comes from the sky pilot himself:

Yes, there's venereal disease, too.

Is it any wonder that no reference to "the Sunshine School of Canadian fiction" is found outside Carlyle King's writings?

Related post:

21 October 2012

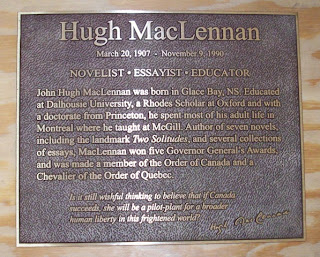

Hugh MacLennan Memorial Plaque

This coming Friday, 26 October, will see the dedication of a plaque in memory of Hugh MacLennan at the Writers' Chapel of Montreal's St James the Apostle Anglican Church.

All are welcome.

Friday, 26 October 2012

6 p.m.

Church of St James the Apostle

1439 St Catherine Street West, Montreal (Bishop Street entrance)

Labels:

MacLennan (Hugh),

Plaques,

Writers' Chapel

27 February 2012

Freedom to Read Week: Episode

"A remarkable first novel about madness – its feelings, treatment and powers."

— Books of the Month

"Filth and muck."

On 17 February 1956, a bitterly cold day in Ottawa, the American News Company was found guilty of having in its possession for the purpose of distribution "obscene written matter, to wit: 117 copies of a book entitled 'Episode', written by Peter W. Denzer."— Raoul Mercier, K.C.

The distributor was fined $5000 ($42,500 today), roughly $43 ($356) for each and every copy of the 25¢ paperback. This absurd amount would be described in The Canadian Bar Review as "by far and away the heaviest penalty imposed for an offence of this nature in Ontario, and probably Canada." Meanwhile, Crown prosecutor Raoul Mercier, the future Attorney General of Ontario, was clicking his heels.

The Vancouver Sun, 18 February 1956

Peter Denzer died earlier the month at the age of ninety; his friend Peter Anastas paid tribute with a very fine obituary. It's important to note, I think, that the author of Episode, a novel about a man's struggle with mental illness, had himself suffered. What's more, Peter Denzer had been an early defender and sympathetic champion of those struggling with mental health disorders.

Episode is, I suppose, somewhat autobiographical. Hugh MacLennan was an admirer of the novel. His biographer, Elspeth Cameron, describes it as a precursor to One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. I've yet to come across a negative review. Everything I've read about Episode indicates that it is both fascinating and important. And yet, Canadians who want to read Episode are out of luck. You see, while Episode, can be found in libraries throughout the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia, not a single Canadian library – public or academic – has a copy.

Those looking to place blame need only look to this little, little man:

Raoul Mercier

1897-1967

11 January 2011

The Solid Walls of St James the Apostle

A very fine column by Mike Boone on St James the Apostle's Writers' Chapel from yesterday's Gazette:

City's Great Writers Honoured in Historic Church

How true.

09 November 2010

Acknowledging Hugh MacLennan

Hugh MacLennan died twenty years ago today. I never met the man, though I did once nod reverently as we passed each other in an otherwise deserted university hallway. He smiled. I should have stopped. I've since learned not to let such opportunities slip by.

Another regret: I've never seen the screen adaptation of MacLennan's Two Solitudes. When offered the opportunity I chose Superman: The Movie. Christopher Reeve as the Man of Steel beat Stacy Keach's Huntly McQueen. This happened back in 1978 when I was still a young pup – shouldn't I be given a second chance? As far as I can tell, Two Solitudes never made it to Beta or VHS or LaserDisc or DVD. YouTube doesn't have so much as the trailer.

Is it any good? All I have to go on is the poster, a publicity photo, Macmillan's movie edition and a handful of contemporary reviews. It seems no one was particularly crazy about the film... "letdown" is the most accurate one-word summation, though Jay Scott provided a particularly detailed and damning review for the 30 September 1978 Globe and Mail:

Stylistically, Two Solitudes is pure Hollywood, Old Hollywood. It is not enough that we make exploitation films for the Americans: now we are copying their ponderous historical dramatizations, employing composer Maurice Jarre, the once-favored treacly symphonizer of those lumpen ethics. It is a characteristically Canadian irony that the dramatizations being Xeroxed no longer exist in their original form. Two Solitudes does not resemble any contemporary American film of quality as much as it resembles made-for-TV novels like Washington: Behind Closed Doors and Rich Man, Poor Man; it's a passionless political soap opera.

A few months later, Scott named Two Solitudes as one of ten worst films of 1978, while pointing to Superman was one the ten best.

Wonder if I'd agree.

Labels:

Criticism,

Film,

Globe and Mail,

MacLennan (Hugh),

Macmillan of Canada,

Novels,

Scott (Jay)

06 February 2010

Ex Libris: Hugo McPherson

Nothing at all remarkable about the inscription here to critic Hugo McPherson, interest is to be found in the book itself. Nearly half a century after publication, Das Romanwerk Hugh MacLennans still ranks as one of a very few foreign language works of criticism devoted to a Canadian author. Its existence reflects the once great spread of MacLennan's work outside the English speaking world. His novels were translated into French, Japanese, Korean, Norwegian, Swedish, Estonian, Czech, Romanian, Polish and German. In Hugh MacLennan: A Writer's Life (University of Toronto, 1981), biographer Elspeth Cameron writes that between 1963 and 1969 the German language edition of Barometer Rising sold over 100,000 copies.

I venture to say that not one of these translations is in print today. Here, in his home and native land, the fall of MacLennan's star has been even more dramatic. Two of his seven novels are out of print, as are every one of his collections of essays. I'd like to think that a revival is on the horizon. In Canadian letters there are so few second acts.

03 February 2010

Ex Libris: Hugh MacLennan

In 1991, six or so months after his death, Hugh MacLennan's personal library was put up for sale through Montreal's Word bookstore. It wasn't exactly a pretty sight. MacLennan treated his books badly, and it was clear that he cared not one whit about fine editions. Looking through the battered volumes made me respect the man all the more. Here was someone who cared for the word, not the vessel. He'd read and reread with great appetite, while I'd worried over sunlight and fragile spines.

I bought a dozen of these worn volumes, including a presentation copy of Alistair MacLeod's As Birds Bring Forth the Sun and Other Stories and an old 95¢ Signet Classics edition of Robinson Crusoe (my cost: $1.95). All were books I'd been wanting to read for some time, with the exception of The Conscience of the Rich. C.P. Snow's name meant little to me then, but I was amused and intrigued by MacLennan's critique.

Related post:

Labels:

MacLennan (Hugh),

Novels

25 October 2009

White Circle Canadians (w/ Warning)

In 1943 and 1944, Collins placed some pretty pricey White Circle adverts in the Globe and Mail. I expect these spurred sales, but they appear to have had no effect on editorial – during those same years, there was otherwise no mention of the imprint in the paper. This is known as integrity. Indeed, the "Canadian Classic" piece featured in Thursday's post marks one the very few times White Circle appeared in actual copy. If the somewhat unreliable Globe and Mail search engine is to be trusted, the imprint was last mentioned in its 1 April 1950 edition – and then only in connection with rising star Hugh Garner:

Not much of a notice, but interesting in that Cabbagetown, which White Circle would publish, is the only mass market paperback original found in the Canadian canon. (Should I be counting Neuromancer?) The piece also reflects a significant difference between White Circle and its Canadian competitors. Harlequin's most acclaimed Canadian writer was Thomas H. Raddall, News Stand Library had... well, Al Palmer, but White Circle published Garner, Stephen Leacock, Hugh MacLennan, Earle Birney, Ralph Connor and Roderick Haig-Brown.

(In fairness to News Stand Library, it did publish Garner's pseudonymous 1950 "Novel about the Abortion Racket", Waste No Tears.)

Six decades later, Garner has dimmed, Connor is little read, and Haig-Brown seems relegated to regional writer status – but Leacock, MacLennan and Birney continue to be celebrated and studied.

In keeping with this month of Thanksgiving, what follows is a final visual feast featuring some of White Circle's more interesting Canadian titles. The pitch on the early Barometer Rising is a favourite. "AS EXCITING A NOVEL AS MAY SAFELY BE PUBLISHED", it begins, immediately contradicting itself with this warning: "A NOVEL OF LITERALLY UNENDURABLE SUSPENSE".

There you have it: not safe at all, but literature's equivalent of Ernest Scribbler's killing joke.

1943 and 1951

1945

1952

My thanks to JC Byers, whose thorough Bibliography of Collins White Circle provided images of titles missing in my own collection.

12 July 2009

MacLennan Rising

Belated recognition of the new McGill-Queen's University Press edition of Hugh MacLennan's The Watch That Ends the Night, the first in its reissue of novels by the 'seminal Canadian writer'. A couple of decades ago it would've been inconceivable that a MacLennan novel could go out of print. Not so in today's unhealthy environment – even this, the author's finest work of fiction, had been unavailable for several years.

I know of seven other cover treatments of the novel, but this new one by David Drummond's has become my favourite. The designer discusses the series in his blog.

Two other favourites follow.

Macmillan of Canada first edition, 1959

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)