The Story without a Name

Arthur Stringer and Russell Holman

New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1924

The story without a name is not nearly as important as its title. Any old story would've done. It's pure product, born of Hollywood, conceived as a gimmick: release a film "without a name" and offer cash for title suggestions.

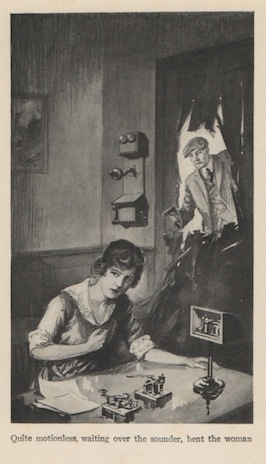

How closely the novel matches the product is anyone's guess; it's a lost film. And because it's a lost film, I'll be posting all eight stills featured in the book. And because you're unlikely to read the novel – there's no reason why you should – I'll be sketching out the plot from beginning to end.

This is the second Stringer I've read this year to feature a car crash. In the first,

The Wine of Life (1921), a spurned lover sends his auto flying off an embankment into Lake Erie. The incident in this novel produces a much happier result, bringing about the meeting of Mary Walsworth and garage mechanic Alan Holt.

"Fresh and fragrant as apple-blossoms in cool summer white", Mary happens to be the daughter of Admiral Charles Pinckney Walsworth, head of the Naval Consulting Board in Washington, DC. Quite a coincidence this, as Alan is working on an invention he hopes to present before the selfsame board: "a device for triangulating radio rays, concentrating them into a single ray of such tremendous force that it would sink ships and set fire to cities."

Admiral Walsworth is unimpressed. "I've had exactly twenty 'death-ray' inventions offered me in the last seven months," he grumbles. "None of them is worth anything. The thing is simply impossible.

And stay away from my daughter!"

That last bit in italics is mine; it doesn't appear in the book, though it could have.

Oh, Alan seems a nice enough fellow, and he has been awfully helpful, but Walsworth would remind Mary that he's "a garage-employee in a country ex-blacksmith shop". The admiral cares not one wit that the lad served in his Navy during the Great War, and ignores the fact that Alan's prototype actually works. The rest of the Consulting Board isn't so prejudiced, and offers the young inventor funds to perfect "the most important invention since wireless had been discovered".

Would that security had also been offered.

As Alan works on his death ray device, dark forces gather. Walsworth falls under the spell of a

femme fatale, a mysterious tramp wanders outside the grounds and two thugs pose as government agents. All are in the employ of international criminal mastermind Mark Drakma, who intends to sell Alan's invention to a foreign power.

Mary is kidnapped, bound, and thrown into the tonneau of a touring car. Alan too is kidnapped, but as bondage plays a lesser part he's afforded numerous opportunities for escape. One involves an aeroplane!

Sadly, our hero fails at every turn. He and Mary are reunited on a ship somewhere in the Atlantic, where Drakma demands Alan make him a death ray device. If he refuses?

"I've some choice specimens in my working crews off the islands. You'd rather see her thrown into a cage of tigers, I fancy, than passed on to one of those gangs of rum-swilling cutthroats. But as sure as you're standing there I'll put her aboard the foulest schooner I own and leave her there until even you wouldn't want her!"

Drakma's words fire the inventor's imagination:

The helpless youth raised his stricken eyes to the face of the woman he loved. In that face he saw pride and purity. She impressed him as something flower-like and fragile, something to be sheltered and cherished and kept inviolate, something to die for, if need be, before gross hands should reach grossly for her.

Alan agrees to master criminal's terms, but is overturned by Mary, who gives a rousing speech about love of country. A real trooper, she displays great optimism in the face of grossly groping hands:

"It can't be for long, Alan," broke in the girl, her head poised high and her hands clenched hard as she was seized and thrust toward the rail-opening. "And we're doing it for the flag, dear, that men like this daren't even fly!"

Alan is dumped on a remote cay and is told that he'd better get to building that death ray device if he wants to keep Mary inviolate. The flaw in this plan will later be made evident when Alan builds the thing, then uses it to down one of Drakma's aeroplanes.

Now, to be fair to the criminal mastermind, it could be that he expected the cay's other two residents, Don Potter and his "

spiggoty" lady friend Dolores to keep a watch on the young inventor.

Potter stands out as the lone character with a bit of flesh on his bones. A bitter and bloated Harvard man, he served valiantly during the Great War, only to be betrayed by his country. "Come back and found they'd taken my liquor away from me", he tells Alan. Short years later, Potter's in charge of Drakma's rum-running distribution centre. Just the occupation for a boozehound.

The shadow of the Great War hangs over this novel. Alan had secured his widowed Quaker mother's blessing to fight overseas by selling the conflict as the War to End All Wars. He couldn't have been more wrong, of course, which must have made dinner conversation about his death ray all the more difficult.

"Once I've got it into shape," he outlined his intentions to her, "I'll offer it to the Navy. If they take it, this country will be placed in a position where the rest of the world will be afraid of us. And the United States will be able to prevent wars between other nations simply by threatening to jump in with the death ray and burn the offenders off the face of the earth."

I wasn't at all convinced.

Being a drunk, Potter never notices the crashed plane, nor does he glom onto the fact that his prisoner is building a raft at the other end of the cay. Alan escapes, taking the death ray device with him. He makes for the foul schooner on which Mary is being held captive, and is quickly overpowered by rum-swilling cutthroats.

If only he'd thought to use his death ray device.

A fire breaks out, as fires do in adventure stories. In the ensuing confusion, Alan and Mary escape on the raft. Drakma's ship gives chase until the US Navy shows up and kills all the crooks.

Again, death rays do not figure.

This brings me to one of the most disappointing and mysterious aspects of the novel. For reasons perhaps known only to Stringer, Holman and Paramount Pictures, Alan never uses his death ray device when in danger. Only once, when downing the aeroplane, does he aim it at the enemy. Other than that it's used to pierce a hole in a small metal plate, destroy a fresh tub of ice cream and give an innocent, unsuspecting old man a series of heart attacks…

You know, maybe Alan isn't such so nice after all. What kind of guy wastes ice cream?

The book disappoints further in that not one of the images from the film shows Alan's death ray device. Tech geeks have to settle for actors staring at a radio.

Another novel that ends in a wedding, I'm afraid. Stringer and Holman forget about the Holts' Quakerism by holding the happy event in "the little elm-shaded church in Latham where Alan and his mother had always worshiped." One sentence begins, "As the old clergyman droned…" I nearly gave up at that point, but stuck it out.

There was less than a page to go.

A Bonus:

|

| Mary, Alan and the death ray device (Photoplay, July 1924) |

Bloomer:

"She nearly cost us your 'death-ray' machine and she tried to lead me to an ambush at Drakma's that might have cost me my honor, if not my life. She made love to me with one hand, so to speak, while she attempted to pick my pocket with the other."

Trivia I: The winning suggestion,

Without Warning, was announced in the January 1925 issue of

Photoplay. Both film and novel were rereleased under this title.

Trivia II: Unreliable and unstable science fiction author

F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre claimed to have seen

The Story without a Name. His captious review features in

the film's IMDb entry.

Trivia III: Forgotten film stars Antonio Mareno and Agnes Ayres were cast as Alan and Mary. The villain Drakma was played by Tyrone Power, father of the more famous Tyrone Power. The senior Power died – quite literally in his son's arms – while filming the 1932 remake of

The Miracle Man, based on the novel by Montrealer Frank L. Packard.

Object: A 312-page hardcover supplemented by eight plates depicting scenes from the Paramount Pictures picture. I purchased by copy in April from a bookseller in western New York. Price: US$15. Is it a first? One never really knows with Grosset & Dunlap. I've seen a red-boarded variant.

Access: Though not plentiful, copies of

The Story without a Name begin at the low price of US$10. Copies with dust jackets – there are three – can be had for as little as US$60.

Copies of

Without Warning are less common. That said, all four currently listed online have their dust jackets. Strange but true. Prices range from US$60 to US$85. Condition is a factor.

A warning about

Without Warning: This edition features only four of the plates featured in

The Story without a Name.

Twelve of our academic libraries hold copies, as do public libraries serving the residents of Toronto and London.

Related post: