|

| Death About Face Frank Kane Toronto: Harlequin, 1951 |

Related posts:

A JOURNEY THROUGH CANADA'S FORGOTTEN, NEGLECTED AND SUPPRESSED WRITING

|

| Death About Face Frank Kane Toronto: Harlequin, 1951 |

A Scottish transplant by way of the United States, Bertrand W. Sinclair wasn’t Canada’s most prolific pulp magazine writer; I know of two hundred and ninety-four appearances, which is nowhere near the fifteen hundred or so (I lost count) logged by Ontarian H. Bedford-Jones. Sinclair isn’t our best-known pulp writer, either; that title belongs to Thomas P. Kelley, author of The Black Donnellys, Vengeance of the Donnellys, I Found Cleopatra, and, of course, The Gorilla’s Daughter.

Sinclair’s distinction rests in being our best pulp writer. Though his plots are invariably marred by melodrama — a prerequisite in pulps — he usually brought something to his stories that shook convention. My favourite Sinclair novel is The Hidden Places. Serialized in The Popular Magazine (Oct 7 - Nov 20, 1921), it concerns a disfigured war veteran who seeks sanctuary on the remote BC coast from Vancouverites disgusted by his appearance. By great coincidence, he finds his nearest neighbour is his wife, who believes he'd died in battle. She is now married to another man.

As I say, melodrama.So begins my latest Dusty Bookcase review, posted today on the Canadian Notes & Queries website. Here's the link.

|

| La femme de sa mort [Vanish in an Instant] Paris, Presses de la Cité |

|

| Mortellement votre [Beast in View] Paris: Presses de la Cité, 1957 |

|

| Un air qui tue [An Air That Kills] Paris: Presses de la cité, 1958 |

|

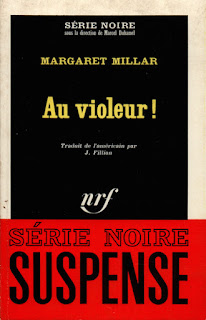

| Au violeur! [The Fiend] Paris: Gallimard,1966 |

We had a very Canadian eagerness to make something of ourselves.The cover of this most recent volume in Syndicate Books' Collected Millar suggests that Paul Prye was the author's first detective, when the distinction really belongs to William Bailey. The novel opens with his sister, Amanda, being awoken in the wee hours by a disturbing phone call. A woman named Eve Hays has found a dead man in her stairwell – heart failure, she thinks. An indignant Miss Bailey suggests that a call an undertaker, and not the Inspector of the Mertonville, Illinois, police department, would've been more appropriate. A few minutes later, Miss Hays phones back to apologize for her little joke, confessing that she'd had too much to drink.

— Kenneth Millar, 1971

"You are a physician?"

"Well, more or – Yes, I am. But my practice for the last ten years has been in the field of mental abnormalities: neurology, psychoneurology, abnormal psychology, psychoanalysis. I'd rather be called a quack, however. It puts people at ease."

"But you have a medical license?"

"A medical license, a dog license, a driver's license. I even bought a marriage –.

"You are whimsical, I see," the inspector said dryly.

"Yes, indeed.

"The angel that provided o'er my birth

Said, 'Little creature formed of joy and mirth...'

So you see how I stand."I like Blake as much as the next guy – perhaps more – but Prye's habit of quoting the great man irritated. The humour, lighter and less sophisticated than in Millar's other novels, infects the dialogue, as in this interview between Bailey and the Hays family butler:

"Name, please," he said sternly.An upstanding man with little time for nonsense, Bailey initially seems the very model of what one would want in a detective. However, as things progress, we come to recognize serious lapses in judgement, the most obvious being his acceptance of Prye's intrusion in the investigation. Bailey's biggest mistake is to place those living in the Hays' residence under something resembling house arrest. Ignoring the legality of the edict – Millar does – this doesn't prove in the least bit effective; in fact, the body count increases as a result. One character collapses from a poisoned digestif, while another is found dead in the kitchen pantry.

"Joseph Butler."

"Joseph Butler?"

"Joseph Butler," Joseph repeated firmly.

"Sure, it's possible, Chief," Sergeant Abbott said eagerly. "I knew a broad once who was called Broad!"

"A most striking analogy, Sergeant, but this is hardly the time for amorous reminiscences." Bailey turned to Joseph. "Now, Joseph, I'd like to point out to you that it is your duty to lay whatever information you may have before the police, even though it may seem to be damaging to your employers. I appreciate your loyalty but I must have truth."

Mr. Thomas Philips smiled happily. Not every man can afford to retire at the age of forty-five; in fact, not every man in Mr. Philips's business lived to that age, The mortality rate in certain professions tends to be high, and Mr, Philips was planning an extended trip to South America.Before The Invisible Worm, the earliest Millar I'd read was Wall of Eyes (1943). A remarkable novel, written with a sure hand, it could have been included in the Collected Millar volume that Syndicate titled The Master at Her Zenith.

There was nothing of malice in his smile. He intended to retire gracefully. Old grudges were forgotten, and the past was a lucrative, even a pleasant, memory.

He made an excited little gesture with his hands. He was going away and he was never coming back, and it was rather nice to be saying good-by to someone. Tomorrow, Mr. Philips explained, he and Dolly would be on their way, perhaps on the water by this time. It was very late, and he was tired. He scarcely felt the pinprick on his neck, and by the time the hand closed over his mouth it was too late to do anything about it.

The pinprick and the hand... South America.... Dolly... and Mr. Philips's heart stopped beating.